Tackling the pandemic by geospatial mapping

One of the unnerving things about Covid-19—and there are many—is a lack of definitive information even after the passing of four months of the pandemic. As all humanity remains vulnerable to the deadly onslaught of this insidious virus, we would like to know how the virus progresses (and regresses) in a location, what is the rate of its spread, what conditions may slow down its rate, and what a comparison between different locations can suggest. In most cases, we do not have adequate answers.

Knowing that there will be no vaccination and adequate therapeutic support for another 12-18 months, all of us are anxious for any positive information. Scientists, medical professionals, politicians, statisticians and analysts are still scrambling to find some reassuring news regarding the vulnerability of the virus, and a way out of this pandemic.

There have been some hopeful claims regarding the impact of the coronavirus as far as Bangladesh is concerned. In a paper jointly funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, published on March 9 by Social Science Research Network (SSRN), authors from two Chinese universities stated that high temperature and high humidity reduce the transmission of Covid-19. The authors found that the arrival of the summer and rainy season in the northern hemisphere could effectively reduce transmission. In another paper posted on SSRN, and much publicised in the US, a group of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) claimed on March 19 that 90 percent of Covid-19 transmissions had occurred in regions that had temperatures between 3 and 17 degrees Celsius and absolute humidity between 4 and 9 grams per cubic metre during the outbreak.

On March 28, a group of researchers from the New York Institute of Technology stated that the countries without universal policies of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination (preventive measures to tuberculosis), such as Italy, Netherlands and the US, have been more severely affected compared to countries with universal and long-standing BCG policies. While WHO does not confirm a relationship between BCG vaccination and Covid-19 outbreak or transmission, the correlation between the virus and BCG histories remains an open topic.

The relatively low number of cases and deaths in Bangladesh and India, considering the population density and lack of sufficient precautions, may be attributed to either temperature or BCG, or both. But such claims have to be treated carefully as there are exceptions to each one of them. There are warm places like Brazil and Ecuador with a high number of cases and deaths.

Geospatial mapping has become a crucial tool for a data based verification of such claims or projections, and a comparative understanding of the impact of the virus. Mapping is an essential—and primary medium—for tackling any disastrous situation such as health crisis, natural calamity, war, etc. Perhaps the first health-based mapping began when John Snow produced hand-drawn paper maps of cholera cases during the cholera outbreak in Soho, London in 1854. In the current context of the pandemic, there are now more advanced methods of mapping aligned with new technologies. South Korea is an example. Being the second-worst affected country after China at the beginning of the global outbreak, the East Asian nation was successful in taking control of the situation without even enforcing a lockdown. Having the finest geo-information researchers, South Korea tackled Covid-19 by practicing and implementing artificial intelligence in mapping people's movement. Needless to say, such practices have also raised legitimate controversies.

Facebook recently launched its new interactive map that displays reported county-by-county Covid-19 symptoms from users across the US. While the initiative may help local governments better understand where to allocate resources and, eventually, when it is safe to start reopening from lockdown, the issue of infringing on individual privacy remains a serious matter.

There are other critical information that a global mapping can reveal, especially with air travel and the transmission of the virus. In a paper for the National Academy of Sciences of USA on March 13, a group of multidisciplinary researchers showed that international flights brought a total number of 566 Covid-19 cases to 26 countries within two months since the outbreak was first reported on December 31, 2019.

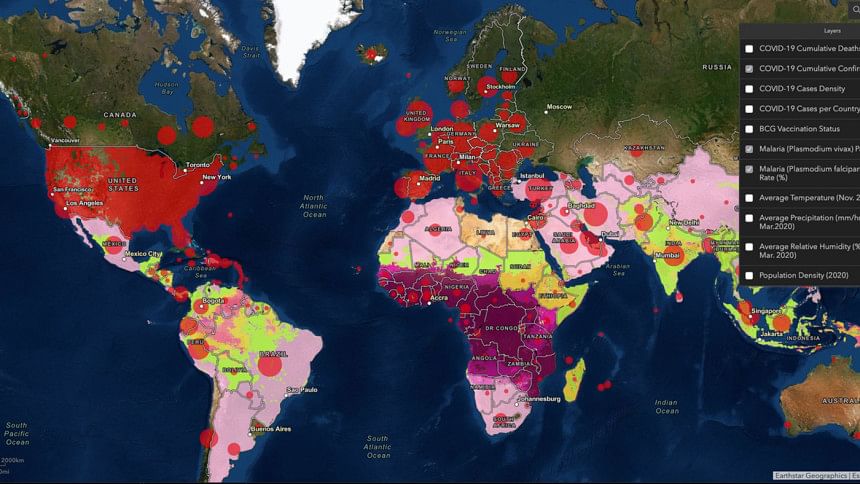

Launched on January 22, the real-time Covid-19 tracking map by Johns Hopkins University (JHU) in USA introduced a new dimension (real-time visualisation) of spatial science in the field of applied health geography. This tracking initiative has become the most cited source of Covid-19 spatial data for many scientific institutions, government officials, public health scholars and mainstream media. Ingesting big data from their sources, JHU uses this web-based geographic information systems (GIS) platform to report confirmed cases associated with some other statistical representations across the world in an interactive and near-real-time dashboard.

By making such information public, people can engage in hypotheses and conclusions on their own but based on facts. What if we could take the environmental and epidemiological parameters and correlate with Covid-19 cases in an interactive and evidential way? To effectively "flatten the curve," as this new phrase enters our thinking and planning, we need geo-information. As we are in a global pandemic situation, we need to work with a global spatial platform.

In response to the need of a geospatial data bank, researchers at Bengal Institute have created a unique online dashboard titled "An Atlas of Covid-19," in which global information of the virus, and associated parameters, are presented in a correlative way. First published on April 8, the dashboard has been attracting wide responses from all over the world. All critical criteria—from temperature to BCG vaccination—are overlaid on the global map. A comparative data on South Asian countries is also presented. Bengal Institute plans to add more relevant data and geographic and social information to the dashboard with a hope that the atlas may be helpful for strategising in mitigating this pandemic.

For dealing with the impact of Covid-19 and future public health crises, a better integration of digital infrastructure associated with geo-spatial mapping and data collating should be a priority in our country. A Covid-19 tracking platform was very much needed for Bangladesh but now, thanks to the State Minister for ICT Division, a platform has been launched on April 20.

Geospatial information and analysis confirm that a collaborative way of research among policymakers, doctors, public health researchers, data scientists, geospatial researchers and other experts is very much needed in tackling the unprecedented crisis we are in today.

The Bengal Institute dashboard may be accessed at: https://bengal.institute/covid19/ and the Covid-19 tracking platform can be accessed through http://covid19tracker.gov.bd/. In addition to the Atlas of Coronavirus, Bengal Institute also publishes Covid-19 Dhaka neighbourhoods and Bangladesh district case rates on a daily basis following IEDCR data at http://bit.ly/COVIDhaka and http://bit.ly/COVID19bd.

Mohammad Arfar Razi and Sanjoy Roy are geographers and geospatial experts, and direct the geographic unit at Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments