If wealth is justified, so is a wealth tax

Economic inequality has moved to the top of the political agenda in many countries, including free-market poster children like the United States and the United Kingdom. The issue is mobilising the left and causing headaches on the right, where wealth has long been viewed as worthy of celebration, not as demanding justification.

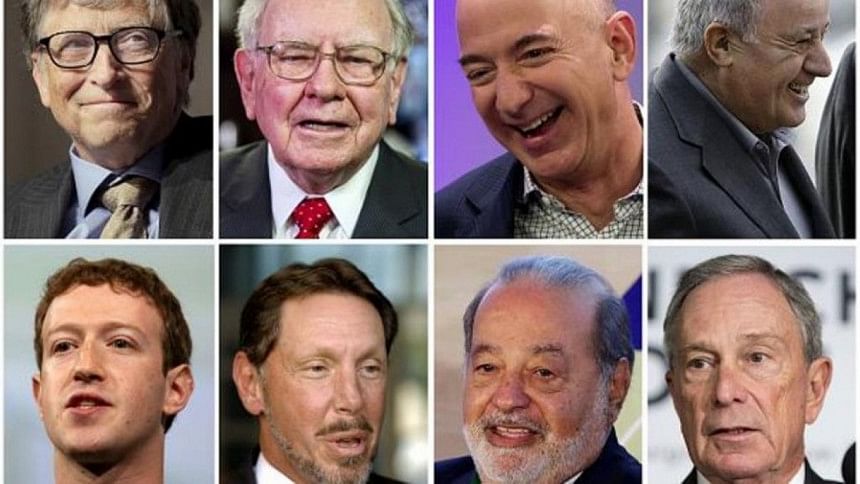

But today's concentrations of wealth do demand justification. In 2018, Forbes listed three billionaires among its top ten most powerful people in the world. Next to the heads of states of Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin, US President Donald Trump, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, one finds not only the Pope, but also Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, and Google co-founder Larry Page. All three owe their power not to public position or spiritual influence but to private wealth.

As contenders in the Democratic primary for the 2020 US presidential election, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts have promised to impose new taxes on the super-wealthy. Warren's wealth-tax proposal—a levy of 2 percent on every dollar of net worth above USD 50 million, rising to 6 percent for fortunes greater than USD 1 billion—has ruffled billionaires' feathers. According to Gates, he has paid more in taxes than almost anybody (some USD 10 billion). And while he would consider it "fine" if that figure had been doubled to USD 20 billion, he believes a much higher tax would threaten the incentive system that led him (and others) to invest in the first place.

For his part, Michael Bloomberg, the founder of the Bloomberg news empire, a former mayor of New York City, and now a Democratic presidential contender himself, argues that a wealth tax might be unconstitutional, and that it would turn the US into the likes of Venezuela. And not to be outdone, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg has suggested that taxing billionaires' wealth would lead to worse outcomes than leaving it where it is, implying that the ultra-wealthy know better than the peoples' elected representatives how tax revenues should be spent.

Note the sense of entitlement underlying each of these reactions. Each man's billions, we are told, belong to him; he earned the money and should therefore get to decide how to spend it, be it on philanthropic projects, taxes, or neither. The billionaires tell us that they are willing to pay a fair share of taxes, but that there is some undefined threshold where the incentives to innovate and invest will be thrown into reverse. At that point, apparently, the ultra-wealthy will go on strike, leaving the rest of us worse off.

But this perspective ignores the fact that accumulated wealth is largely a product of law, and by implication of the state and the people who constitute it. As economist Thomas Piketty demonstrates in his 2014 book "Capital in the Twenty-First Century", the rich today hold most of their wealth in financial assets, which are simply legally protected promises to receive future cash flows. Take away legal enforceability, and all that remains is hope, not a secure asset.

Moreover, the private empires over which today's billionaires preside are organised as legally chartered corporations, which makes them creatures of the law, not of nature. The corporate form shields the personal wealth of the founders and other shareholders from the corporation's creditors. It also facilitates the diversification of risk within a company, by allowing discrete pools of assets to be created, each with its own set of creditors who are barred from making claims on another asset pool, even though the parent company's management controls all of them.

Further, the company's own shares can be used as currency when acquiring other companies. When Facebook bought WhatsApp, it covered USD 12 billion of the USD 16 billion purchase price with its own shares, paying only USD 4 billion in cash. And, as with Facebook, corporate law can be used to cement control by founders and their affiliates through dual-class share structures that grant them more votes than everyone else. As such, they need not fear elections or takeovers of any kind.

Finally, companies whose assets take the form of intellectual property (IP) and other intangibles tend to rely even more on the helping hand of the law. As of 2018, 84 percent of the market capitalisation of the S&P 500 was held in such intangible assets. It takes a legal intervention to turn ideas, skills, and knowhow—which are free to be shared by anybody—into exclusive property rights that are enforced by the full power of the state. And in recent years, Microsoft and other US tech companies have boosted their earning power significantly by promoting US-style IP rules around the world through the World Trade Organization's body for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

To be sure, there are good reasons for states to adopt laws that empower private agents to reap the rewards of organising businesses and developing new products and services. But let's call a spade a spade and a (legal) subsidy a subsidy. While Bezos, Bloomberg, Gates, and Zuckerberg may well be savvy entrepreneurs, they also have benefited on a massive scale from the helping hand of legislatures and courts around the world. This hand is more contingent than the invisible one immortalised by Adam Smith, because its vitality depends on a widely shared belief in the rule of law. The erosion of that belief, not a tax, poses the greatest threat to billionaires' wealth.

Katharina Pistor, Professor of Comparative Law at Columbia Law School, is the author of "The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality."

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2019.

www.project-syndicate.org

(Exclusive to The Daily Star)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments