How can Dhaka become more resilient to future pandemics?

Cities have generally been the epicentres of the devastation caused by Covid-19, fuelling debates around the world on how to make cities more resilient against future pandemics. A range of questions are being asked—What can we learn from the ways cities responded to past pandemics? How do we achieve quality public health through city design? How would the nature of public squares be complicated by the needs of "social distancing"? How do we minimise the risks of such disease hotspots at high-density public transportation, markets, workplaces, schools and entertainment venues? How do we reimagine the relationship between cities and nature as a way to make cities greener and healthier? How can we leverage urban data to provide efficient and equitable public health services? What kind of urban lifestyles can city design foster that would reduce pre-existing health conditions of vulnerable people? And how can we employ urban design to mitigate economic, social and racial injustices that the coronavirus crisis has both revealed and augmented?

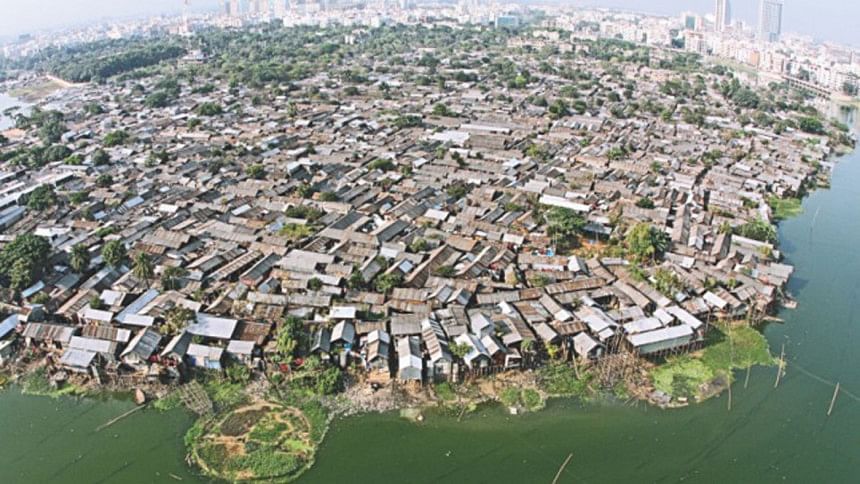

There is, of course, no universal formula for a city's pandemic preparedness. Cities vary in terms of their population density, culture, economy, public health, governance and resources. Dhaka's preparation strategies may not be the same as those for New York City. For example, social distancing can present a very different set of urban meanings and public receptions in different cities. How would you socially distance yourself if the space isn't there in the first place? In a poverty-stricken, ultra-congested slum, social distancing could be a cruel joke. If the footpath is four feet wide, how do two people stand six feet apart, as recommended by public health officials?

Yet, there are shared experiences that could be instructive for cities across regions, economic geographies and cultures. For instance, learning from history matters for all. Crises inspired creative solutions in the past. In the mid-19th century, the urban impacts of the Industrial Revolution were revealed by the shockingly unsanitary living conditions of the working class poor who came to cities to work in the factories. Infectious diseases, particularly cholera, were rampant. One author wrote in 1883 about the human horrors inside the workers housing in London: "Every room in these rotten and reeking tenements houses a family, often two. In one cellar a sanitary inspector reports finding a father, mother, three children, and four pigs!" In his novel Oliver Twist (1837-38), "the spokesman of the poor" Charles Dickens hauntingly portrayed the dark underworld of London.

In response to deplorable urban conditions, the cities of London, Paris and New York sought housing reform and modernised their sewage infrastructures to contain cholera epidemics. These metropolises gradually devised new urban zoning laws to prevent unhygienic overcrowding that frequently led to disease outbreak. Thus, the modern era of urban sanitation began. At the height of anti-British agitation in India, Gandhi proclaimed: "Sanitation is more important than political independence."

The birth of urban planning was tied to the growing awareness of sanitation as the foundation of public health around the turn of the 20th century. The discipline emerged as a result of the overlapping works of three groups of people: architects, public health professionals and social workers. Architects were concerned with improving and reorganising the physical conditions of the city. Public health professionals focused on the city's poor infrastructure—water supply, sewage collection or waste disposal—as a way to prevent epidemics. And, social workers sought to improve the lives of the urban poor by promoting housing reform and reducing their gruelling work hours. The efforts of these groups ushered in the idea of comprehensive urban planning, powered by a universal sense of moral economy.

That was over a hundred years ago. Today, we have become accustomed to the concept that each city has its own political economy, social and cultural character, and anthropological challenges. It is in this context we need to reimagine post-Covid-19 cities in Bangladesh.

Most importantly, we should see city design as a public health initiative, wherein "public health" implies a fusion of physical and mental wellbeing, aesthetic and cultural fulfilment, the ability to live life without fear, and social conditions in which all people have equal access to opportunities. When public health is understood as a collective social contract, hospitals, urban trees, playfields, footpaths, clean rivers and kacha bazars can all be considered public health amenities.

Speaking of kacha bazars, we all know how important they are in our cities as "informal" marketplaces that serve as community junctions where local people buy fish, meat, spices or vegetables at affordable prices. The alleged origin of Covid-19 in a Chinese kacha bazar or wet market in Wuhan has provoked questions as to how safe it is to allow this type of informal, and almost always unsanitary, marketplace inside dense urban neighbourhoods.

But think about it. Who wouldn't enjoy going to the kacha bazar in Mohammadpur or New Market in Dhaka and experience their poetic insanity, their intoxicating hustle and bustle? Even though they don't trade exotic animals like their Chinese counterparts, wet markets in Bangladeshi cities warrant a new scrutiny from a public health perspective. With the health hazards of exposed meat and drying blood, severed cow heads kept next to vegetable stalls, and fish stored in polluted water, the traditional kacha bazar could easily become a pandemic tinderbox.

Should they be removed from congested urban areas or should they be redesigned to meet public hygiene standards? Like the rickshaw debate (whether they should be taken off city streets or not), kacha bazars can present a policy dilemma. On the one hand, the livelihoods of local traders and community values are at stake and, on the other, there are public health risks.

The wet markets are not a problem of developing countries alone. There are over 80 wet markets in New York City. A nonprofit group called Slaughter Free NYC is working to have them banned on the grounds that they pose serious public health risks. We need to start reimagining wet markets in the midst of our cities. Similarly, the placement of public toilets in busy urban intersections should be examined closely. As much as they serve the public interest, they could also be air- and water-borne virus factories. Is the unsanitary public toilet a design problem or a behavioural problem? Would toilet hygiene in our country require a cultural revolution? In 1925, Gandhi wrote: "… a lavatory must be as clean as a drawing-room." It was a pointed critique of South Asia's toilet hygiene.

Another issue that comes up frequently in debates on post-pandemic urbanism is crowding in public transportation. What can Dhaka, Chattogram, Khulna, Sylhet or Rajshahi do about it? Our buses, tempos and trains are jam-packed. Social distancing is both a luxury and an impossibility. Should facial masks be made legally mandatory in mass transit? Alternatively, should we promote personal mobility by means of biking and walking? European cities are aggressively championing biking as a triple-win proposition. Biking is healthy; it reduces crowding in mass transportation; and it doesn't discharge any carbon into the city air. But how safe are our already packed streets for biking? Maybe in Barishal, but not in Dhaka. What will it take for us to reimagine Dhaka as a South Asian Amsterdam?

Walking in our cities has never been a pleasurable or efficient urban activity. Footpaths often either don't exist or are occupied by informal markets. Furthermore, an entrenched bourgeois class element makes walking in city streets a socially incriminating subject. Creating a true pedestrian culture would require no less a behavioural revolution. Urban administrators, planners, architects, healthcare professionals and social workers should come together to re-conceptualise the footpath as a public health infrastructure that can help reduce obesity, resist diabetes, and encourage people to better experience their city. Being healthy means not having preexisting health conditions, thereby reducing people's vulnerabilities during the pandemic. Should footpaths be covered or arcaded, so that people can use them in all seasons, during the monsoon and scorching summer?

Pandemic preparedness would require a careful consideration of the city's economic geography and how it might perpetuate discriminatory public health policies. It is typically the urban poor, ghettoised in their impoverished, unhygienic and overcrowded squatter colonies, who bear the brunt of a pandemic. Covid-19 killed people in the Bronx, the poorest of New York City's five boroughs, at a much higher rate than other boroughs. Grinding poverty, lack of quality hospitals, racial discrimination and social alienation made the Bronx more vulnerable than any other borough. Bangladesh can learn from the Bronx experience.

Urban resilience needs meaningful investment in public health infrastructures, including affordable hospitals. In the 2020-21 budget, Bangladesh's expenditure on health is a little over one percent of GDP (India's is similar to Bangladesh; Norway's is over 10 percent, one of the highest in the world). The truth is that our development vision prioritises flyovers but not public hospitals. As the coronavirus crisis rages in Bangladesh, hospitals, more specifically oxygen, have literally become the fault line that separates the haves and have-nots. Eliminating this fault line would require envisioning a new moral economy as the bedrock of development.

Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian and urbanist. He teaches in Washington, DC, and serves as Executive Director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at BRAC University. He can be reached at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments