Achieving SDGs and reducing urban poverty together

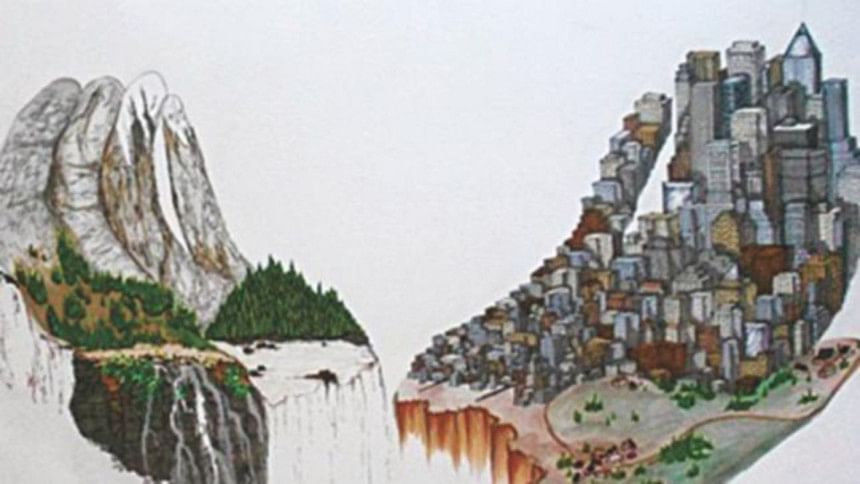

Bangladesh has performed significantly well in attaining the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) compared to many other countries in the world. But over the last couple of decades, the country has undergone rapid and massive urbanisation—where currently 37 percent of the total population live in urban areas of which one third (around 2.4 crore) of people live in the squalor of slums, and this figure is expected to increase to around 4.5 crore by 2030.

In pursuit of upholding the progress made to attain the MDGs to be sustained for SDGs as well, SDG 11 highlights the importance of making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe and resilient. In order to deal with the challenges of urban poverty, Bangladesh has to fulfil other major goals including SDG 1, 2, 3 4, 5, 6, 10 and 13 that focus on other pertinent issues such as hunger, health, education, employment opportunities and others in the urban areas which essentially indicate that there is an innate connection between all SDGs in pursuing sustainable and inclusive urbanisation of the country.

Urbanisation is identified as both a cause and a consequence of economic growth. The concept of urbanisation has been identified to be as such that it is an irreversible and robust process that is interlinked with socio-economic changes. In Bangladesh, the rate of growth in urban areas is at a staggering value of four percent annually, which happens to be more than 2.5 times the rate of growth in the rural areas. One outcome of this is that rural-to-urban migration is taking place at a higher rate which is further aggregated by climate change—both slow-onset events like increasing temperature and sea level rise, salinity intrusion as well as sudden onset events like cyclones and storm surges. The global scientific community has said that due to climate change, the frequency and intensity of extreme events increase.

Deniers can raise doubt about the facts related to climate change and even question the correlation between climate change and disaster risks. But the harsh reality is that we cannot be ignorant of the aftermaths of the extreme events—like hundreds and thousands of people being affected by river erosions, which is an annual occurrence, causing heavy losses and forcing people to migrate to urban areas. Considering this, it can be projected that the number of the urban poor will soon exceed the number of the rural poor. Poverty anywhere in Bangladesh will be a major threat and obstacle in achieving the SDGs. Thus, it is overwhelmingly clear that special attention is required to address the concerns of urban poverty.

A major proportion of the population is still spread around in the rural areas of Bangladesh and there is no reason not to prioritise and think of ways to work on rural development or rural poverty reduction. In Bangladesh, there are many who have negative views about urban development as well as urban poverty reduction because they believe that urban development is a competitor to rural development; it is believed that village-to-city migration is an impedance towards development and should be reversed along with the thought that slum improvement and urban poverty reduction programmes will be acting to pull more people to the cities.

Several past governments initiated numerous programmes aiming to pull back the urban poor to their rural origin. But in reality, the situation of urban poverty remains unchanged and even their numbers have been constantly been on the rise. The urban planning and service providing authorities usually treat the slum population as illegal occupants of the city and, as a result, the poor urban settlements often remain invisible and even their basic needs remain unfulfilled.

We can observe in the status quo that several urban poverty reduction projects and programmes have already been implemented by a few of the government agencies and several NGOs with financing from both government and development partners since the mid-1980s. Major lessons learnt from these projects are that for developing and implementing any urban poverty reduction programme, the urban poor themselves should be put in the driving seat. The evidence shows that the urban poor are in fact active and creative; they are dynamic agents of change and it has been observed that wherever they have been empowered to carry out a task, they have proven their ability to identify, prioritise and plan to solve issues on their own, by valiantly participating in the execution and steering of measures for their own improvements. The new generation of urban poverty reduction initiatives should be built on the basis of the lessons learnt, should focus more on security of land tenure and housing solutions and not be isolated from pathways to sustainable urbanisation.

Efficient urban poverty reduction does not only require the clear understanding of the multidimensionality and comprehensiveness of urban poverty, but also the complexities of the urban system. Achieving the goal of urban poverty reduction requires effective urban planning and management practice that is properly equipped and provides decisive powers over the allocation of funds. Otherwise, sustainable and inclusive urbanisation will remain a dream and will never materialise.

Achieving the SDGs requires the taking of responsibility by everyone and thus SDG 17 is exclusively formulated to emphasise that there should be strong collaboration and partnership between parties. Thus different political parties, government agencies, academics etc. should focus on this to bring about meaningful change that would help reduce urban poverty.

SM Mehedi Ahsan is an Urban Planner, currently serving as the President of Khulna University Planners' Alumni, and is an Honorary Member, Central Advisory Council to the Center for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighborhood (SHLC), University of Glasgow, United Kingdom.z

Comments