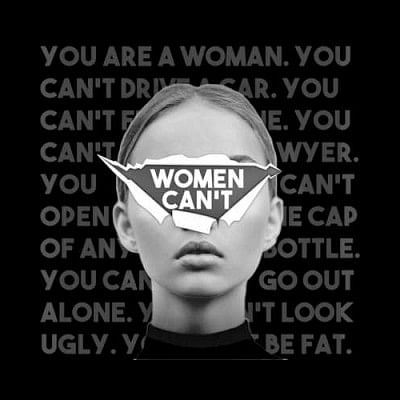

Spot the patriarchy

Last year I attended a talk where the mayor of Dhaka North was a speaker. I had asked him a question. He responded. After the talk he asked me what I do. I gave him my credentials: Assistant Professor at University at Buffalo. A woman standing next to him during this exchange—an acquaintance I know socially—quipped: Oh, teaching assistant? How sweet! I said no, and repeated my credentials. I would have said more if I could gather my wits that quickly. Or not. I still can't think of an appropriate response.

What do you do when someone infantilises you because you're a young(ish) woman? There were men in that room with the same credentials as I. Did anyone ask them if they were teaching assistants? Of course not. To make things worse, someone actually advised me to take that as a compliment, reminding me how we let them get away with everyday misogyny (or internalised misogyny) by pretending that they perhaps had good intentions. That's rubbish—I had said, invoking our esteemed finance minister—I'm not buying that.

A friend, a woman, recently told me, that her boss—not a woman—sent their team an email saying that she was struggling and needed help. When she told him that she wasn't struggling but merely had a few questions, he responded, his tone almost paternalistic, as if he was looking out for her, helping the proverbial damsel in distress: Aharay, mind korechho? (Poor thing! Did you mind?)

Another friend, another woman, got a raise recently. But, she was asked to not tell her senior male colleagues about it because it would upset them. Why? One might ask. Because these men have benefited from male privilege for so long that when women get raises it upsets (at least some of) them. So much so that even the administration knows about it, and plays along, speaking to how entrenched patriarchy is. Not to diminish all men; many men are feminists, and allies of women and other oppressed groups (indeed, we need men as allies, because it's not always easy or safe for women to speak about their experiences). But, unfortunately, far too many men are not.

We know this because these stories of working women navigating patriarchy and patriarchal norms are neither new nor unexpected. We know this because these stories are not from my grandmother's time but happening now, in 2017. What, perhaps, is new is that some institutions are at least attempting to navigate the patriarchal system, but it's a drop in the ocean.

Let me elaborate with an example.

Much of my academic work is on structural and social problems. What I've realised over the years, as I've studied institutions, is that we are often made to take personal responsibility for structural problems, even though there are no individual solutions to begin with. But, that's the mantra of neoliberal institutions. They "responsibilise" the citizenry, create consumers out of them, and tell them that they can buy their way out of social problems—be good citizens by being good consumers.

An example: climate change.

A solution that we are often given: washing clothes with cold-water setting (instead of hot) on our washing machines. This is in line with global messages about going "green." I want a green earth. But, I'm not buying this solution. Why? You might ask. Because, using cold water will not significantly reduce the carbon footprint of the world. The irony is that much of the carbon footprint comes from factories like the ones that produce these washing machines in the first place. So, by responsibilising me they get me to buy a washing machine, and associated upgrades that promote efficiency, and in return I feel altruistic, dutiful, as if I'm saving the world. Only, I am not.

This is symptomatic of the problem of patriarchy, and the solutions that claim to "smash the patriarchy." The solutions are welcome, but they often seem like lip service. When an organisation recognises the labour of women, gives them raises, but keeps it hush-hush, they are basically just buying the washing machine and feeling good about themselves. They are not actually changing social norms that support the subjugation of women, or challenging those that support the gender wage-gap.

When empowerment programmes provide skills training for women to help them find employment, they help the women individually. However, these initiatives don't change cultural norms that trivialise the problem of sexual harassment at work and on the streets. They prepare women to enter the labour market, but do nothing about men who are somehow always surprised by it, and too often they take women's work as a sign that women are promiscuous, easy, available. In doing so, these empowerment organisations inadvertently contribute to victim-blaming narratives of sexual harassment by putting women in places without making those places safe for them, by not doing enough to change the conversation about sexual harassment.

This is akin to paternalistic bosses patronising women employees in the name of "help" but do not affect meaningful change within the organisation that could help women. There is no understanding that the so-called "help" can potentially put their employees at risk of experiencing other forms of distress; that they might be perceived as inefficient or under/unqualified.

Then there are those women who have internalised misogyny—they look down on other women. They claim they don't get along with other women. They echo tropes like "women are other women's worst enemies." They slut-shame. They blame women for their problems. They think women are not as smart or qualified as men. They demean or infantilise other women to feel superior. They deprecate the word "feminist." This is not an exhaustive list, but you get the drift.

Part of the reason why women may internalise misogyny is simple: it's everywhere, it's the hegemon, it's how social and family life is ordered and structured. Some women have found ways to benefit from patriarchy, in the way of navigating the system by using the system. But, it's problematic when their stance is absolutely anti-women. Women who are in the business of trafficking women come to mind. Women who beat their housemaids come to mind. Women who defend the beating of housemaids come to mind. As does the woman who thought it appropriate to question my credentials because I don't fit the profile of a typical professor.

What becomes clear is that patriarchy affects everyone across class and social barriers. Patriarchy is not just a feminist's problem, it's everyone's problem. Patriarchy is in the business of controlling and maintaining control over women in all spheres of life. Most men deny its existence because they benefit from it. (But men, too, suffer in systems like this, because patriarchy is also in the business of creating toxic masculinity of which many men become victims. More on this on a different day.) In some countries it's a little less overt than others; in some countries it's a little more sophisticated than we are used to seeing.

Patriarchy is like water; it flows into all the systems—from religion to governments to educational institutions to businesses. Ergo, it becomes important to spot patriarchy in its many guises. Maybe a tech startup can design and develop a game: Spot the Patriarchy.

Nadine Shaanta Murshid is Assistant Professor, School of Social Work, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Comments