When students have to do the job of the law enforcers

Two days after the deaths of two students and mass student protests all over the city, the prime minister directed the police to act against those responsible, and the High Court directed the government to form an independent inquiry committee to conduct a survey on the fitness of public motor vehicles in service. In this time, the students did what the law enforcers should have been doing all along—stop and check if the drivers of buses, cars, trucks and motorbikes on the road had valid licences. They stopped CNGs to see if they were running on meters. In short, they showed how traffic laws should be enforced, something that the law enforcers have ignored to do so far.

Meanwhile, these young boys and girls have been making way for ambulances—and probably, because of this important intervention, patients were reaching hospitals faster than they usually do. What is more embarrassing for our authorities is that members of the police and even high-level officials were seen flouting the rules—these amazing boys and girls had the courage to stand up to them and demand that the law is enforced equally for everyone.

And the absurdity of it does not end here. On Tuesday, a video clip that went viral on social media showed law enforcers in a laguna, driven by an underaged driver, which had crashed into another car on the road. To top it all off, the police were seen defending the underaged driver in the face of the public questioning them why they were in a vehicle driven by a child in the first place. No wonder college kids took to the street. If they didn't, the two deaths which sparked this off would be forgotten soon enough, and the bus drivers, bus owners, and the powerful who back them would continue to reap profits through the lawlessness that rules our roads. Of course, the police initially wasted no time to beat up some of these students, who they deemed to be a bigger threat than the speeding buses crashing into pedestrians.

Law, where art thou?

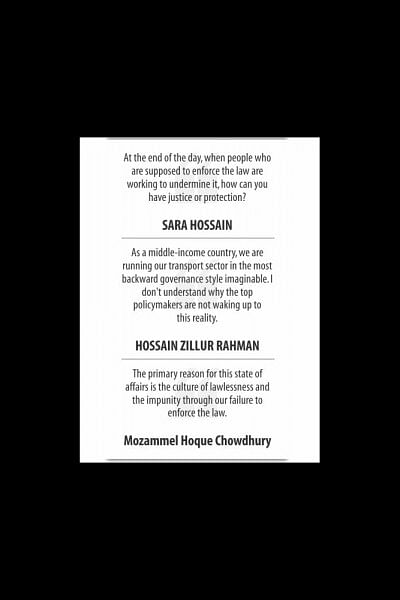

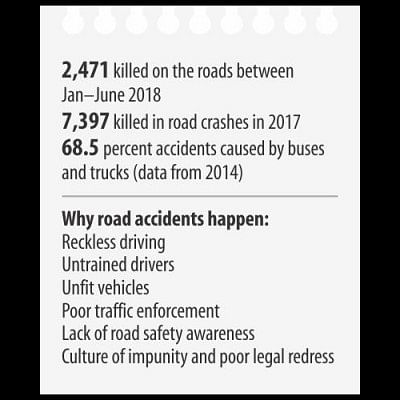

According to Mozammel Hoque Chowdhury, secretary general of Bangladesh Passengers' Welfare Association (BPWA), the primary causes of this state of affairs are two: complete disregard for the law and the failure to punish the law-breakers. He says: "In most cases of road accidents, people do not want to file cases, since they feel that nothing will be done. In incidents where cases are filed, the perpetrators mostly walk away free." Data from the BPWA show that more than 7,000 lost their lives in 2017 in road crashes. Just in the first six months of this year, at least 2,471 people were killed on the roads, according to the National Committee to Protect Shipping, Roads and Railways. Yet, everything that is wrong with the public transport sector, from hiring unskilled drivers, sometimes underaged, to allowing the operators to do whatever they want on the roads with the police turning a blind eye, continues.

In 2011, after 44 students were killed when a pick-up truck veered off the road and plunged into a ditch in Mirsarai, Chittagong, the Bangladesh Legal Aid Services Trust (BLAST) filed RTI applications to two ministries. According to the information provided by the Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges, in the ten years from 2001 to 2011, there were 41,791 incidents of road accidents according to police reports. Data from the Home Ministry, on the other hand, had records of 36,439 incidents, in which 27,595 people lost their lives in the same period. But in these thousands of incidents, just about 2,269 people were convicted, and only 257 of the perpetrators sent to jail. In the 36,199 cases that were filed, charge-sheets were submitted by the police (after an investigation) in only 19,186, and final reports were submitted for 16,261 cases. Predictably enough, no information was provided by either ministry about compensation for the victims and their families.

That the protesting students on the roads have been checking the licence and registration of buses, trucks and other motor vehicles also goes to show the extent of the irregularities in the operation of these vehicles—it is common knowledge that buses without route permits and proper fitness are driven by inexperienced drivers with no licences. But even when it comes to the drivers who do have licences, irregularities in the process of obtaining them mean that a licence is no guarantee of the skills required. A 2014 study conducted by Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) titled, "Road Safety in Bangladesh-Ground Realities and Action Imperatives", which interviewed bus and truck drivers, found that 20 percent of drivers admitted to getting licences without giving the required test. This is by the drivers' own admissions—the actual numbers are likely to be much higher. The same study also found that 81 percent of the drivers surveyed learnt to drive without any formal training process. Of the drivers who were involved in accidents, 42.3 percent faced no subsequent penalty at all. Only 34.6 percent had to pay fines; drivers faced court cases in only 10 percent of incidents. And in only 1.3 percent of cases, the licence of the driver behind an accident was actually impounded. Compare that with the fact that 68.5 percent of accidents on the roads are caused by buses or trucks.

Sara Hossain, a Supreme Court lawyer, says examples of investigation and prosecution after such road accidents are rare, and gaps in terms of accountability continue to perpetuate reckless driving on the roads. Clear provisions of the law, which if enforced would go a long way to curb reckless driving, are not implemented properly.

"Almost nothing is done in terms of preventive action. There have been a few good steps, like the identification of blind spots on highways and putting signs near them after the deaths of director Tareque Masud and his colleagues. But take speed limits for example. Very few roads and highways in our country have speed limits, although our law states that they should be there. So, everyone in effect drives as they want since there is not attempt to control speed and no initiatives taken to hold people accountable for driving at reckless speeds or causing injuries," she says.

She points out that the very fact that courts have to step in time and again to direct the government to act is a sign of the executive authorities not giving road safety a priority through implementing the laws. "Even when compensation awards are made, they are often not enforced. There are major gaps in the system, with assessing and paying compensation, and with the role of insurance companies. In most countries, if such accidents happen, compensation claims are made, and the insurer has to pay, recovering from the insured party. No vehicle is allowed on the roads without being insured. But we don't see this practice in our country," she adds.

Compensation awards are difficult to enforce because those who are held responsible in the courts are seldom held accountable afterwards and rather enjoy a certain level of impunity and political protection. So, in effect, not only are preventive actions such as ensuring that only skilled drivers are driving road-safe vehicles following traffic rules not taken, but the scope for people to seek remedial measures following an accident is also limited.

Safety not a concern

A new draft law for road transport has been under consideration of the cabinet for some years now. Only now, on Wednesday, our Road Transport and Bridges Minister finally stated that the act will be placed in the coming week's cabinet meeting. Speaking of this, Hossain Zillur Rahman, Executive Chairman at PPRC and convener of the civic platform Srota (Safe Roads and Transport Alliance), says: "A big gap in this is the objective of the law—why is the law being made? It is called the Road Transport Act. One of our primary recommendations was to include the issue of safety in the title and preamble of the law to transmit the message that this law is being made for the safety of the people. The issue of safety has been completely disregarded in the new law. The lack of a preamble stating the objective of the law shows that road safety has not been prioritised."

He also points out that there are gaps in both the current and the draft law regarding the remedial measures after accidents. The law sets no specific procedure for investigation after accidents, and currently such investigations are conducted by the police as criminal cases. But accident investigation requires specialised expertise. "Even in India, accident investigations are mandated by the law. This is a big gap in our Motor Vehicle Ordinance and the new draft law."

The issue of compensation is not clear in the new law either—no specific compensation assessment procedure and how victims can seek compensation is clearly stated.

A case of conflict of interest

However, non-implementation of the existing laws and the gaps in our laws are just one part of the reason why anarchy rules the roads and the number of road casualties is so high. Ultimately, the core of the problem is whose welfare is being prioritised. Why have law enforcers so far been unwilling to check if drivers on the roads have valid licences? How are licences issued without ensuring proper tests? And why is there no specific mechanism and procedure for compensation for victims?

Comments made by certain public representatives hint at the issue that everyone has known for a very long time. Sara Hossain cites the example of the Tareque Masud case. When a key witness in that case was deposed in court, the truck workers' association went on strike apparently with the backing of a high level official stating that they would oppose any decision taken by the court. "The workers were resorting to extra-legal means with powerful political patronage to try to deny the victims the chance to even ask for justice.

"There is a conflict of interest in this. A member of parliament has a responsibility to ensure that laws are being made and enforced to safeguard citizens' rights. They cannot be acting as spokespeople for vested interests. We have, unfortunately, a situation where we have 'representatives of the people' who are really representing the bus operators and drivers," she says.

Hossain Zillur Rahman sees the root of the problem as one of political governance, where mis-governance has created a "legally sanctioned anarchy" in road transportation. Referring to the BRTA law which has already been passed, he says, "There is a provision in this law for a committee—the RTC (Road Transport Committee)—which determines route permits for buses and how many buses can operate in a particular route. Unfortunately, the BRTA has no control over this body, and it is virtually under political control. Political mis-governance leading to a culture of impunity—that is the heart of the problem."

Frustration and a hope for reform

It should be clear by now that the anarchy in the road transport sector is not a simple issue of bad driving, but one that has been created because powerful people have prioritised the profits and interests of the owners over passengers' welfare. That so many students from many educational institutions across the city took to the streets in the last few days is a sign that they have had enough. "At the end of the day, when people who are supposed to enforce the law are working to undermine it, how can you have justice or protection?" as Sara Hossain aptly puts it. Hossain Zillur Rahman echoes the same thought: "Why are the students out in the streets? Because there are not proper remedial steps, and the culprits often escape justice."

Hopefully, the mass agitation will bring change. Hopefully, our leaders will feel the irony of the situation in which students have to take to the streets to ensure drivers have valid licences while law enforcers are seen going around vehicles driven by kids. The passing of the new draft law, after making changes to it to reflect the safety and welfare of citizens, could be a starting point. Ensuring what our law already entails, such as speed limits, could go a long way too. Urgent reforms in the way the RTC and the BRTA act are crucial. The late mayor Annisul Huq's initiative to reduce the number of bus operators in the city from over 190 to five, in a bid to overhaul the public transport sector and get rid of the syndicates that virtually control it, was a promising start. "Our late mayor had initiated some much-needed reforms for this, but after his death, all these have been put under the blanket—this reform was crucial," says Hossain Zillur Rahman.

"As a middle-income country, we are running our transport sector in the most backward governance style imaginable. I don't understand why the top policymakers are not waking up to this reality." Can the children who have taken to the streets calling for reforms finally wake them up?

Moyukh Mahtab is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments