Can we rebuild the lost trust in law enforcement?

The euphoria of August 5 was marred by incidents of violence including attacks on minorities and supporters of the former government, rampant looting and burning of houses and establishments associated with the Awami League regime. Mobs attacked police and some perished under their wrath; police stations were burnt to the ground. The result was a general feeling of insecurity as police became reluctant to perform their duties, fearing for their safety. In the wake of all the uncertainty and mutual mistrust, how can we come to a state of peace and normalcy?

JYOTIRMOY BARUA

Advocate, Supreme Court of Bangladesh

After the jubilation following the fall of Sheikh Hasina, we saw the horrors of the nights of August 5—how houses were set on fire, vandalised and looted, and no one was prepared for that. For some unknown reasons, the army disappeared from the streets. Whose decision was that, and why was it done? From different individual sources, we heard that the army did not have enough human resources or they were not prepared for the ensuing chaos, but we have not received an explanation from any official sources yet.

Had there been army vehicles in the streets, or if people knew that army platoons were patrolling the streets, then these incidents could have been avoided. The arson attack at the Bangabandhu Memorial on Road 32, and other state institutions, such as the Shishu Academy, could have been avoided. Also, individual attacks, neighbourhood robberies could have been addressed.

As a result, the general public suffered the most and are still suffering. We heard from different Hindu businesses how Jamaat or BNP activists carried out extortion, threatening arson attacks on warehouses with goods worth lakhs of taka. In some places, the business owners tried to manage the situation by giving money to the goons; in other areas, they could not and their houses and businesses were attacked and looted. Well-off Hindu households and even impoverished Hindu families in neighbourhoods were individually targeted only because of their religious identity. In many cases, these families did not even dare to go to the media to report these attacks.

The attacks on some police stations, as well as families of police personnel, have been so severe that many are too afraid to get involved in anything. Because of my personal contact with several police officers, I have tried to find out how they are feeling. A lot of people within the police are traumatised—they need counselling. It is important to find a way to help them get back to work.

But let me be clear: we do not want to see anyone, who has been identified as a perpetrator in the mass killings, involved in any work of the state. It is not enough to merely suspend them for their crimes. It is very important to set an example by trying them and bringing them to book to create public confidence. The previous regimes always ignored these issues.

Not every action performed in uniform, be it of the police or any other security agency, is legal. I want to reiterate that we need to come out of the culture of taking only administrative actions against someone who commits a crime while wearing a police uniform. We need to try such perpetrators under criminal offences just like a layperson is tried. This has to be brought under the purview of our existing laws. If restrictions exist in the current laws, those have to be removed and new provisions for trying law enforcers must be incorporated.

RASHED NIZAM

Crime reporter, Jamuna Television

Our past experiences of covering a conflict or clash did not work this time during the uprising because we did not know where we could stand for safety. Reporting rules require journalists to stay somewhere above the ground or behind the most powerful party in a conflict zone to avoid attacks. This time, we had a totally new experience and had to stay in the middle. Consequently, five journalists were killed during the unrest and we still do not have data on the total number of injured journalists.

After the events (in July and early August), it was the police who were attacked the most. We could not go to Jatrabari, Mohammadpur and Uttara police stations in relation to the incidents that took place on August 5 and after. Nobody knows yet the total number of police fatalities. From August 5 onwards, I received phone calls from many people, especially journalists or friends from minority communities, who asked for confirmation of certain attacks. As a crime reporter, my primary source of confirmation is the police whenever there is a murder or other criminal incident. With no police in sight anywhere for the first few days, who could we call for confirmation?

We could not go to the spot and collect the news ourselves because of fear of attacks. Media outlets, including The Daily Star, quoting two organisations, reported that 205 incidents of communal violence took place in 52 districts, but why could they not follow up on their own? The change in journalism that we had expected in the new country where we would have freedom of expression—I have not seen it yet. For how long will we operate out of fear?

Moving forward, another serious concern is politicisation of the police. There are two organisations for the police: Bangladesh Police Association, which includes personnel from inspectors to all the lower ranks; and Bangladesh Police Service Association which is for BCS cadre police. Suddenly, the latter announced that they were creating a new committee as they could not find members of the previous committee. The person who was named as the main adviser of the committee had been an active official during BNP regime. This is indicative of the same politicisation in police that we have been talking about. What kind of change is really taking place, then?

The police reform programme has not been implemented in Bangladesh for many years, though a lot of money has been spent on it. There was a critical point there about making the police independent. The interim government should start the reform process because a political government will never carry it out.

MAISHA ISLAM MONAMEE

Student of Institute of Business Administration (IBA) at the University of Dhaka

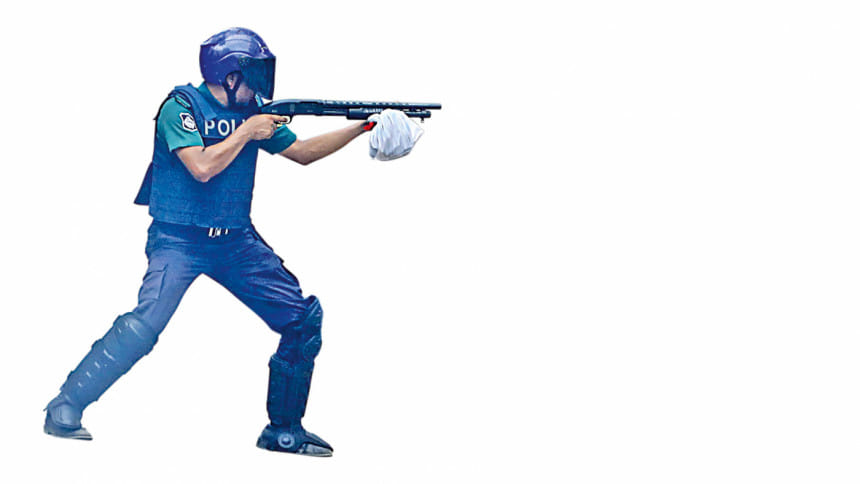

The recent resurfacing of videos and images from the police crackdown during the anti-discrimination student movement has plunged us into a deep reckoning. These records, apparently captured during the internet shutdown, unveil the extent of the brutality unleashed upon innocent protesters—students, civilians, and activists who dared to raise their voices. As we watch the horrific footage of police officers opening fire on unarmed citizens and dumping their dead bodies like sacks, it is impossible to not feel a profound sense of betrayal. The police force, funded by our money, was meant to protect us, not the interests of a ruling party. But in those moments, they became agents of oppression, leaving an entire generation traumatised.

The trauma inflicted by these events runs deep. For many of us, the police are no longer the first responders in times of crisis but are seen as a threat and an instrument of violence that could be turned against us at any moment. This fear is not unfounded—it is born out of real experiences, documented in videos that are now indelibly etched into our collective memory, triggering a visceral response of fear, disgust, and disbelief. The images of bloodied students, the sound of gunfire, and the sight of lifeless bodies have left us questioning whether we can ever trust those who were supposed to protect us.

To understand the depth of this betrayal, we must remember the fundamental role of the police in a democracy. The police are not meant to serve the interests of any political party or government; they are meant to serve the people. Their salaries are paid by taxpayers—by us. It is our money that funds their operations, and it is in our name that they are supposed to act. When the police turn their weapons on the very citizens they are sworn to protect, they are not only betraying their oath but also misusing the resources provided by the people. This breach of trust is egregious because it undermines the very foundation of our society. The rule of law is essential for the functioning of any democracy. When the enforcers of the law become violators of it, the entire system is called into question. How can we, as a society, have faith in the justice system when those responsible for upholding it are seen as perpetrators of violence?

To begin addressing this trauma, there must be a collective acknowledgment of what happened. The interim government must take steps to ensure that the truth is not buried, that the stories of the victims are heard, and that those responsible for the violence are held accountable. This is not just about punishing the perpetrators; it is about sending a message that such actions will not be tolerated, and that the state stands with the people, not against them.

It goes without saying that rebuilding trust in the police force will be a monumental task. The first step must be a complete overhaul of the police force—one that addresses both the structural issues and the culture of impunity that has taken root. This means implementing rigorous accountability measures, ensuring that those who abuse their power are swiftly and publicly punished, and creating mechanisms for independent oversight of police actions. The police must be taught to see themselves not as enforcers of the state's will but as protectors of the people. This shift in mindset is crucial if we are to restore any semblance of trust in the institution.

The trauma, disgust, and fear that we feel today are valid responses to the horrors we have witnessed. But we must channel these emotions into action—into demanding reform, into building a police force that we can trust, and into creating a society where such atrocities can never happen again. It is time to reclaim the police force for the people, to rebuild it into an institution that serves and protects us all.

MOHAMMAD NURUL HUDA

Former Inspector General of Police

Let's first ask: why does the police behave the way it does? Does it operate on its own? No, it does not; it is directed, as it is part of the executive. The question, then, is: can legal action be taken against members of the force who are directed by the executive?

There are some legal protections afforded to law enforcement, which were made during the colonial era. For instance, Section 76 of the Penal Code states: "Nothing is an offence which is done by a person who is, or who by reason of a mistake of fact and not by reason of a mistake of law in good faith believes himself to be, bound by law to do it." Whether to keep this provision is a big question. After the birth of Bangladesh in 1971, a constitution for the People's Republic was formed. But the politicians at the time did not change colonial rules and regulations because they wanted to exercise such power.

The relationship between the police and the public is that of chase and counter-chase. Why is the relationship like this? It all comes down to the mindset of the police who wants to ascend to power any cost—and it's not just one person, it's everyone.

Our constitution is republican but our rules are feudalistic. It is very difficult to defeudalise and decolonise yourself. Heavy words are easy to say but implementation on the ground is very difficult. Public servants must consider themselves as appointed servants of the republic. They need to understand the difference between serving a party and serving the people.

ASHFAQUE NIPUN

Filmmaker

If we are to focus on the events of August 5, one must ask about the role of the army. On one hand, they withdrew the curfew, but then they disappeared from view. Was it really that they did not have enough manpower? We know the characteristics of the Bangladeshi people; they become rule followers as soon as they step into the cantonment. And there was a soft corner amongst the masses regarding the army during the uprising, so it is confusing why they simply allowed such vandalism and violence to take place.

Meanwhile, the distrust that has been created between the people and law enforcement agencies—the police, in particularly—needs to be addressed urgently. Never before have we heard of such widespread attacks on police stations. Many stations in Dhaka were set on fire and police personnel were hanged. Violence begets violence. No matter how much we despise the police, we need them at the end of the day and we need to be afraid of them. The fact that a police station was set on fire means that now the fear is gone. If another incident untoward incident happens after a year, it means a group of 10 people can go and attack a police station because that tendency has been created among us. We need to come out of this.

We are all looking for immediate solutions. But the truth is that real reforms will take a long time. It might not be done even in five years, given the extent of corruption and injustice that was perpetuated over the past 15 years. A huge gap has been created between us and the police, the judges and every single segment of the administration. We do not believe in any investigation. We do not trust any judgements. We believe that all these are hollow words, that nothing will materialise at the end of the day. This trust has to be rebuilt.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments