The Mountbatten factor in India’s partition

It can be said without any fear of contradiction that one of history's most massive displacements of population with the attendant violence and misery took place when, in 1947, the Indian subcontinent was partitioned along communal lines, resulting in the creation of two independent states: India and Pakistan. Despite the passing of seventy-four years since then, the debate on the justification of the partition continues, and perhaps will go on for an indefinite period, largely due to the deep wounds caused to so many people who were uprooted from their hearth and home.

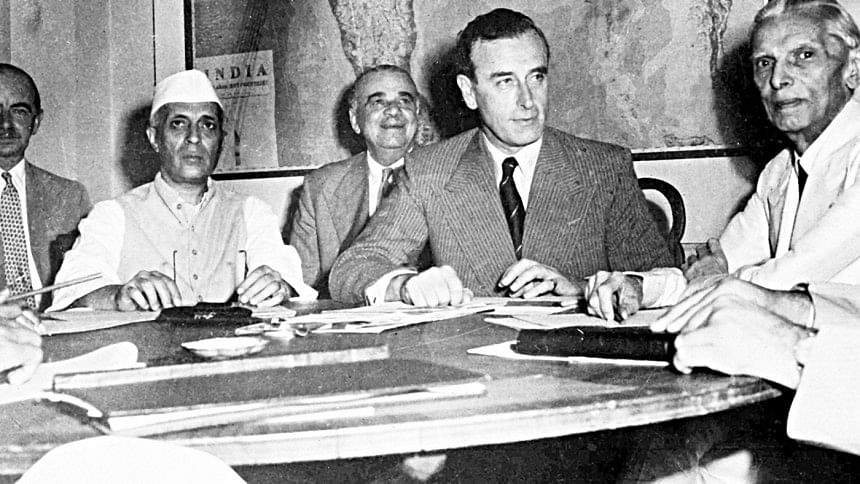

A question arises as to whether India's last Viceroy's "forced march" to the demission of power further heightened communal tension and made partition inevitable and tragic. It would be relevant to recall that British Prime Minister Clement Attlee on February 28, 1947 declared that power would be transferred by June 1948 to such an authority or in such a way as would seem most reasonable and be in the best interests of the Indian people. Mountbatten arrived in New Delhi on March 22, 1947 with plenipotentiary powers and a clear mandate to expedite the process of British withdrawal. Therefore, when the Viceroy on June 3, 1947 announced his new plan and proposed to advance the date of transfer of power from June 1948 to August 15, 1947, the "forced march" began with disastrous consequences.

So why was Lord Mountbatten in a hurry? Recent revelations indicate that "it was his intention to rush back to the fleet as soon he could extricate himself from India and to vindicate his father's reputation". His father, the "First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy, Prince Louis of Battenberg, was forced by London's fierce anti-German prejudice during World War I to abandon the fleet over which he had once so proudly presided. His then fourteen-year-old son resolved to join the Navy himself and remain in it until he became the First Sea Lord".

It would not be inappropriate to observe that Lord Mountbatten had already decided to make fast work of his India assignment. Interestingly, although the British cabinet gave him eighteen months to complete the job, he never had any intention of taking so long. To many experienced British administrators who had earlier served in India, even the eighteen months' time was an unduly hurried process which—if not reconsidered and its early terminal date not pushed back—would cause severe ruination of Indian regions and communities. The new Viceroy, however, was so eager to get on with the job that he would cut the all-too-brief allotment of time in half.

Even Winston Churchill, who was not favourably disposed to India's freedom, commented in the British Parliament that "the government, by their fourteen months' time limit, have put an end to all prospect of Indian unity … How can one suppose that the thousand-year gulf which yawns between Muslim and Hindu will be bridged in fourteen months? … It is astounding." He called the time limit a "kind of guillotine". He further added that, "Will it not be a terrible disgrace to our name and record if, after 14 months' time limit, we allow one fifth of the population of the globe ... to fall into chaos and carnage? Would it not be a world crime ... that would stain ... our good name forever?" However, the quit-India-quickly policy won the House of Commons vote by 337 to 185.

While the complexity of subcontinental politics, intransigence of the politicians, and personal ambitions of certain important political leaders—as well as the divide-and-rule policy of the British establishment—impacted the process of transfer of power, it has to be noted that none of those played as tragic or central a role as did Mountbatten. He had been largely responsible for the "tragedy of partition and its aftermath of slaughter and ceaseless pain".

The rush for partition resulted in the horrid plight of ten million desperate refugees over Northern India. "Hindus and Sikhs rushed to leave ancestral homes in newly created Pakistan, Muslims fled in panic out of India. Each sought shelter in next door's dominion. Estimates vary as to the number who expired or were murdered before ever reaching their promised land. A conservative statistic is 200,000; a more realistic total, at least one million". The tragedy occurred as the last Viceroy did not have the wisdom and patience necessary to accomplish a delicate task. Additionally, he did not have the humility or good sense to appreciate the wise counsels of Indian leaders who "tried their frail best to warn him to stop the runaway juggernaut to partition before it was too late". Mountbatten's negativity towards Jinnah, and its tragic significance for all of South Asia in the aftermath of partition, has been traced from the recent study of transfer of power documents.

Partition maps, revealing the butchered boundary lines, were kept under lock and key on Mountbatten's orders. Had this not been so secret, then the governors of Punjab and Bengal could have saved countless refugee lives by dispatching troops and trains to "what soon became lines of fire and blood", but Mountbatten had decided to wait until "Independence Day festivities were all over, the flash bulb photos all shot and transmitted worldwide…"

"Only in the desperate days and weeks after the celebrations of mid-August did the horrors of partition's impact begin to emerge. No Viceregal time had been wasted in planning for the feeding and housing and medical needs of ten million refugees."

Muhammad Nurul Huda is a former IGP of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments