The US-Saudi relationship after Khashoggi

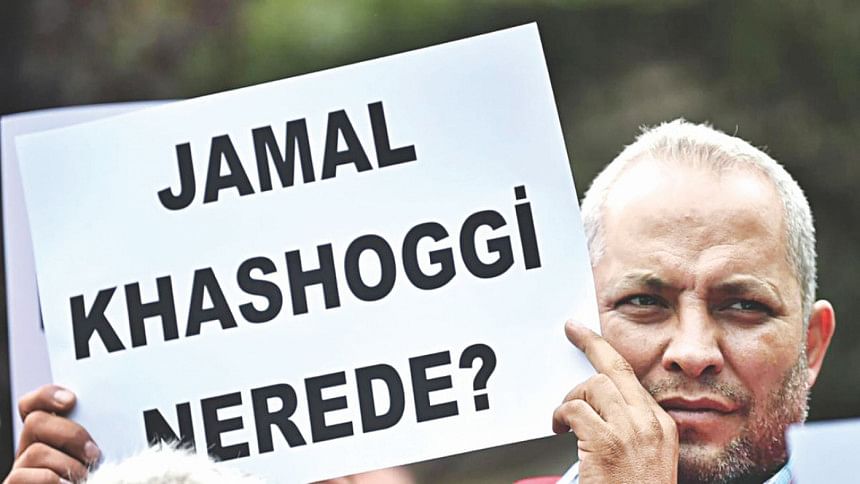

The alleged killing of the Saudi Arabian dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a permanent resident of the United States, in the Kingdom's consulate in Istanbul has unleashed a tidal wave of criticism. In the US Congress, Democrats and Republicans alike have promised to end weapons sales to Saudi Arabia and impose sanctions if its government is shown to have murdered Khashoggi.

But significant damage to bilateral ties, let alone a diplomatic rupture, is not in the cards, even if all the evidence points to a state-sanctioned assassination. Saudi Arabia is simply too crucial to US interests to allow the death of one man to affect the relationship. And with new allies working with old lobbyists to stem the damage, it is unlikely that the episode will lead to anything more than a lovers' quarrel.

Saudi Arabia's special role in American foreign policy is a lesson that US presidents learn only with experience. When Bill Clinton assumed the presidency, his advisers were bent on distancing the new administration from George HW Bush's policies. Among the changes sought by Clinton's national security adviser, Anthony Lake, was an end to the unfettered White House access that Saudi Arabian Ambassador Bandar bin Sultan enjoyed during the Reagan and Bush presidencies. Bandar was to be treated like any other ambassador.

But Clinton quickly warmed to Bandar, and Bandar and the royal court would become crucial to Clinton's regional policies, ranging from Arab-Israeli peace talks to containing Iraq.

Before Donald Trump assumed office, he frequently bashed the Saudis and threatened to cease oil purchases from the Kingdom, grouping them with freeloaders who had taken advantage of America. But after the Saudis feted him with sword dances and bestowed on him the highest civilian award when he visited the Kingdom on his first trip abroad as US president, he changed his tune.

Even the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, could not damage the relationship. Though al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, himself a Saudi national, recruited 15 of the 19 hijackers from the Kingdom, senior Saudi officials dismissed the implications. In a November 2002 interview, the Saudi interior minister simply deemed it "impossible," before attempting to redirect blame by accusing Jews of "exploiting" the attacks and accusing the Israeli intelligence services of having relationships with terrorist organisations.

Americans seethed, and it appeared that the awkward alliance between a secular democracy and a secretive theocracy, cemented by common interests during the Cold War, was plunging into the abyss separating their values. But the alliance not only survived; it deepened. Bandar provided key insights and advice as President George W Bush planned the 2003 Iraq invasion.

Today, American politicians are again ratcheting up their rhetoric following Khashoggi's disappearance. The Turks claim they have audio and video revealing his death, and Senator Lindsey Graham warned, "If it did happen there would be hell to pay," while Senator Benjamin Cardin has threatened to target sanctions at senior Saudi officials.

But Saudi Arabia wears too many hats for America to abandon it easily. Though the US no longer needs Saudi oil, thanks to its shale reserves, it does need the Kingdom to regulate production and thereby stabilise markets. American defence contractors are dependent on the billions the Kingdom spends on military hardware. Intelligence cooperation is crucial to ferreting out jihadists and thwarting their plots. But, most important, Saudi Arabia is the leading Arab bulwark against Iranian expansionism. The Kingdom has supported proxies in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen to contain Iran's machinations. Any steps to hold the Saudis responsible for Khashoggi's death would force the US to assume responsibilities it is far more comfortable outsourcing.

It is a role America has long sought to avoid. When the United Kingdom, the region's colonial master and protector, decided that it could no longer afford such financial burdens, US leaders ruled out taking its place. Policymakers were too focused on Vietnam to contemplate action in another theatre. Instead, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger conceived a policy whereby Iran and Saudi Arabia, backed by unlimited US military hardware, would police the Gulf. While Iran stopped playing its role following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Saudis still do.

It is a quandary Trump seems to grasp. Though he vowed "severe punishment" if the Saudis did indeed kill Khashoggi, he refused to countenance cancelling military contracts, instead lamenting what their loss would mean for American jobs.

It is not only defence contractors who are going to bat for the Saudis. Before Khashoggi became Washington's topic du jour, the Saudis paid about ten lobbying firms no less than USD 759,000 a month to sing their praises in America's halls of power.

But it may be the Saudis' new best friend who will throw them a lifeline. As Iran has become the biggest threat to Israel, the Jewish State has made common cause with the Saudis. Former Saudi bashers such as Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu's confidant Dore Gold now meet with the Kingdom's officials. Following the 2013 military coup that toppled Egypt's democratically elected government, Israeli leaders urged US officials to embrace the generals. They are likely to do the same today if US anti-Saudi sentiment imperils their Iran strategy.

The US-Saudi relationship has been a rocky one, and its setbacks and scandals have mostly played out away from the public eye. Yet it has endured and thrived. This time, too, in the wake of Khashoggi's disappearance, common interests and mutual dependence will almost certainly prevail over the desire to hold the Saudis to the standards expected of other close US allies.

Barak Barfi is a research fellow at New America.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2018.

www.project-syndicate.org

(Exclusive to The Daily Star)

Comments