Faster than a Speeding Congressman

It's a bird! It's a plane! No, it's Supra-politician. But, unlike a cartoon hero, when Supra-politician arrives in power, he or she probably won't save the day.

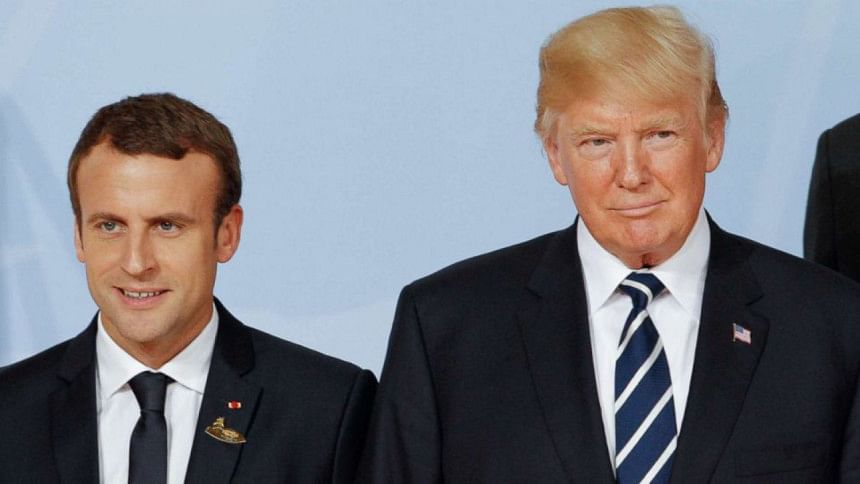

The emergence of such leaders is a relatively new phenomenon, one that is reshaping politics across the West. Today, two largely dissimilar presidents, Emmanuel Macron in France and Donald Trump in the United States, are its leading avatars.

Until a few decades ago, democratic leaders had to climb the electoral ladder, rung by rung, acquiring along the way a facility for retail politics, stump speaking, and the demands of assembling a working majority. In the US, that meant that virtually all presidents had either served in Congress or as state governors, with the only modern exception being Dwight Eisenhower, whose background as an Army general stood in for political experience.

In Europe, French politicians moved up the parliamentary ladder in the Fourth Republic, and could aspire to climb to the presidency in the Fifth. German leaders since World War II have risen through state and federal political structures. In Italy, postwar leaders have had to navigate the byzantine political maze created by the now-defunct Christian Democrats. Even in Russia, leaders have risen through the ranks of party or state hierarchies.

Of course, political parties always had their "talent scouts" on the lookout for individuals with exceptional leadership potential. But even a figure like British Prime Minister John Major, who was fast-tracked to the top, served as a junior social services minister, foreign secretary, and chancellor of the exchequer before taking over the premiership.

Things began to change with Tony Blair's government. Blair had served in Parliament, and performed smoothly as the Labour Party's home affairs spokesman. But, after the unexpected death of his mentor, the skillful machine politician and Labour Party leader John Smith, he was catapulted to the top, as though by divine right. More recently, David Cameron served just one term in Parliament before being chosen as leader of the Conservative Party.

In the US, Trump's predecessor, Barack Obama, was another such a "fast-tracked" politician. In 2004, the relatively unknown Illinois state senator delivered a spellbinding speech at the Democratic National Convention. Four years later, he was in the White House.

With Trump, the rocket to the top fired on all boosters. In just over a year, Trump went from reality-television host and showboating property magnate to leader of the world's most powerful country, leaving the Republican Party establishment with whiplash.

The closest precedent for Trump may be Italy's former prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi, who was a well-known media mogul before deciding to take advantage of the disintegration of Italy's postwar party system in the early 1990s to create his own political movement. Another Italian supra-politician, Matteo Renzi, also enjoyed a meteoric political rise, becoming prime minister without ever serving as an MP, holding national office, or building a political coalition.

Finally, there is Macron, a former banker and (briefly) economy minister, who had never entered the slog of democratic politics before the recent election. Without backing from an established party – like Berlusconi, Macron created his own movement – he surged from relative unknown to President of the Republic in a matter of months.

Clearly, supra-politicians do not subscribe to a particular ideology or cultivate a particular appearance. And there are specific factors that fueled each individual's rise. Cameron was supported by financial interests determined to resurrect the Conservative Party. Trump's business background and "outsider" status helped him to appeal to the newly dispossessed.

But these leaders do have some features in common, beginning with their use of modern media. Prior to the twentieth century, leaders were remote figures who rarely made direct contact with the masses. Then came the age of the orator, when figures like David Lloyd George and Ramsay MacDonald spoke directly to large crowds. Leaders from Adolf Hitler to Winston Churchill did the same, with the aid of the microphone.

The advent of television called for a more personal and understated presentation – brilliantly grasped by John F. Kennedy – and was more conducive than ever to the rapid takeover of public discourse and consciousness. Blair and Cameron may not have been good orators, but they knew how to present themselves on TV. Obama expertly blended oratory with a relaxed, TV-optimal persona.

What Trump lacks in rhetorical skill, he makes up for with his ability to manipulate an audience, with Twitter as his favorite tool for connecting to the masses. Renzi and Macron are masters of the sound bite.

Of course, getting the right TV coverage takes some effort. Trump courted Rupert Murdoch, just like Blair and, to a lesser extent, Cameron had. Macron assiduously cultivated French media interests. Berlusconi's own companies dominated the Italian airwaves.

But there is another, more troubling commonality among supra-politicians: they tend to crash-land, owing largely to their lack of political skill. Blair couldn't reconcile his neo-conservative principles with those of his own party – a situation that came to a head with his disastrous support for the US-led war in Iraq. Cameron's desperation to win votes spurred him to call a referendum on Britain's European Union membership, the result of which forced him to resign.

Renzi's leadership, too, was brought down in similar fashion: by tying his political fate to a referendum on much-needed constitutional reforms, he turned the vote into an assessment of his government. Trump's cluelessness has been on display since day one, undermining the confidence of US allies and impeding the Republicans' ability to enact their agenda.

The question now is whether Macron – who went on to secure an unassailable majority in the French National Assembly – can break the mold, or whether he will provide further proof that media savvy is no substitute for experience in the political trenches.

Robert Harvey, a former member of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, is the author of Global Disorder and A Few Bloody Noses: The Realities and Mythologies of the American Revolution.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2017.

www.project-syndicate.org

( Exclusive to The Daily Star )

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments