Independence from tokenism

We often lament, especially on days like our Independence Day, about how little our people (particularly the younger generation, always the younger generation) know about our history. We talk about how people conflate the day with the Language Movement, or Victory Day. We talk about how the sacrifices of the martyrs have not been duly appreciated. Sometimes, we share stories of freedom fighters living in wretched conditions. Sometimes, we share a picture of a farmer in a jute hat, carrying a gun, fighting that war, on our social media profiles.

All this confusion, even though all we have to do is turn on a local television channel, any time of the year, to find at least a few talk shows or programmes being dedicated to the freedom fighters of our nation, invoking chetona of the War of Independence, Muktijudhho, lamenting the loss of lives, and the human cost of war.

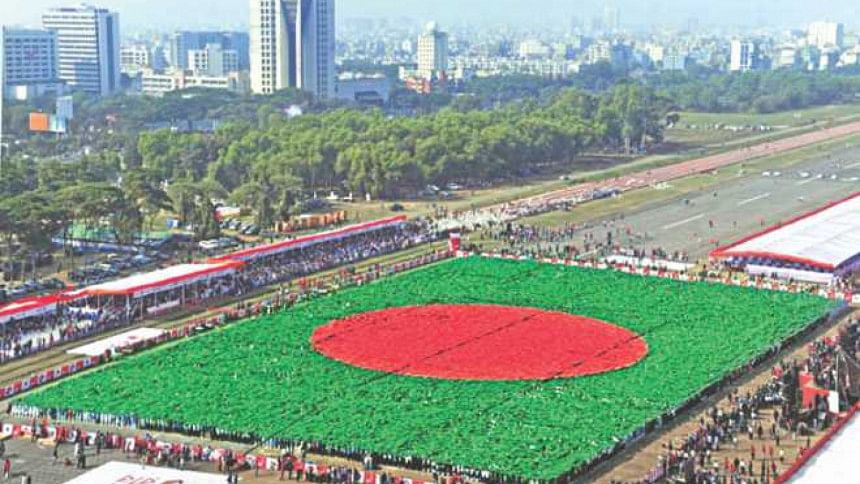

We are frequently exposed to advertisements that invoke ideas of nationalism via flag waving demonstrations that are meant to be patriotic. We even participated in a "human flag" competition for a couple of years, thanks to a telecom company's mission of becoming a household name. I have even found myself at conferences where presentations include sections where presenters bring up the War of Independence, revisiting the violence and the death toll, even when their work is not even tangentially related to this history.

But even then why do so many people have so much confusion about what happened when?

Maybe it's because of all this, I propose.

Maybe because we are exposed to snippets of history from political leaders, but not from historians.

We hear personal stories of violence and trauma, but never a systematic review of the events that led to the War of Liberation.

We hear about our leaders, about individual men (never women) without whom we would never be independent from Pakistan, but rarely about the ordinary men and women without whom nothing would have been possible.

Maybe we are confused because when we think of our history, we think of 1971 as the beginning of Bangladesh, ignoring everything that we had been a part of before then.

We forget that we have had various forms of struggle for independence for decades, starting with, for example, the 1906 separation between East and West Bengal to the Language Movement in 1952. We forget the formation of Bengali Liberation Front in 1958. We forget that economic disparity between East and West Pakistan only deepened when East Pakistan was hit by a cyclone in November 1970. We forget the Agartala Conspiracy Case. We forget that Sarbadaliya Chhatra Sangram Parishad in 1969 were the first ones to shout Joy Bangla instead of Pakistan Zindabaad. We forget that Awami League won 288 of the 300 seats in the East Pakistan Legislature. We forget that the National Assembly that was to be held in Dhaka on March 3 1971 never took place because Yahya Khan cancelled it. We forget that independence does not only equal to national state sovereignty.

Instead of discourse, what we see and hear around us is tokenism.

And, tokenism creates disparity. Because it makes us feel like we're doing something (about something) when we're not.

In this case, tokenism creates the illusion that we know our history, creating a disparity between actual history and stories that are repeated in the name of history. These stories have no real meaning, no real information, but consist of emotional language and gory details. These stories give us the impression that we know our history.

An example is the term "muktijudhher chetona" and all the stories that go along with those two words. These two words are repeated ad nauseam by anyone who wants to make an impression on the ruling party, which means we hear these words without context. We hear these words as indicators of party affiliation. Which means these words lose meaning as they are co-opted by sycophants and the like.

So as we step into our 46th year of independence from Pakistan, let us make a few demands. Free country, after all:

We don't need or want to hear about any kind of chetona from every person who wants to impress the ruling power heads. We need to hear about the history from those who partook in the War, and historians who have analysed that history.

We don't need or want to hear about the nine-month war from celebrities who themselves have half-baked ideas about it – we need to read about them in our textbooks, our history books, alongside everything else we should be learning in school. This means we need to keep our textbooks apolitical, i.e. beyond the reach of party politics.

We need to stop treating ourselves as victims of Pakistan's oppression. Because we won that war, even if Pakistan claims it was an India-Pakistan war, even if they don't apologise for it. We got what we wanted, albeit at high cost. We can forgive, for our sake. Because we can. Because that's the right thing to do.

This means we need to stop acting like Pakistan is our enemy for life. We know, too well, perhaps, that life is short. Too short. For grudges. For anger. For regret. We need to start living, start enjoying this hard-earned independence.

Let us own our history. The history of the People's Republic of Bangladesh should be owned and written by the people of the nation and historians who study this history. Not its political leaders with vested interests. Not sycophants of government in exchange for real or perceived political gain. The people.

But, to be truly independent means to not regurgitate ultra-nationalistic tropes to oppress other groups. If we are to learn anything from our history, it should be this: that by marginalising our minority groups we can only become our own oppressors.

When we as a people, who fought for our own self-determination, stop behaving like the oppressor state that we freed ourselves from, and bring into our discourses, laws, syllabi, institutions, and legalese the rights, the self-determination of the minority peoples, and their languages, will we truly understand independence, and truly be independent.

The writer is Assistant Professor, School of Social Work, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments