The pandemic is the perfect time to consider a basic income scheme

They come early in the morning, calling out to the women of the houses—"Khallamma charta bhaat khaite diben?"—to provide them with a cooked meal. It is striking how many are young able-bodied people, and how much more frequent their visits have become nowadays. They are not always disappointed; many do offer food and cash. The whole scenario is distressing and can seem hopeless, evoking the thought that charity, as Oscar Wilde said, "degrades and demoralises".

Just four months of the pandemic has revealed that despite the significant economic strides Bangladesh has made, we have a population that is very vulnerable to shocks. Moreover, we are vulnerable to climate risks and face a number of natural disasters every year. It is time to recognise that a crisis driven approach to our problems, acting merely as a reactionary measure, continues to place limits on economic growth and keeps the poor vulnerable.

If we look to our demographics, people's incomes come through remittance from migrant workers and through labour in the informal economy. It is the latter group of informal labour that we see today on the streets, reduced to begging—asking not even for money but for food. The migrant workers, on the other hand, are returning in throes as more and more countries prepare to face recession and take up protectionist policies, trying to ensure limited health and livelihood services to their own people first.

World Food Program (WFP) chief David Beasley warned there could be "famine of biblical proportions in anywhere from 10 to 36 countries" as a result of the pandemic. This could be us, although even a few months ago we were hailed for our economic progress, leading us towards becoming a middle-income country. Current debates on the situation are that of livelihood versus lives, but this should not be the case at all.

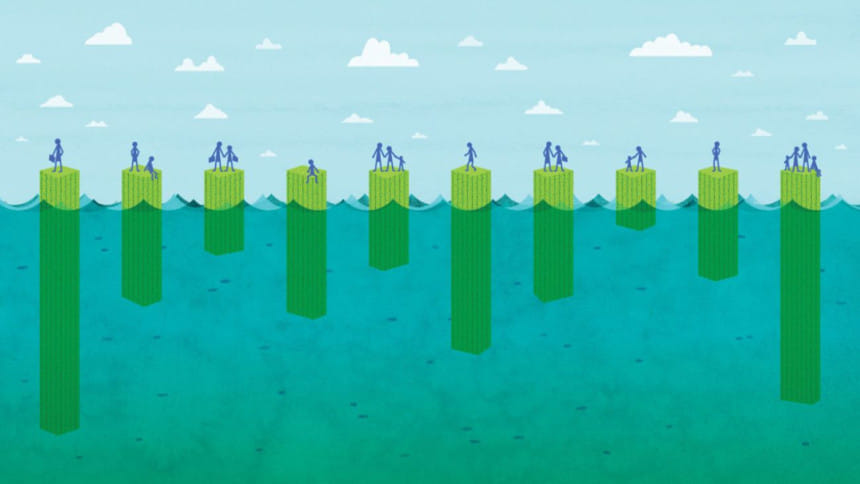

The lower middle- and middle-income households have seen a drastic reduction in their incomes, with thousands unemployed or suffering losses in their small businesses. Various groups like the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling and Centre for Policy Dialogue project that between 30 to 40 percent of the population will be pushed below a poverty line by the pandemic. Adding to that, regular monsoon rains and flooding have already ravaged many parts of the country. These facts imply that food security is a huge concern and basic income to provide for food security is crucial to ensure we survive. Which is why, it is now more important than ever, to introduce a basic income scheme.

A basic income scheme provides a certain amount of money unconditionally to everyone in the population. The amounts given are small, just enough to get by—for Bangladesh, a monthly basic income equivalent to the extreme poverty rate of USD 1.90 PPP (purchasing power parity) will be about BDT 1,700 to 1,800 per person per month. This will be just about enough for food for one person. A household with two adults will have BDT 3,500 per month, enough to feed a very small family. In the past, it may have made sense to segregate social benefits to elders, freedom fighters, government pensioners etc, resulting in about 140 different social protection schemes implemented across 26 ministries. The schemes have also tended to be more rural oriented, while the pandemic has direly impacted urban low-income groups.

To reduce the effects of sudden reactionary measures to shocks and vulnerability, the government should adopt a basic income scheme for the whole population. Implemented continuously and across the whole population, a basic income for all will be more inclusive and will remove any options of leakage due to misidentification of beneficiaries. When everyone is supposed to get an income, there is no need to correctly identify a group. It will also provide for increased money flow in the economy, freeing up additional opportunities for investment and capital growth, or increase savings to reduce vulnerability and provide broad-based protection for sudden shocks. It should be noted that this year's Annual Development Programme (ADP) spending dropped by 23 percent in April. Now that the economy is opening up, there is scope to utilise the funds towards a forward-looking scheme such as basic income to shore up consumption and drive the economy.

There is sufficient evidence that a basic income is helpful, from cases carried out in emerging economies like Kenya, Brazil, India, etc. Basic income will give people purchasing power and allow people to make choices on what their most pressing necessities are and at what quantity, as opposed to food handouts. A basic income scheme available to all is about addressing the issue of food security at a population level rather than at a selective individual level. By virtue of not discriminating against rich or poor, it takes away the operational nightmare of deciding who should or should not get a basic income. All members of the adult population—everyone with an NID—can be reached. It can be transferred to a bank account, mobile money account or micro-finance account of a person, neatly done without any physical interaction. This can reach about half the population—approximately 50 percent of adults in Bangladesh have access to financial services of some kind. All such accounts are linked to an NID or mobile network and the government can send money to an account of each individual. People that are unbanked can be traced through their NID or through the mobile operators they subscribe to, to get their allocation. In the long run, this group too will have an incentive to join the formal financial service sector as customers.

Government databases can keep track of which person has or has not got the income and that can reduce possibilities of corrupt leakages. Presumably, a basic income scheme that is thus streamlined and non-selective will hopefully not suffer from cases of stolen bags of relief rice and lentils. A universal basic income scheme would also be immune to sudden changes in the demographics of vulnerable populations. If everyone gets the income, it won't matter much whether disasters or pandemics hit the rural or urban poor harder and whether the systems to reach the whole population exist.

Moreover, it is the support the economy needs while scoping out ways to recover from a relentless pandemic without risking lives for livelihood and economic growth. The government has already allocated a total stimulus package of over USD 12.1 billion to support the economy. A basic income scheme paying each adult citizen about BDT 1,800 will likely cost only USD 14.2 billion a year and ensure everyone can at least pay for their own food. It is about time our social safety net programmes are revamped and streamlined. We leave it to our trusted leaders on how to do it, with belief and hope that they will.

Sharmin Ahmed is a consultant at IFC, and Sadia Ahmed is an economist by training.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments