Is repatriation the only way for Rohingya refugees?

Recently, the US officially recognised the coordinated atrocities against the Rohingya Muslim minority, perpetrated by the Myanmar military through a bloody "clearance operation," as "genocide," the gravest of crimes. Within the first three weeks of the deadly military crackdown in August 2017, Bangladesh took in more refugees than the entirety of Europe did during the Syrian crisis. Since then, Bangladesh has been generously sheltering more than 1.2 million Rohingyas on humanitarian grounds. Following this refugee influx—the fastest and largest—Bangladesh and Myanmar signed two bilateral agreements in 2017 and 2019 for the repatriation of these forcibly displaced Rohingyas. But due to the reluctance and non-cooperation on Myanmar's part, repatriation remains a distant reality. The situation has become further complicated due to the ongoing conflict between the military regime and the pro-democracy front, following the audacious coup on February 1, 2021.

However, Naypyidaw's recent proposal to take back 700 Rohingyas frustrated Dhaka, as the former compiled the "verified list" in a way that apparently showed its "lack of goodwill" for repatriation. Again, the question arises: Is repatriation the only sustainable solution to end the plight of the stranded Rohingyas?

But, as per the legal maxim of William E Gladstone, "Justice delayed is justice denied." As almost five years have elapsed without an enduring solution, it's high time we rethought a viable way out of this crisis. The 1951 Refugee Convention, a universal treaty on the status and rights of refugees, could be a legal statute to resolve any refugee crisis with three possible solutions: local integration, resettlement in other countries or voluntary repatriation. An in-depth assessment of those options, discerning distinct spectrums of the crisis, could offer one that would be feasible in resolving the protracted Rohingya crisis.

An impact assessment study, jointly conducted by the UNDP and the Policy Research Institute, unveiled the immense socio-economic pressure and environmental costs of supporting Rohingya refugees for Bangladesh, an already overpopulated country with more than 165 million people. The total geographical area of Bangladesh is 147,570 sq-km, 92nd in terms of country size, and smaller than the US state of Iowa. It is understandable why it is impossible for Bangladesh to accommodate 1.2 million Rohingyas—more than the total population of Bhutan—on its limited land. Moreover, Bangladesh, which has long been struggling with its own unemployment problems, has neither the financial capability to ensure basic needs and life-saving assistance for the Rohingya refugees, nor provide them with employment opportunities.

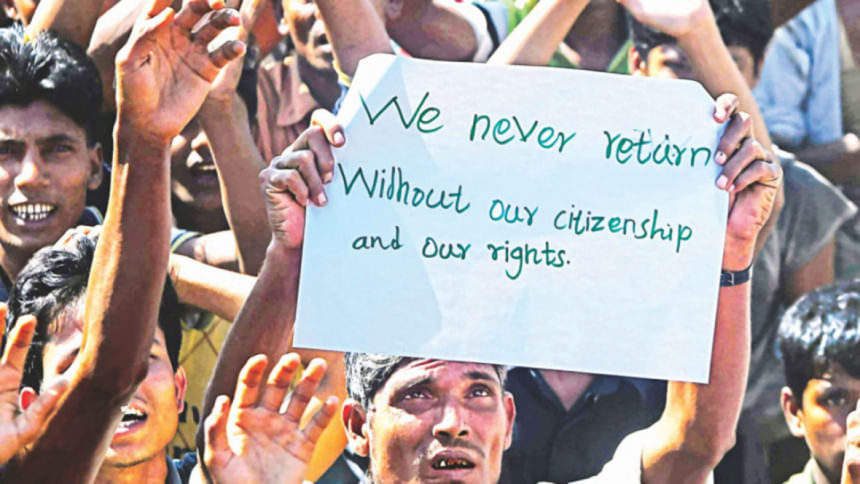

Arguably, even if Bangladesh started integrating the refugees locally, it would motivate the Tatmadaw not only to continue delaying the repatriation, but also to conduct its brutality on around 600,000 Rohingyas now living in Myanmar, and to make them stateless. Besides, the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights stated point-blank that they did not want Bangladeshi citizenship, and would rather go back to their homeland. So, integrating them locally, against their will, would equate depriving them of fundamental and human rights. This is why the World Bank has been recently hit with extensive criticism for its proposal of local integration—an unacceptable solution on all grounds—of Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh.

Apart from Bangladesh, the members of this persecuted minority are now living in 19 other countries. As of today, no other country has expressed interest in granting citizenship to the Rohingya refugees with due economic and social rights. As the countries with the capability to accept Rohingyas are already struggling with the global refugee problem, it is illogical to expect that they would resettle millions of Rohingyas as citizens. According to the UNHCR, around 84 million people worldwide have been forced to flee their homes, of whom more than 26 million are refugees. The number has been intensified by the recent Ukraine war, which has resulted in the second largest ongoing refugee crisis in the world, after Syria. As overseas resettlement is a voluntary option, depending on the willingness of third-party countries, it should not even be considered as an option until any large country, in terms of geographical area and financial capability, wilfully declares their acceptance of Rohingya refugees.

Given the socio-economic conditions of Bangladesh and the intense global refugee crisis, dignified repatriation ensuring internationally monitored safe zones remains the only sustainable solution to put an end to the Rohingyas' struggles. As formal diplomatic manoeuvres see no light at the end of the tunnel, Bangladesh may venture into informal diplomacy as well. Though the Tatmadaw is directly ruling Myanmar now, they indirectly ruled this quasi-civilian state, as a near-deep state, even when they were not in power. This is why defence diplomacy, especially military-to-military cooperation, could be fruitful not only to understand the Tatmadaw's psychology, but also in convincing them for the safe and dignified repatriation of the Rohingyas. Also, deepening bilateral ties through economic dependency, such as exploring unexamined avenues of economic sectors, leasing agricultural lands, importing natural gas, etc between these two neighbours could also be helpful. Obviously, this does not mean that Bangladesh should stop pushing world communities to exert continuous pressure on Myanmar to expedite the Rohingya repatriation process and end the cycle of systemic abuse against the Rohingyas. Instead, Bangladesh should leave no stone unturned to ensure the safe and dignified repatriation for the most persecuted minority of our time.

Hussain Shazzad is a strategic affairs and foreign policy analyst.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments