Why economic forecasting is now trickier than before

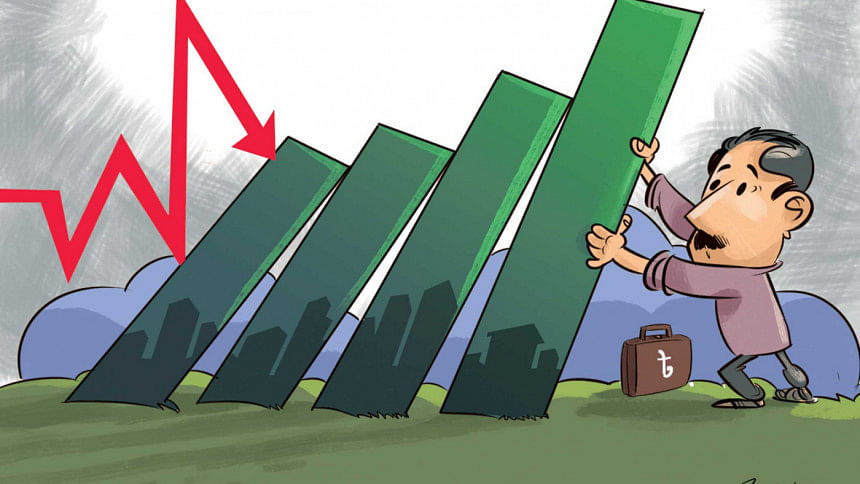

Bangladesh has some very difficult—and one could say unpredictable—times ahead in the coming years. I do not want to raise the red flag or be too alarmist, but who knows what the future holds for a country trying to forge through uncertain times and tackle the many dangers that are coming its way: bad weather, non-cooperative foreign governments, competitive foreign markets, unfavourable trade regimes, cyberattacks, etc.

Bangladesh must cross several milestones along the way as it marches forward. To name a few, the country aims to graduate from the LDC status in 2026, become an upper-middle-income country (UMIC) by 2031 and achieve high-income country status by 2041. In addition, there are stiff development targets to be achieved by 2030 under the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

As an economist, you frequently encounter questions about the future. These questions are on my mind, too. For example, "When will Bangladesh reach the middle-income country status?" "What will be its GDP growth rate next year?" "Can our RMG exports reach the USD 50 billion target soon?"

These are legitimate questions and often I find myself scratching my head to find the answers. Forecasting future economic growth is the job of an economist and we are trained to do so. We also are aware of the many pitfalls that one faces when we try to look into the future. The biggest obstacles on the path to accuracy are: 1) Uncertainty, 2) Lack of data, and 3) Limitations of the tools or models.

Uncertainty has been a big factor in upending the economists' forecasts. GDP growth rates in almost all countries slowed down in the last quarter of 2021, and all forecasts have been proven wrong. Even the USA and China are expected to experience slower growth in 2022. US GDP growth will decline from 5 percent last year to 4 percent this year, and China's from 8 percent to half that number. Since China's economy has been the main locomotive of global growth in the last few years, "broader economic outlook is beginning to dim," according to The New York Times. But don't be surprised if we see another revision in mid-2022.

It would be great if we could always foresee the future like Jeane Dixon, the well-known American psychic and astrologer who gained fame by claiming to gaze into her crystal ball and predict future events. Dixon was well-known for her ability to anticipate major global events including the death of John F. Kennedy and the Munich Olympics massacre. But she also missed her mark more often than not.

Forecasting the future of GDP, the price level, unemployment or other less known economic variables is usually based on econometric models. However, there are different categories and brands of models, and they vary in terms of complexity and focus. It is well-recognised that models can never be expected to forecast with 100 percent accuracy.

Also, each model has its own strengths and weaknesses. They often reflect the biases of the economist or the institution that creates and operates the model. For example, a conservative think tank that has a strong aversion to tax increases can be expected to show that any increase in corporate tax or in personal income tax for the rich will slow down economic growth. Similarly, a liberal body might project that spending more government money on social programmes will promote healthy growth.

Forecasters also fudge the numbers and often fail to give a full account of any policy measure. An example of this tendency to mislead and of the disagreement among economists was evident in the divergent estimates of the impact of the Trump-era tax cuts on the budget, GDP, and the debt burden.

The conflicting economic forecasts in the present uncertain times are obviously raising some concerns. On January 4, 2022, The Wall Street Journal raised the alarm with a headline-making announcement: "Forget about trying to forecast 2022", and warned that economic predictions this year could be trickier than usual. A peer-reviewed journal article shows that economic forecasts made more errors during uncertain times.

Central banks have typically been very secretive about their decision-making process, particularly with regards to the assumptions they make in formulating their policy decisions. The US Fed, which is more forthcoming in this regard, reported in December that its governing body "did not yet see the new variant as fundamentally altering the path of economic recovery". In other words, the US Fed did not anticipate the economic downswing that came in late December and January.

In sharp contrast to this optimistic view, Omicron cases have risen very rapidly even though most countries have imposed relatively few restrictions. A large number of people, sick or worried about getting sick, have been staying home from work. Many others are cancelling plans to go for vacations or staying away from in-person activities such as eating out. Consumer spending in many countries ended last year on a down note. And if the Covid cases rise again, there is an increasing risk that consumers will keep a tighter grip on their pocketbooks.

Let us consider the latest data from the world's largest economy, the USA. In mid-January, the US Department of Commerce reported that retail sales fell by 1.9 percent from November to December. And this decline was across the board. Department store sales dipped by 7 percent, electronics and appliances fell by 2.9 percent and non-store retailers, of which Amazon.com was the largest, took an 8.7 percent hit.

Several factors are at play here. Supply-chain problems, semiconductor shortages, and Omicron hazards are all still sources of concern. So are shortages of skilled workers and the decline in the service industries. Recent forecasts from major banks and research organisations are somewhat at odds with each other. As of October, before Omicron reared its head, all experts were prognosticating a robust growth in GDP, a booming Christmas season, and upward sales boosted by savings. But now, we see a sudden shift, and some of the hidden factors are again affecting all sectors of the economy.

What about the future? The scenarios rely on the speed of Omicron transmission. Some are optimistic that because it is hitting a lot of the world all at once, the nature of its effect on global supply chains might be different from the experience with previous variants, whose effects weren't so synchronised. But these are possibilities rather than certainties.

The International Monetary Fund will release its World Economic Outlook on January 25, a week later than planned, to factor in the latest Covid-19 developments. MD Georgieva last month told the Reuters Next conference that the IMF was likely to further downgrade its global economic growth projections in January to reflect the emergence of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus. In October, the IMF had forecast global economic growth of 5.9 percent in 2021 and 4.9 percent this year, while underscoring the uncertainty posed by the new coronavirus variants.

The biggest source of uncertainty is obviously the course that the pandemic will take. There is a strong feeling among some public health officials that the worst is over, and the role of the virus will be endemic, similar to influenza. We also learned that the Covid virus mutates in countries with unvaccinated masses—we still have multitudes of them in various countries, both developed and developing.

"Unfortunately," says immunologist Ali Ellebedy at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, "we're still living in uncertainty."

Dr. Abdullah Shibli is Senior Research Fellow at the US-based International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI). His new memoir, "A Fairy Tale: Autobiographical Stories", was recently published by Jonantik.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments