Why I do not support the killing of 'rapists' by 'Hercules'

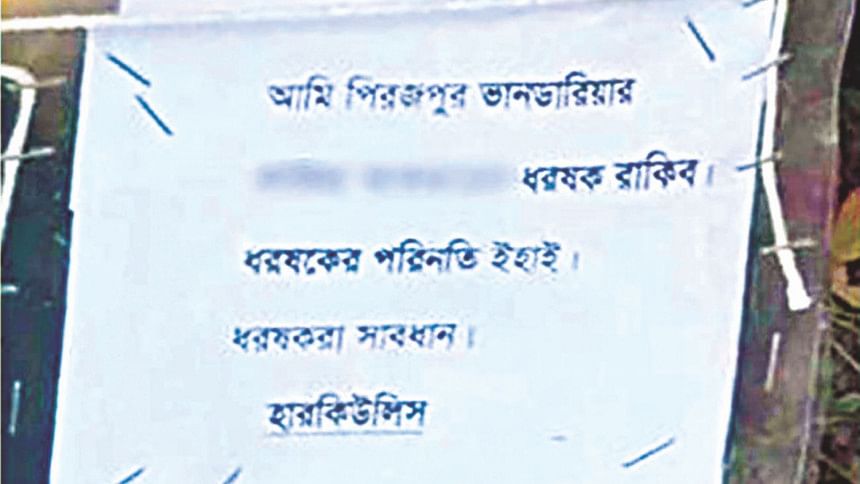

Recently, the bodies of three "rapists" have been found shot to death with culpatory notes hanging around their necks. On January 17, the first body was found by the police in Savar, whereby Ripon, who was the key suspect in a gang rape and murder case of a female garment worker, was found dead with a note that read "I am the prime accused in a rape case." On January 24, the second body was recovered by the police in Jhalakathi, with a note that read "I am Sajal. I am a rapist and this is my fate." On February 1, the third body was found, also in Jhalakathi, but this time the note read "I am Rakib, I am the rapist of a madrasa girl of Bhandharia and this is my fate. Beware rapists – Hercules". Sajal and Rakib were the two accused in a gang rape case of a madrasa student that took place on January 14. These killings are being attributed to "Hercules" since the note on the last body was signed by this pseudonym. This spate of killings has been overwhelmingly well received by the public, with people extending their deepest "respect", "salute", "love" and admiration to Hercules on social media.

It is deeply alarming to see the blind hero-fication of this Hercules by many otherwise educated individuals as some sort of feminist crusader against social injustice. Undoubtedly, any conscientious citizen ought to be frustrated with the state of justice in our country, whereby rapists enjoy virtual impunity for their gross crimes. For instance, a 2013 UN multi-country study on male violence (which surveyed perpetrators of rape) found that in Bangladesh 95 percent of urban respondents and 88 percent of rural respondents reported facing no legal consequences for raping a woman or girl. Furthermore, a recent study by Prothom Alo found that out of the 5,000 rape cases lodged in Nari-O-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Tribunals in Dhaka district between 2002 and 2016, punishment was given in only three percent of the disposed cases. Thus it is perfectly understandable why many citizens may have lost hope in the law enforcement and judiciary as upholders of justice. However, is cheer-leading an onslaught of extrajudicial killings by an unidentified vigilante (however noble their intention maybe) the path to a safer country? It is important to note that while all three men were accused of rape, a formal investigation followed by trial was still pending. Thus, on what ground are we allowing someone the licence to kill at will and a free pass to breach the very foundation of our criminal justice system: innocent until proven guilty? Are we as a society then saying anyone and everyone has the permission to shoot on sight whoever they deem to be a criminal?

As soon as we let individual members of society decide what does and does not constitute a "crime" and allow them to execute punishments for it, rather than a properly appointed judge, we go down a very slippery slope. We move towards a reality where each of us lives at the mercy of someone else's (subjective) sense of public morality. This would be particularly problematic for women since in a deeply misogynistic country such as ours, women are especially susceptible to moral policing by society. For instance, certain members of society think it is a "crime" for women to even step out of the house to work and defy other forms of androcentric cultural norms. What kind of power would this new system of "justice" be giving to them?

In fact just a few years ago, Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (Blast), Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK) and numerous rights activists fought long and hard to have the High Court declare all forms of extrajudicial punishment to be unconstitutional after incidents of women and girls across the country being caned, lashed or otherwise publicly degraded by community elders for "offending public morality" came to light (63 DLR 1). One such incident was in 2010 whereby a woman in Cumilla was subjected to 39 lashes after a shalish took place on the disputed paternity of her child born out of wedlock. It is therefore deeply ironic that so many of us today are celebrating the extrajudicial punishment in the form of Hercules killings as a victory for women's safety. Even if the three men who were killed were actually rapists, who is to say that tomorrow someone will not kill their opponent (political or otherwise) and hang a note describing them as a rapist? That is the main trouble with allowing any random citizen to execute punishments without any formal investigation process: someone need not actually have committed the crime, but merely accused of doing so by someone else.

Undoubtedly, the legal system is flawed and the Hercules killings should most certainly invoke deeper introspection on part of the law enforcement agencies as to why so many citizens would rather entrust a vigilante than a police officer or a judge. However, the inefficiency of the justice system should only ever be used to help contextualise the vigilantism but never to support or justify its existence. Those who really want to make the country a safer place for women must take the more strenuous route to lobby for and implement law and policy reforms from the very grassroots level instead of giving in to our baser instincts and letting our country succumb to disorder and mayhem. We should, therefore, be careful to not let our thirst for speedy punishment obliterate the very bedrock of our justice system and create a state of lawlessness, the ultimate victims of which will almost certainly be the very women we set out to "protect".

Taqbir Huda is a Research Specialist at Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) and can be reached at [email protected].

Comments