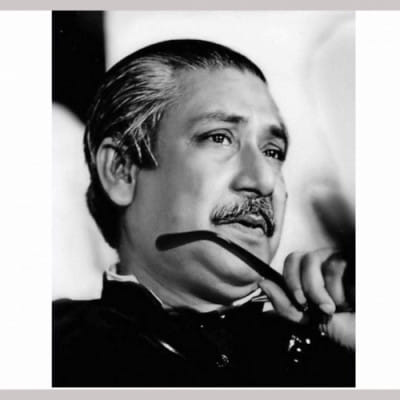

Understanding the greatness of Bangabandhu

While remembering the tragic incident of August 15 1975, we have to agree with the undeniable fact of history that Bangabandhu became a symbol in his own lifetime. He very manifestly personified Bengali nationalism, just as Gamal Abdul Nasser personified Arab nationalism. His charisma was all-pervasive and he became a household name in every village of Bangladesh. He succeeded in articulating the basic emotions which put him at his pinnacle. History singled him out to lead Bengal's struggle to complete emancipation.

The greatness of Bangabandhu can be adequately and realistically understood and appreciated if we correctly grasp the then socio-political situation of East Pakistan, the plight of Bangalis therein and how amidst huge adversity, the battle for complete emancipation had to be fought. It would be relevant to recall that the historic Lahore Resolution, in constitutional terms, demanded regional autonomy for the two Muslim majority, geographically and administratively delineated, areas.

The Lahore Resolution of 1940 had, in effect, sought regional autonomy and definitely not religious autonomy for the Muslims. This demand for autonomy remained the central driving force of the politics of the Bangalis throughout its incorporation in the Pakistan State. In that scenario, Bangabandhu was always at the forefront, forcefully advocating the cause of autonomy. He realised, quite correctly, that the commitment for regional self-rule, had been usurped by the central government of Pakistan. For him, in practical terms, it meant the exercise of central power by a non-Bangali dominated ruling elite drawn from the feudal classes of West Pakistan, allied with a military and bureaucratic elite where Bangalis were virtually excluded.

History bears witness to the fact that the denial of political power and also the demand for provincial autonomy was compounded by the assault on the cultural identity of the Bangalis, with the proclamation of Urdu as the only national language of Pakistan. Here also Bangabandhu was closely involved with the protest emanating from the student and the cultural front. Additionally, one could see that the political domination and cultural subordination of the Bangalis was further compounded by the denial of democratic access to the economic opportunity being created by the Pakistan State.

Professor Rehman Sobhan comments that, "This denial of political right and economic opportunity to the Bangalis of Bangladesh provided the dynamic of the demand for democracy and self-rule for Bangladesh which constituted the central motivating force of Pakistan's politics for twenty four years of its existence as a unified State". Bangabandhu realised quite early that the ruling cabal was bent on establishing a Pakistani identity over a Bangali identity and that this coterie mischievously revived the notion of religious identity. To the Pakistani establishment, the assertion of a Bangali identity was un-Islamic as well as anti-Pakistani.

The highlighting of the separate political and economic aspirations of the Bangalis in Pakistan and their distinct cultural identity was no easy task. Major political struggle of the Bangalis, starting from the Language Movement of 1952 to the mass upsurge for democracy in 1969 were driven by the passionately held notion of separateness. For this separateness to grow into a sense of shared nationhood, it required a major political effort. The political stewardship for such venture was surely Bangabandhu's, who performed the catalytic act of political entrepreneurship needed to forge a sense of nationhood for the Bangalis.

It is also a fact of history that Bangabandhu played the politically critical role of institutionalising the growing sense of separateness between East and West Pakistan by presenting his historic Six Point Programme before the people of Pakistan in 1966. This programme brought into sharp focus the urgency of devolution of political power, policymaking and administrative authority as well as command over economic resources to the provinces. The Six Point demonstrated, for the first time, a formal recognition that political coexistence between East and West Pakistan, even within a democratic central government was no longer feasible.

Students of political science and history, in particular, need to understand that Bangabandhu realised the imperative of an overwhelming mandate from Bangalis to generate enough pressure on the military junta of Pakistan to devolve power to the Bangalis as per the Six Point Programme. He also believed that rejection of the universal demand of the Bangalis would jeopardise the very foundation of the Pakistan State. As events unfolded later, this assumption of Bangabandhu turned out to be prophetic.

Bangabandhu was extraordinarily brave and sagacious enough to seek a comprehensive popular mandate for his Six Point over the heads of his Bangali political rivals. This was necessary because in the preceding years all attempt to resist external political domination by Pakistani elite failed due to divisions amongst Bangali political leaders. Therefore, Bangabandhu's political campaign from March 1969 emphasised on the separateness of our social, political and economic life. He successfully exhorted his Bangali audience to vote together to proclaim the right to live a separate life from West Pakistan.

To carry the message of Bangali nationalism into the consciousness of every household of Bangladesh, both rural and urban, was a huge task. Here also we witness the outstanding organisational skill of Bangabandhu. The most striking poster of the time titled "Purbo Bangla shoshan keno?" (Why Eastern Bengal is oppressed?) presented in simple language the statistics of disparity between East and West Pakistan. For the message to land on the doorstep of the voters, required large-scale party organisation and dedicated work. Bangabandhu's enviable organisational acumen facilitated the accomplishment of the monumental task.

In 1970, the massive electoral victory achieved due to Bangabandhu made complete regional autonomy a non-negotiable demand of the Bangalis. In early 1971, a resurgent Bangali people and a buoyant Bangabandhu convinced the obstinate military and scheming politicians that there was no scope to compromise on Six Point demand through inducement of power sharing at the centre. By this time, for Bangalis, the Six Point had turned into the only constitutional solution to the political crisis in Pakistan. The new found sense of nationalism had already started inspiring the demand for full political independence.

The uniqueness of Bangabandhu's leadership lay in the fact that national sovereignty was inculcated into the consciousness of the Bangali masses through a deliberate political process. Years of political mobilisation by Bangabandhu made the Bangalis conscious of their identity. The mass character of consciousness provided the underlying strength to the nationalist movement and the assertion of national sovereignty.

Bangabandhu's cruel assassination was an abominable conspiracy to marginalise the historic consciousness of the Bangalis. His assassination, quite clearly, was an assault on the inspirational sources of our nationhood. At present, when the nation mourns Bangabandhu's demise, it is time to gratefully remember and salute the great son of Bengal and at the same time renew our pledge to make sustained efforts to preserve our distinctive national identity.

Muhammad Nurul Huda is a former IGP.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments