An open letter to the makers of ‘Nikhoj’

Dear Reehan Rahman,

My father, photojournalist and editor Shafiqul Islam Kajol, was added to the list of hundreds of Bangladeshi victims of enforced disappearance on March 10, 2020. He was then 51-years-old, not unlike the idealist protagonist Farooq Ahmed (played by Shatabdi Wadud) in your recently-released web series, "Nikhoj."

Even more coincidentally, my mother, Julia Ferudouse, is a cancer patient just like Farooq Ahmed's soft-spoken wife Rabeya (played by Shilpi Sarkar). My younger sister, Poushi, like Farooq Ahamed's benevolent elder daughter Safia (Afsana Mimi and Orchita Sporshia), takes an interest in musical instruments. However, I, Polok, do not share any similarities with Farooq Ahamed's petulant son, Saif (Shamol Mawla and Masum Rezwan), who, after his father's abduction from the dinner table by men identifying themselves as law enforcers, becomes a troublesome drug addict. He selfishly leaves his family for the US and eventually gets completely detached—only returning to Bangladesh after many years to get married.

In contrast to Saif, his sister Safia keeps searching for their missing father relentlessly throughout the series, mostly through apolitical means. Unlike Saif and Safia, I stood against the tides, mounting a groundbreaking movement called "Where Is Kajol?" to find my father for over 53 days, during which his whereabouts were unknown. On the 54th day, when he was brought before the court under four cases filed by MP Saifuzzaman Shikhor and other ruling party affiliates, I did everything I could to free him. Finally, after the 14th bail plea, he was granted bail—after suffering physically and mentally in prison for over seven months. While he was in jail, writer and entrepreneur Mushtaq Ahamed died in prison. Both Mushtaq and my father were sued under the draconian Digital Security Act.

My father's alleged crime was sharing newspaper articles from his social media account. For that, the kind of nightmares that ravaged my innocent father's life were beyond words. Our family was not spared, having to go nine months without seeing him. I want to say that I think you can understand our trauma, but after watching your web series I can see that you do not.

I, along with my family, watched your confusing series over two days, which at times felt like paid content from those in power. Frankly, "Nikhoj" utterly disgusted my father and he could not bring himself to watch it. My mother managed to sit through almost four episodes, and my younger sister followed my mother's suit. However, I decided to finish watching it. At least the camera work and lighting felt a bit realistic, and this is precisely why "Nikhoj" is such a dangerous predicament.

Additionally, seasoned actor Afsana Mimi's credible performance and her hold over her fanbase further complicate the problem. Ironically, against all the top-notch technical elements and popular actors that you gathered, your vessel drowned in the same oil that you carefully served on a platter. From whom? Only you can answer.

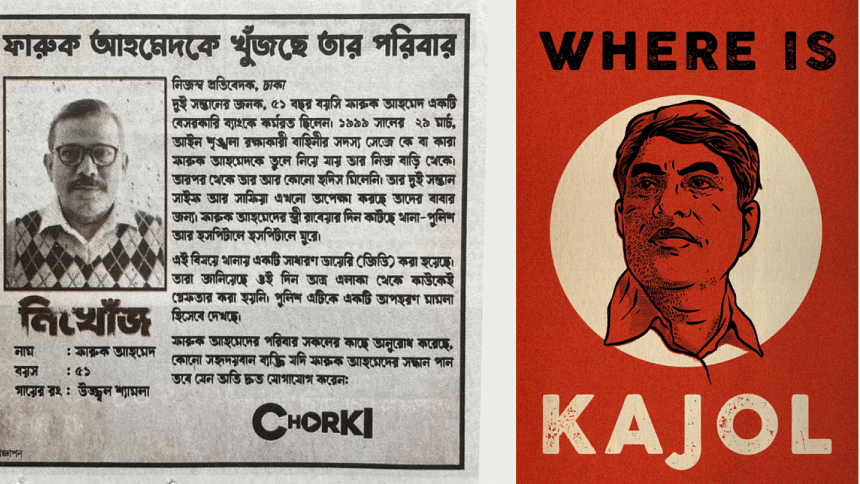

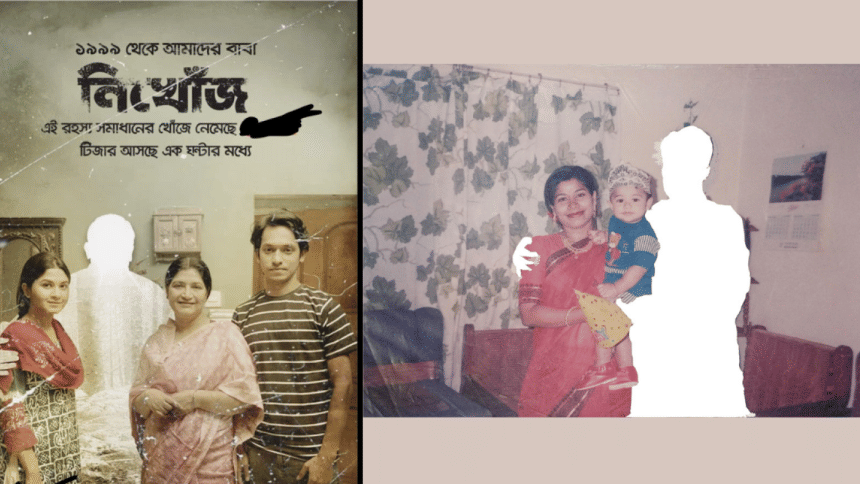

At this point, you may wonder why I am comparing "Nikhoj" to the reality of Bangladesh. Trivial similarities like Safia-Saif and Polok-Poushi, are not my primary concern. These uncanny similarities might be coincidental, right? In reality, they are absolutely not. One Monday morning, while I was at one of my part-time jobs (out of the four that I am currently holding after dropping out of university, due to the fact that my father cannot secure a job or run his newspaper), I got a call inquiring if my father is in any way involved with the web series, "Nikhoj." Then one call after another, followed by countless emails and messages, asked the same question. To my surprise, I saw—on The Daily Star—that the promotional poster for this web series had copied a poster that I put out when my father was missing.

At the very beginning of my movement, "Where Is Kajol?" I manipulated our family photographs by erasing my father from these intimate photos to show the absence of our beloved father in our lives. Your poster did the same with Farooq Ahmed's family portrait. But in "Nikhoj," you portrayed the missing man as a criminal and justified his enforced disappearance. In Bangladesh, many families are still waiting for their loved ones to return. How do you think they feel about your calculated drama? When the Digital Security Act is being used to silence critics, in a way, you criticised the victim of a heinous crime, and on top of that, you stole from a movement that stood against enforced disappearances.

A few weeks ago in Putin's Russia, knowing it might cost her life, a TV journalist stood against the propaganda of her own channel, resulting in her immediate arrest. Many Bangladeshis expressed their frustration on social media. When is any Bangladeshi going to have that kind of boldness? Alas! You directed a series, voluntarily painting an enforced disappearance victim as a criminal, furthering the grand narrative of those in power.

Your sycophantic fairy tale went on. You have not hidden your intentions in subtlety. In one scene, a modest minister serves his subordinate a humble lunch from an ordinary tiffin box—explaining that he cooked the lunch by himself as his beloved wife was out of town. In your series, "Nikhoj," the poor minister does not even have a helping hand to cook for him when his wife is away. Do you know any such minister in Bangladesh? Did you not have sufficient budget to show expensive wristwatches?

As the scene progresses, the minister admits that they are holding an enforced disappearance victim and are afraid of the media finding out about it, mildly scolding the officer. The modest minister humbly asks if they can force a confession out of the victim as soon as possible, fearing blowback from the media. Your cinematic attempt to portray ministers and special officers, trying their best to do their "jobs" as humanely as possible given the situation, is nauseating to watch. I could not stop grinding my teeth as I finished this scene.

To further amplify your narrative, in two separate interviews with The Daily Star, Afsana Mimi states that "there is no denying that 'Nikhoj', is realistic," and Shatabdi Wadud claims, "It ['Nikhoj'] is a contemporary story." Once again, "Nikhoj" purports that a victim of enforced disappearance is a criminal, and the law enforcement agency behind this disappearance is on the side of justice, trying to protect the motherland from those miscreants. Is that the realistic contemporary story these renowned actors are talking about?

Human Rights Watch writes that "according to Bangladeshi human rights groups, nearly 600 people have been forcibly disappeared by security forces since Prime Minister Hasina took office in 2009." In December 2021, the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances said it knew of "86 documented cases [of enforced disappearance in Bangladesh] in which the victims' fate and whereabouts remain unknown."

Is "Nikhoj" a realistic story or not? Please let the victims of enforced disappearance and their family members know.

Monorom Polok is a freelance writer, activist and the founder of "Where is Kajol?"

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments