Expanding the frontiers of connectivity

Recently, Facebook membership crossed the two billion mark, making it the leading social media platform in cyberspace. For more than a decade Facebook has made sure we know what our friends' babies look like, what our high school classmates think about politics or what kind of music is popular with our peers. At a personal level, it has made each one of us "newsworthy" by enabling us to showcase our private lives in the public arena. Over time the Network has evolved, broadening its reach to rally support for protest movements like the Arab Spring, for generating pressure on industry giants to act ethically and to build a broad consensus on critical social issues.

One would think these are path-breaking achievements. However, Facebook's CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, believes that connecting people online is not enough. In a CNN interview he noted that "it's important to give people a voice, to get a diversity of opinions out there, but on top of that, you also need to do this work of building common ground so that way we can all move forward together." Consequently, the company revised its mission statement: "To give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together." The new tool for achieving this objective is Facebook Groups. Creating a Group in Facebook for a specific cause is likely to generate synergies far beyond the random conversations that take place between friends and acquaintances. The idea, it seems, is to establish a market place of common interests amongst users. This is especially significant at a time when trust in institutions, experts and leaders is at its nadir. People have more faith in their peers who are familiar with their problems and are thus more likely to be guided by them. Since Facebook is free it provides its users a level playing field with forces that can pay to lobby for their goals.

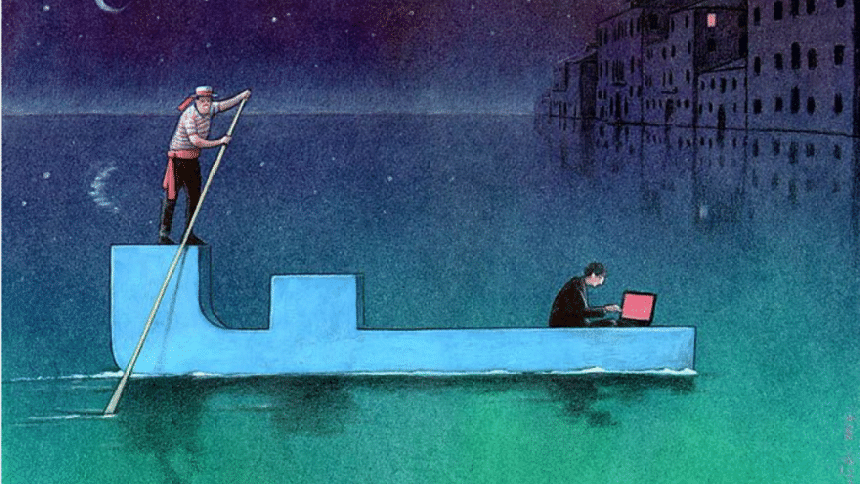

The change in thinking, away from casual and mundane interactions for entertainment, in favour of purposeful and empowering communications for better understanding of issues is not only confined to the social media. It has also permeated into the world of fiction writing and creative arts. Recently, I happened to be at Arundhati Roy's book launch hosted by the "Politics and Prose" bookstore in Washington DC. When asked why she had waited two decades to publish her second novel, Roy's response was that it's not important to produce just a novel — there must be a purpose to even fiction writing. She expanded this idea in an interview: "It's not about imparting information, that's not what a novel is…For example, you can't explain just in evidence and footnotes and human rights reports the fear and terror that is in the air of Kashmir, what it means to people to have to live with this terror day and night, what a military occupation of 20 years becomes, when it seeps into the cellular structure of social life there. I think fiction can address it in ways that straightforward reportage cannot." Just as Zuckerberg aims to bring communities together through Facebook groups, Roy describes her fictional writing as: "A way of binding together worlds that have been ripped apart."

One could argue that it's unrealistic to expect that by connecting people through Facebook or by narrating stories about pain and suffering, hate and vitriol can be eliminated by love and acceptance. However, the shift toward defining a clear set of goals for our leisure activities, addresses a much broader question: should our idle mental pursuits have a "higher" purpose? Is it kosher to indulge in activities like interacting on Facebook, reading a novel or listening to music merely for pleasure? Many would say: "Why not? The realities of life are so overwhelmingly stressful that occasionally one does want to escape into the virtual world of Facebook or the surreal setting of a novel or a piece of art. The so called mindless pursuits make us happy, just like good wine or gourmet food."

The debate about "art for hedonistic pleasure or art for a greater cause" is ongoing and will continue. But there is broad consensus on one issue: a good work of art can connect you to your senses, not just your mind. In our fragmented world, it's important for people not only to comprehend adversity with their minds, but also to feel it emotionally and spiritually. This might motivate some of us to turn compassionate thinking into compassionate actions!

The jury is still out on the usefulness of activities that give us undiluted pleasure without a definitive purpose. However, here's my parting thought: By making citizens feel a part of the greater human family, by connecting people or "cyber tribes", Facebook, novels or any form of creative art can have a worthwhile impact on a divisive, untrusting, unstable and unpredictable world. I, for one, wait with bated breath to see if Zuckerberg's social revolution will indeed help generate more cohesiveness among people.

The writer is a renowned Rabindra Sangeet exponent and a former employee of the World Bank.

Comments