Budget FY2019-20: New directions, old roads

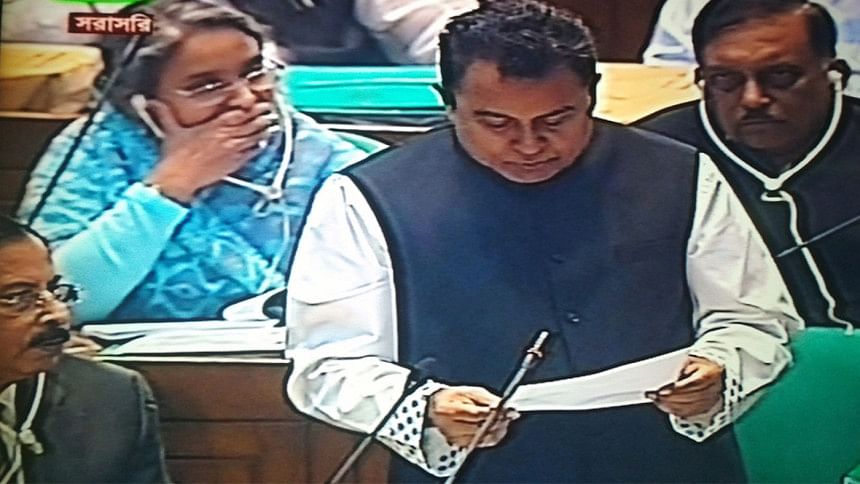

This is the first time we noticed a prominent leader of the opposition using an appropriate word, "ambitious", to describe the budget, instead of branding it as "anti-people." This is a good sign because the first budget for a new finance minister should be forward-looking.

Despite some mistakes (grammatical, spelling errors, and inconsistent usage of both British and American English), the finance minister has sufficiently infused his energy and hopes into the document. But his words aren't simply rhetoric—rather, he has come up with definite target numbers for the next four years. Those numbers reflect commitment and are the strongest part of the budget. Other numbers, however, are pretty structured as per the budgetary framework of the ministry of finance, which the finance minister might not be able to manoeuvre within such a short span of time.

Mega development projects must be outsourced internationally instead of unduly favouring inefficient domestic contractors to avoid waste of resources and time. The finance minister exhibited his passion for all mega projects, but it's not clear why lifeline projects like Patal Rail weren't mentioned even once.

Critics who say that this budget is no different from its previous versions have indeed missed some salient points. The two most difficult goals are raising the GDP growth from eight percent to 10 percent by 2024, and increasing the revenue-GDP share from 10 percent to 14 percent. While we are not sure how much the government can deliver regarding the first part—since output growth is a complex summation of numerous elements—we still believe the finance minister can bring some changes to the second part pertaining to tax collection, given that he is courageous enough to impose limits on affluent individuals. In other words, the finance minister has to be very determined and strict to remove the rusty mindset of the super-rich who dislike paying taxes, and love acquiring but despise repaying big loans. He must act quickly though—any reform needed to design a healthy financial architecture system has to be initiated within the first two years of the regime. The legal changes which are essential to nab the habitual defaulters must be hammered out right after the budget is passed.

A USD 62 billion budget makes up almost 18 percent of the projected GDP of USD 336 billion, while USD 44 billion of revenue covers 13 percent of GDP, leaving a deficit of almost USD 18 billion, which in turn constitutes five percent of GDP. So, structurally, the budget remains the same as before. But the ratio of operating and development expenditures is 61 to 39, while the ratio was 65 to 35 in the early 2010s. This means that the finance minister has kicked off the budget in a good direction, so we can gradually allocate almost 50 percent of the budget for development programmes by 2025.

Although it's not completely appropriate to say that we will be a developed nation by 2041—if one believes in plausible growth arithmetic—we can agree that Bangladesh invariably needs a rising proportion of the development budget for its march toward a prosperous, upper-middle-income country by 2041. And mega development projects must be outsourced internationally instead of unduly favouring inefficient domestic contractors to avoid waste of resources and time. The finance minister exhibited his passion for all mega projects, but it's not clear why lifeline projects like Patal Rail weren't mentioned even once. Dhaka must be saved first to make our progress sustainable. And Patal Rail has no other alternative. The prime minister had made promises about this plan in a pre-election rally.

The manner of deficit financing couldn't have come out of the finance minister's predecessor's playbook. Domestic and foreign borrowings will almost equally share financing in a 50-50 ratio, but the worst part is that almost USD 7 billion out of USD 9 billion allocated to domestic financing will be managed from Sanchaypatra—the most expensive way of deficit financing in the world. The wired nonmarket interest rate on Sanchaypatra is the Trojan horse which the government has been ignoring for a long time—but one that has already started taking a toll on other important allocations.

Let's look at the interest burden, which is close to another USD 7 billion and the substantial part of this hemorrhage is attributable to Sanchaypatra—the so-called poor men's welfare instrument, mostly entertaining the money moguls now. In this regard, the finance minister has to correct his predecessor's blunder, if he really wants to save the capital market, preserve the banking sector's liquidity, and build a strong bond market. There is no alternative other than dismantling this distortive savings scheme, and handing over deposit mobilisation entirely to the banks or fixing Sanchaypatra rates based on five-year bond rates that exist in the market.

What should be the first and most highly prioritised job of a finance minister in any developing country? It's not devoting every thought to banking. That job is for the central bank. A finance minister's main job is to understand the art of devising the most economical way of deficit financing. But, at least in the last eight years, that hasn't been the case. Domestic borrowing is gradually being eclipsed by Sanchaypatra, hence the interest burden is expanding phenomenally, which is an indicator of one of the most inefficient forms of deficit financing in Asia. Now the interest burden alone makes up almost 11 percent of the whole budget, and is higher than the total allocation to the three important sectors of agriculture, health, and housing.

This monster is also bound to overpower sectors like education and transport, unless the new finance minister undertakes reforms. For example, domestic borrowing is only 1.2 times larger than foreign borrowing, but the interest burden on domestic borrowing is 12 times larger than that on foreign borrowing, suggesting just how self-destructive it is to gradually allow more and more domestic borrowing that charges tremendously high interest rates. Higher interest burden is eroding the government's capacity to implement the development budget, weakening future growth potential and threatening employment opportunities. The new finance minister has to get rid of this addiction to Sanchaypatra which has become a convenient tool for acquiring money easily. This reflects fiscal incapacity, and gradually produces distortions in the banking sector.

On the other hand, the allocation for primary education (MPO) and the finance minister's interest to hire expertise from foreign lands (particularly, Bengali expatriates) are praiseworthy. I had the opportunity to visit China's Tsinghua University in 2016 which now ranks number one among 400 top-quality universities in Asia—a list that doesn't include a single institution from Bangladesh. Most instructors we met were the product of reverse migration from America and Europe to Asia. Top Chinese universities offer handsome packages to attract Chinese professors and scientists living overseas, which lead them to eventually return to their homeland. University officials in our neighbouring countries, India and Pakistan for example, attend job fairs to hire foreign individuals with PhDs as faculty members. By contrast, the hiring process in our universities is often plagued with nepotism or partisan influence. Additionally, grants for research are scarce and the evaluation criteria are insufficient. Non-transparent promotion procedures and faulty recruitment policies are the reason why our universities receive low world rankings. It is crucial that the finance minister renders specific allocations to address these deficiencies. Otherwise our embarrassing position as one of the lowest in the Knowledge Economy Index will not change.

This time, we didn't see a term called "non-development" expenses. Rather, the finance minister used the term "operating expenditure." Still, some issues remain. Once the term "deficit" is used, the negative sign before the figure is inappropriate and misleading. "Deficit" should either be replaced with the word "balance" or the negative sign before it must be removed. Last but not least, I'm not sure whether a budget speech should be more than 100 pages long. We would like to see a 50-page budget speech next time that has less words but reflects more dynamism.

Biru Paksha Paul is professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland. His recent book is titled Empowering Economic Growth for Bangladesh. Email: [email protected]

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals.

To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments