Dhaka's vanishing public spaces

With uncontrolled urbanisation (which essentially refers to a "population shift from rural to urban areas enabling cities and towns to grow") innumerable issues related to the very liveability of Dhaka city have occupied the imagination of activists, journalists and academics for quite some time. For the past few years, Dhaka has consistently ranked as one of the most unliveable cities in the world as per global indices. This resonates with many of us residing in the capital for whom the state of liveability is obvious to the naked eye—from the unavoidable and unbearable traffic congestion to the homeless sleeping on footbridges and sidewalks. We, the residents of the city, don't need a global liveability survey to tell us just how horrible the situation is; it is but a mere reinforcement of the reality that we live with everyday.

In the broad context of urbanisation and the concomitant woes, the alarming decline in public space (in the literal sense) and the lack of attention on the issue is particularly disturbing. I understand that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to comprehensively address the byproducts of urbanisation, especially that of a city like Dhaka. But with the uninhibited boom in population of Dhaka—which is set to be the third most populous city in 2050 with about 35.2 million residents—and its ill-conceived urban planning, the dearth of public space and its social implications are a serious concern for people in this growing urban sprawl.

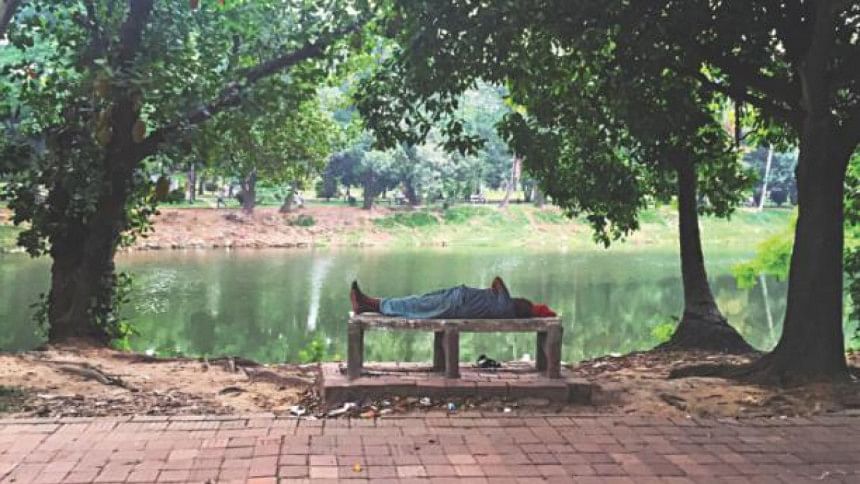

Public spaces breathe life into the social fibre of a community. It is the open markets, plazas, parks and squares, and high streets that give respite to city dwellers from the daily hustle and bustle of city life. Children chasing one another across a field. The elderly taking a stroll in a neighbourhood park. People gathering to watch a street magician. Women socialising at the local fruit market. Men sipping tea by a small lake. Such are the scenes of a city that nurtures and values its urban environment, and makes the public space accessible to city dwellers.

But in Dhaka, such glimpses of free contact and spontaneous movement of people are rare in the public space which in reality has become somewhat of an eyesore: roads choked with traffic, piles of garbage discarded in the open, streetsides occupied by hawkers, poorly maintained (and ugly) buildings, etc. (It should be kept in mind however that urbanisation of Dhaka is a phenomenon of the post-independence period and the concept of 'urban planning' is relatively new in a country where more than half its population still reside in rural areas.) Post-1971 the city's design and planning has not matched up to its accelerated growth leading to the loss of land and a glaring paucity of areas designated for public use.

The need to save our existing valuable public spaces is heightened in light of unbridled urban expansion. Urban public spaces enhance human happiness and empathy as they are the locus of human interaction. They serve as an outlet for experiencing human contact. They are the locale of the most important subject in life: people.

Michael Douglass, a liveable cities expert, contends that there are two competing models of cities: one is based on economic growth and the other on satisfying the basic needs of people in the context of limited natural resources. The former is focused on consumption of products that people believe will bring them pleasure which is (artificially) measured through GDP or growth rate of the national economy, whereas the latter is based on human connection—networking with family, friends, neighbours. While in one model, happiness is up for sale and is intricately linked to the purchase of big houses and expensive cars, in the other happiness is freely available in the form of relationships with people.

As per Douglass' characterisation of city models, it becomes clear what trajectory Dhaka's growth model is on. It only takes a five-minute walk in the unforgiving streets of Dhaka to see just how strangulated its environment has become—devoid of public space. In the modernist view, parks and plazas are considered a waste of space that could otherwise be utilised for economic purposes. Thanks to Dhaka's rapid commercialisation we now have an array of shopping malls and restaurants which are mostly frequented by the well-off—an unholy mixture of classism and consumerism on stark display.

The notion of a 'public space' is perhaps alien to most youngsters in Dhaka who have spent their childhoods glued to computer screens. Whereas children in the era preceding the peak of urbanisation relished outdoor sports and activities, where they had an active role, children (and adults) today have become passive spectators due to an overreliance on technology and the rapid erosion of available public space due to the latter's unabated private appropriation.

These discordant surroundings are anathema to human beings because we are inherently social animals that crave human contact. The preservation of public space—the connective tissue in an increasingly isolating atmosphere of urban life—seems to be missing in the model of Dhaka's progress and development. All that is labelled as progress is not always a sign of improvement and a consumption-led mass behaviour isn't a sign of happiness. In a society where the private realm is fast encroaching upon people's lives—private homes, private cars, private workplaces, privatised multiplexes—the role of the 'public space' is all the more instrumental in shaping urban life.

The writer is a member of the Editorial team at The Daily Star. E-mail: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments