Question paper leaks: A symptom of a worse disease

It's that time of the year again, the season traditionally known for weddings and pitthas. But seasons undergo changes, and the winter can barely live up to its name anymore. And with that we should reconsider what things we associate with this time—a phenomenon that truly characterises this winter. I propose that the winter of 2017 be remembered as the season of question paper leaks, given the almost daily reports this month, sparing no grade, starting from class I.

Are question papers leaks a novelty then? Well, according to a study by Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), the trend can be traced as far back as the SSC exam of 1979. And from then, it has only increased, and today it threatens to engulf the entire education system. So, maybe, commemorating our winters for these leaks might lead to actually acknowledging the problem. Maybe then we will finally realise that outright denials or sporadic threats will not be enough to deter those leaking and disseminating exam questions.

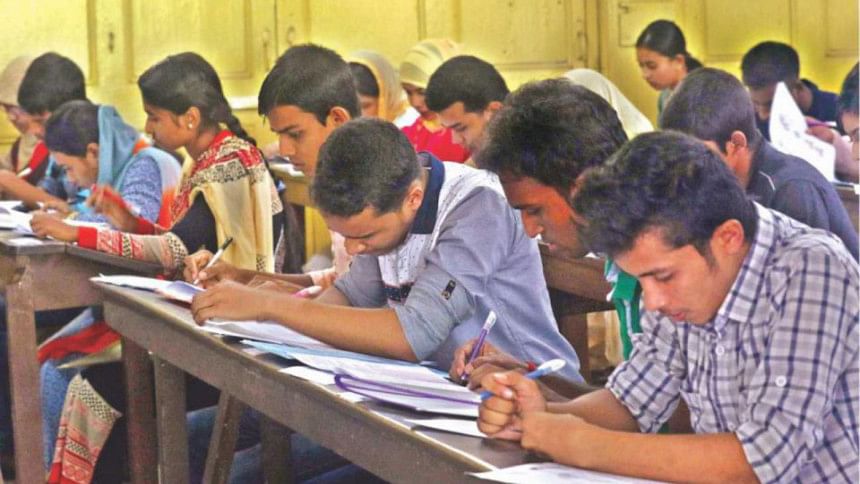

For those unaware of why I feel that this issue warrants importance now, here's a list of the instances of question paper leaks I found through only a cursory look at this month's newspapers. December 13: We reported that in Munshiganj all examinations in 119 schools had to be cancelled following leaks of questions for classes II-IV. December 14: Following leaks of questions each of classes I and V, final exams of one subject each were cancelled in 248 schools in Barguna. December 19: In Natore this time, the maths final exam of 123 schools had to be suspended. Gone are the days when question leaks meant SSC, HSC or university admission exams. What lows have we sunk to, if someone thinks that they can now make money from leaking questions for primary school students? What next? Leaking of viva questions for kindergarten enrolment? For those who forgot, the higher levels are already swamped with similar allegations. In October this year, University of Dhaka authorities, when asked about the allegations of the leaking of question papers of D unit admission exam, outright denied it. Questions for some subjects of this year's SSC and HSC exams too were widely circulated—in some cases even openly on Facebook.

The situation is so bad that the Anti-Corruption Commission last week sent a letter to the cabinet to step up efforts for stopping corruption in the education sector. That, and the conscientious parents who pointed out the leaks to the authorities has seen some results. In Munshiganj, nine have been arrested. There have been some arrests too of individuals linked to leaking of DU university admission questions in 2015 and 2016. Ironically, one such recent arrest is of an assistant director at Bangladesh Krira Shikkha Protisthan (BKSP), allegedly a mastermind of a question paper leaking gang, who himself got the government job because of his "connections". All this brings me to the conclusion that question paper leaks and their growing prevalence is not merely a problem but a symptom of a bigger issue with our educational environment. And worse, the intellectual crippling of an entire generation is yet to come.

What the wise parents who pointed out to the authorities when questions were leaked in the recent cases did is not the established practice. The TIB study mentioned earlier found unhealthy competition among and in schools to be one of the major reasons behind the phenomenon of question leaks. Our entire education system today is based on securing top marks at any cost and parents are rightly worried; missing out might mean a bleak future for their wards. This explains the mushrooming of coaching centres, the ubiquity of the supposedly banned guide books in the market and of course spending money to buy question papers. To quote one parent of a JSC examinee from a report in a daily newspaper, "We understand this is wrong. But our children are not that mature; they exasperate us if we prohibit them from obtaining those questions." And the pressure on children studying for their exams is even more as one could imagine, knowing that their peers might be getting an unfair edge over them. The same report quoted a student saying: "We cannot concentrate on our study without having those questions provided with answers which can be obtained only at Tk 500."

So what brought us here? For one, our education system is now a matter of prestige, where anything other than a "golden" GPA 5 or a background in science is shameful. Our questions are based on testing the memorisation power of students, and the creative questions which were supposed to be the solution, only created a new form of memorisation because of untrained teachers. It is far easier for students and teachers if the "creative" questions are selected from a pool widely available of course. Today, students from grades I onwards spend entire days running from one coaching centre to another. This of course is perpetuated by the school's failing to ensure their fundamental duty: providing the education needed at school. Teachers are without incentive to do their jobs while parents care only about the grades. At the university admissions level—let us take the example of D unit of DU—the questions are so focussed on a student's ability to memorise information, which they can easily look up when needed, that students are willing to do anything to get a coveted seat. On top of that, standardised exams at levels such as grades V and VIII encourage students to study not for learning but for securing grades. And then there is the farce of our textbooks—bland, riddled with inaccuracies and, as the events of this year showed, probably changing for the worse. So, blaming a few "corrupt teachers" for question leaks simply will not do when our entire education system is corrupt and built towards obtaining a prestigious grade.

During my SSCs I remember a fellow student being berated by parents of other students because he refused to pay the Tk 200 to invigilators of practical exams at our exam centre because they thought that him not paying could mean wrath on the entire batch. This is the situation that we have come to, when parents can actually berate students for not being corrupt. During my HSCs, one could study a handful of past-years' questions, not for practice, but knowing that among those say 20, 15 would be set in the final questions.

The ACC has pointed out, as has TIB in the past, the sources of our question leaks: namely the education board, BG Press, treasury and exam centres. They have given recommendations on how to tackle the issue such as greater oversight, digitalisation, separation of duties of question preparation and invigilation, checking if any of those involved have children sitting for exams that year. These are important. With that, I would like to add, what we need to fix too is the demand side of things—that students and parents opt for obtaining these questions knowing that it is wrong. And for that, we need to rethink our education system, from the training of teachers to how they teach in classrooms. Without that, we may put an end to leaks with great oversight, but education will continue to be about getting into a good university and a secure livelihood. These are important and realistic considerations of course, but if someone goes through almost 20 years of education without learning to distinguish and act on considerations of right and wrong, to love learning for its sake or without a basic sense of integrity, then where are we headed? Or are we there already, when one hears of university teachers scuffling with students, after almost a decade of corporal punishment being banned, teachers refuse to follow the law, and students beat up teachers after becoming president of a student body of a political party.

Moyukh Mahtab is a member of the editorial team, The Daily Star.

Comments