Why are Indigenous students falling behind?

Before Aung (name changed) had attended his first university class, he became the subject of a post on his batch Facebook group. A batchmate wrote, "The Adivasis got in only because of the quota. Their scores were lower than ours." Another wrote, "They even get to study higher ranked subjects!" As classes started, Aung found himself struggling to approach teachers and seniors for academic help as he was constantly reminded of his position in this new competitive landscape.

Post secondary education in cities and towns fuels the dreams and hopes of a student. However, among remote Indigenous communities, only a few handful of students get a shot at it.

The literacy rate among Indigenous communities is far lower than the national rate. According to Bangladesh Bureau of Educational and Information Statistics (BANBEIS), the dropout rate was 59 percent in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), whereas the national rate stood at 19.2 percent in 2016. Children can't reach schools because of poverty and distance. Many suffer from illness such as typhoid and diarrhoea, or face a shortage of supplies and textbooks.

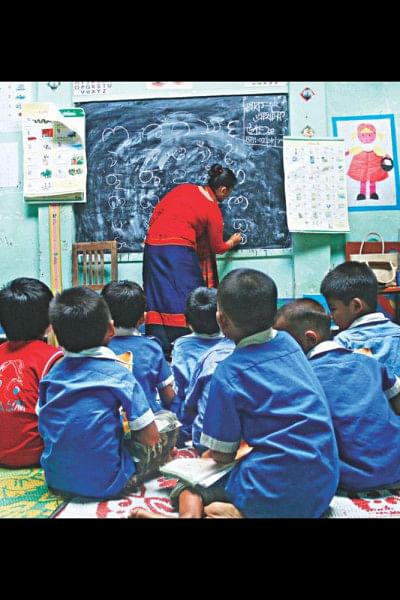

Even when Indigenous children from plain land and hills reach the classroom, their first experience with formal education starts with being admitted in a local primary school where most of the teachers are Bengali. The students mindlessly memorise Bangla rhymes that have no connection with their culture and context. When the children read Bangla text, they can decode, but cannot comprehend. As a result, they fall behind without a proper grasp of Bangla.

In 2018, the government distributed textbooks in five Indigenous languages—Chakma, Marma Garo, Sadri and Tripura—among pre-primary students. Santals, Urao, Mahali, Khak, Humir, Muchi and others were left out of the list. It turned out that most teachers could speak in the languages but did not know how to read or write them. Only 38.6 percent of the 4,204 ethnic community teachers in the CHT attended a 14-day training on their respective languages organised by district councils.

Upon finishing secondary education, students face the challenge of navigating tertiary education in English. The topics are complex, and students are expected to appear for exams in a different language while access to resources remain constrained.

Adaptation to the new environment is still a long haul as they become aware of a demeaning narrative centring their way of life. They are labelled "backward" and "belonging to the past". Their knowledge and skills are discussed as inferior or invalid compared to "modern" knowledge and skills. Comments such as "Tomra shaap, bang khao?" (do you eat snakes and frogs?), "Oi Jonglee!" (Hey wildling!) and "Adibashi ra Ugro hoy" (Indigenous people are uncivilised)—place an extra pressure on Indigenous students to defend their lifestyle when they have just arrived in the cities for higher education.

Their peers fail to see that the natural environment is what makes the knowledge of Indigenous people unique and different from that of any other. The communities have known an incredible variety of foods available in their territories. Traditional knowledge has been stored in the collective memory of Indigenous communities for decades. This knowledge is expressed through stories, songs, folklore, proverbs, dances, myths and agricultural practices. Derogatory attitudes terming Indigenous lifestyles as unhygienic undermines Indigenous peoples' relationships with their lands and ancestry. Public and private discourse are constructed in a way that erases their roots.

Demeaning narratives lead to bullying. Mocked for their "unsmart" pronunciation, Indigenous students remain silent to avoid the humiliation. Many Bengali students call them hateful names based on Indigenous features—Nak Bocha, Chinku. When Joy Tripura (name changed) complained to a teacher at his boarding school, he was woken up at 2am that night. A group of students continuously kicked his door, threatening to beat him up. Think of it—could they have done it if Joy was not alone? How would you focus on your studies if you felt unsafe at a boarding school?

According to the study "Indigenous students: Barriers and success strategies—A review of existing literature" published in the Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, reports about teachers in Canada who treated their Indigenous students with prejudice outnumbered reports of teachers who were fair and open-minded. When students who discriminate are not corrected, the situation is condoned and the discrimination of Indigenous students is affirmed indirectly.

When Indigenous students learn from their peers that Indigenous peoples' ways are backward, they may consequently view their elders as backward or inferior. They experience stress and a feeling of walking in two different worlds.

As a result, Indigenous students face isolation and retreat into their own circles. Unlike the cool kid gang or the nerd club, their circles lack role models, resources and confidence. Think of it—if you've never even seen someone from your community ace the Bangladesh Civil Service exam, or you don't have that space to study and go through those processes that other kids do, you just don't know how to do it.

This is how Indigenous students become vulnerable to social disadvantage, a situation of not having the opportunity to participate fully in economic, social, political and cultural relationships, and is associated with poor performance in class.

Look around in your class. Do you see any Indigenous student? Unlikely. If you do, chances are they wouldn't have been there without the quota system. There is no shame in admitting it.

Indigenous children around the world have long been denied the right to celebrate their roots while getting a comprehensive education. They're up against major inequalities, from structural racism embedded in school systems to inaccurate retellings of history. On campus, they lack social, political, cultural and economic capital.

A vast majority of Indigenous students are slow as a result, but it does not make them lazy. Indigenous students will continue to be slow unless attitudes towards them are changed. Indigenous students can be as exceptional as the next person. The key to success of an individual is to nurture a positive sense of identity and to engage positively with the community. Can we ensure our Indigenous students of these?

Myat Moe Khaing is a marketing strategist at a multinational company.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments