Tea advertisements and the ideal woman in 20th-century colonial Bengal

Tea was introduced into the Indian subcontinent as a colonial cash crop to preserve British and Indian commercial interests. However, soon it emerged as a national beverage blurring regional distinctions, occupying its position as a symbol of unity within ethnic and religious diversity. Gautam Bhadra, in his book "From an Imperial Product to a National Drink: The Culture of Tea Consumption in Modern India", argues that before the Great Depression, locally produced tea in India was exported to the UK and Europe, but some of it was consumed locally, primarily within the elite circles in Bengal.

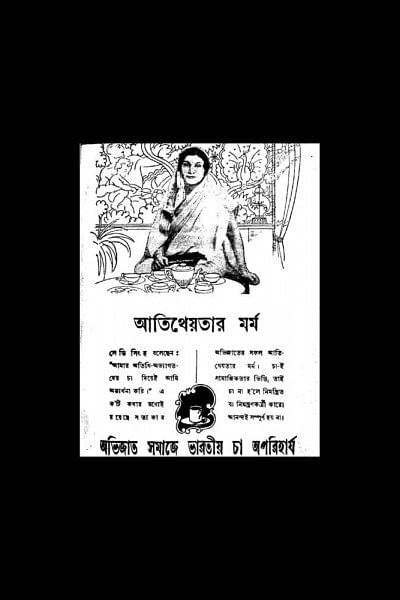

Before the Great Depression, producers with their unsold surpluses looked for inward markets for tea consumption; hence, aggressive advertisements were forged to infuse the demand for tea into the fabric of the society. In the 1930s, tea was disassociated from its imperial nature and a new image of tea was formulated. In this new version of tea adverts, tea was portrayed as a Swadeshi (indigenous) drink that united a diverse India, serving the purpose of the Indian Nationalist Movement. Moreover, women were frequently depicted as bearers of this new tea culture.

I analysed the construction of the concept of ideal woman examining tea advertisements from 1935-1945 in forty issues of one of the most influential monthly magazines of 20th-century Bengal, Prabasi. The magazine started its journey in 1901 from Allahabad, directed towards the Bengali diaspora in India. However, from 1905 onwards, it was being published from Kolkata. Among the contemporary magazines of its time, Prabasi had the highest circulation number. Rabindranath Tagore was among its regular contributors.

In the construction of femininity in tea advertisements, traditional gendered norms were reiterated. Tea was conceptualised as a family beverage served by women to other women, men, and children, where women played a critical role in ensuring the hospitality of guests through serving tea. The embodiment of exclusive gendered tones created new social norms based on existing societal values. Women were depicted in the multiple roles of mothers and wives. Drinking a cup of tea was not rendered as bringing solo pleasure to the woman; instead, women attained the pleasure of tea in family gatherings or in the comfort of the couple's private moments. These portrayals of women enhanced their functionality as wives, capable of satisfying their husbands.

Through the articulation of these roles, an ideal woman was constructed as an individual who was not preoccupied with herself, instead absorbed herself into the needs of her children and husband. The woman in tea advertisements performed exceptionally well in executing traditional roles; drinking tea was meant to help execute her domestic tasks instead of giving her pleasure in its entirety. In this way, tea advertisements formulated new notions of femininity centred on women's role in the domestic sphere.

These trends can be observed in advertisements throughout the period. Some advertisements during this period claim that tea facilitates the housewife to multitask; it provides her with additional energy to spend quality time with her children after an engaging day of housework.

From 1944, tea advertisements began to include ancient paintings from Ajanta and Ellora caves. Some of these advertisements compared the refreshment that tea brings to a sensualised female body. Images of sensualised gods and goddesses frequently appeared in tea advertisements. One ad embodied tea as an impetus to enliven the sexual lives of married couples. In tea ads that included nude imagery of goddesses, feminine stereotypes were embodied as emblements of high art, legitimising male voyeurism through the depiction of women as symbols of sexuality and nature. Simultaneously, it signified the importance of women's reproductive role in society as consumption of tea supposedly enhanced fertility.

While contemporary tea advertisements in Bangladesh no longer articulate notions of sexuality by containing images of nude gods and goddesses, many of the gendered constructions that tea advertisements manufactured remain with us. Tea continues to be served as a family beverage by women, and advertisements to this day depict images of women as the bearer of tea culture in the family.

Advertisements are produced based on existing societal norms, but the indigenisation of tea through aggressive advertisement campaigns also pronounces its transformative role in instilling new cultural values. Commercials act as powerful catalysts of social change that can introduce new elements in any culture. Advertisement companies and businesses have a more significant role to play in challenging women's traditional role in society and harnessing greater values attached to notions of gender equality.

Namia Akhtar is a postgraduate student at the South Asia Institute of Universität Heidelberg. Email: [email protected]

Comments