Confessions of a madrasah student

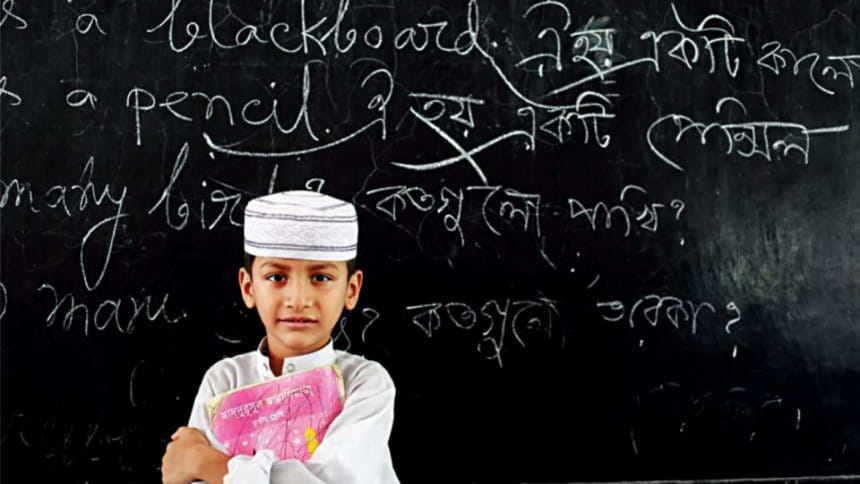

You can't help it. You see us from afar—our messy beard, unkempt appearance, the distinct attire that sets us apart from others. With our straight-cut panjabi falling well below the knees, loose-fitting paijama, and a skullcap straight from history books, we remind you of the other side of progress.

You tend to cringe if we come closer. You think twice before being in the same room as we are, because of who we are. Perhaps you are afraid of us. Perhaps we don't smell as good as you do. Your children, too exhausted by their books and video games to be imaginative, think we probably live in some other world.

You can't make sense of why we do what we do. We are still into ancient texts and scriptures that have no real-life applications. Utterly pointless, you decide. Our teachers, whose interpretation of life defies all logic known to you, are the intellectual antiheroes, preaching blind faith and whatnot.

And as we grow, you worry we might turn into a dark force and take the world back to its primitive days. You don't understand us really—us, the students of madrasah.

***

Before anyone begins to wonder: this is how the madrasah students, by and large, are made to feel about their way of life because of the constant scrutiny, misconceptions and stereotyping by a certain group of people in society—people whose action or inaction, unfortunately, plays a role in their life.

I know this from my own experience as someone who has spent a significant part of his life in a seminary. I grew up in a neighbourhood not far from Dhaka, in a residential madrasah that combined general subjects with the Islamic ones so that its students could have knowledge of both. I was an eight-year-old when I first went there.

Soon I was confronted by what was the beginning of a prolonged identity crisis. Who am I? Why do people look at me the way they do? Am I different? I was still too young to understand the debate on public education reforms but I was beginning to get the point: I was not like others. Others whose life followed a more linear, accepted course than mine. I walked through the streets with the pain of being singled out. I once saw a friend cry because he was denied entry to a cinema, because of his attire, and another left the madrasah for good because he couldn't stand the stigma attached to it.

As I look back now, after over a decade since I left that life, I still remember the look of pity and disdain. The awkwardness of being the "other". I find myself secretly relishing the decision to move out. For nothing has changed in these past years to think that our society has learned to accept diversity.

***

On July 8, police captured Sohel Mahfuz, a terrorist linked to the banned Jama'atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), in Chapainawabganj. Sohel, a key suspect in last year's Holey Artisan attack who specialises in explosives and covert communications, had been eluding capture for over a decade.

Before he left home in 2003 to fight for his newfound cause, Sohel Mahfuz, originally Hasan Sheikh, was a student of a village madrasah in Kushtia. That was 14 years ago. He went on to become a most wanted terrorist in Bangladesh and India. Soon after his arrest, several newspapers found it necessary to give his educational background a special mention, in their headlines or intros, as if that was a contributing factor. Some social media pundits are even using it to stoke the old debate on the susceptibility of madrasah students to terrorism.

There is, evidently, an obsession with madrasahs' supposed link to terrorism in some quarters. This is partly due to the cloud of mystery that hangs over this community, which is still largely isolated and underrepresented, and the fact that there is no central authority to clear up confusions in the public mind. Further aggravating the situation is a small but powerful faction within the community that wants to impose its own theo-fascist variety of Islam over all others.

But if the Gulshan café attack is any indication, the seed of terrorism can be sown anywhere—in the affluent section of society, in shanties, in English-medium schools, universities, and yes, in madrasah, too—if "proper" motivation can be given. Terrorism, however, is not the only problem that dogs the general madrasah students.

***

Since my childhood, I have always loved reading books. I remember reading classics, thrillers and romance novels in between classes, and in the wee hours when everyone else was waking up for their morning prayer. I went on to pursue a higher degree in literature after I left my madrasah, Tahfizul Quranil Karim Fazil Madrasah, a liberal institution that promoted a healthy combination of classroom education and extramural activities.

I know quite a few madrasahs that, while following the course curricula set by Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board, encourage their students to go through physical and life-skill exercises meant to make them decent, productive human beings. I do not claim to know all the madrasahs, however, nor is whitewashing the system or its murky past the goal of this column.

Loopholes do exist and "no idea can be above scrutiny, just as no people should be beneath dignity," as the British activist Maajid Nawaz has said. My immediate concern is the endless stereotyping of a community that is perhaps as diverse as any other, which makes any reconciliatory attempt futile.

***

There are lakhs of students involved with the madrasah education system. This sheer number alone makes a statement that's hard to overlook: that you can't ignore them. The subtle tension and faceoff that exist between this group of students and the rest of the society—especially its educated elite—are unfortunate, to say the least, and damaging to the interests of both.

Since I have had the opportunity to see things from both ends, I can't help but feel that our society needs to open up a little more to these children, their teachers and their way of life. Whatever reformation is needed in the system should be in their best interests, preserving its unique quality as a medium of Islamic education.

Misconceptions occur when there is a miscommunication. Miscommunication occurs when there is a lack of understanding. We can't hope to be a united nation unless we reverse this cycle, and start trying to understand each other, our humanness and our differences, and reach out to each other instead of staying away.

The social and cultural "othering" that madrasah students are subjected to far predates the rise of terrorism in Bangladesh, but it may presage an even more frightening prospect for us in the future if it is allowed to continue. What's important to remember is that those involved with the madrasah system yearn for acceptance as much as anyone else.

Badiuzzaman Bay is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments