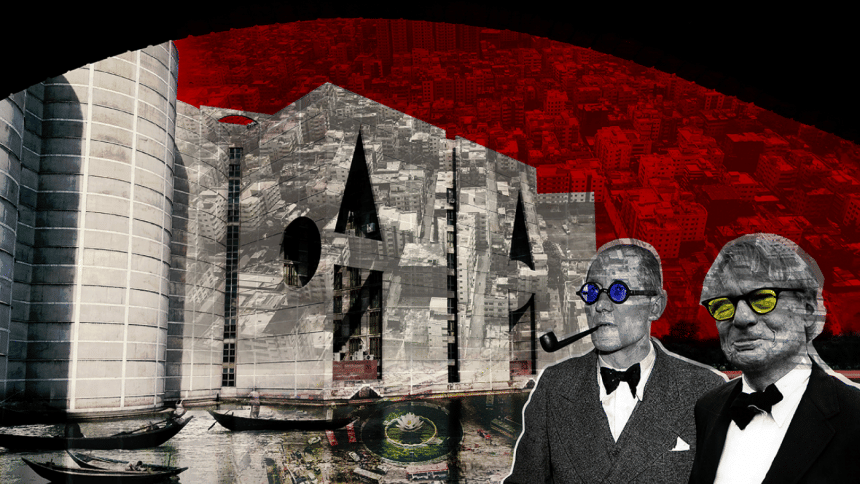

Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn visit Dhaka

At a public place in the afterlife, Louis Kahn ran into Le Corbusier. The Franco-Swiss architect was pleased to see the esoteric architect/guru from Philadelphia. They sat on a Henry Moore bench, custom-built for eternal life, under a leafy tree. As one would imagine, it was not easy for two heavyweights to strike up a conversation.

After an uneasy pause Le Corbusier asked, "So, I hear you designed the large parliament complex in Dhaka which was first offered to me?"

Looking away at a heavenly bird that chirped on a nearby tree, Kahn replied, "Yes. In 1965, when you perished during your Mediterranean swim in the south of France, I was actually in Dhaka. We worked feverishly to get the design work for the parliament done before agitation for independence in the then East Pakistan would take it all away. Politically, it was a tempestuous time there. Bengalis were very unhappy that West Pakistan's ruling elite was depriving them both politically and economically. The streets in Dhaka were rough. But I kept my cool and went on with the work. So, why did you not accept the Dhaka project?"

"Well, I was too tired after Chandigarh. During the 1950s, the Indian bureaucracy kind of drained me. I just couldn't take on a grand new commission in the Subcontinent! By the way, did you visit Chandigarh?"

"Yes, of course, I was already in India, designing the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) in Ahmedabad. My first trip to India was in 1962 and your new capital in Punjab was being described as India's new, modern face. I visited Chandigarh with great interest. I knew you had struggled there to make something that needed to be timeless and to shoulder India's burden of showcasing its own modernity."

"You can say that! Chandigarh was sort of my existential crisis. I have been writing about cities since the 1920s but I needed a project with which, and a leader with whom, to realise my dreams of the Ville Contemporaine and the Ville Radieuse. With Chandigarh and Nehru came my happy opportunity. But tell me about Dhaka. How was the city in the 1960s when you got there and what kind of problems did you face?"

"Well, Dhaka was then a quiet city with a rural ambiance. Very few cars and lots of green! The 200-acre site that was given to us at the beginning was on the northern border of the city. The area was mostly a vast paddy field. The capital of East Pakistan was not really a city then. It was more like a large village with minimal urban infrastructure and some buildings. On my arrival in Dhaka, I took a boat ride down the Buriganga River, saw some interesting canals and wetlands, and tried to understand the role of water in this vast delta. I also visited some Mughal buildings in Old Dhaka. Gradually I began to think of what a parliament complex should be in a context in which there wasn't much urban history."

"I know you departed from that world below in 1974. Interestingly, from a men's room at the Pennsylvania Station in New York, on your way back from the Indian Subcontinent. You lay unclaimed for a few days because your passport didn't show an address, right? I too had a dramatic departure from the world. My body floated in the Mediterranean and was found by bathers. Don't you agree that both our ends were rather strangely poetic? By the way, who finished the project after you left?"

"I died broke, but I was fortunate to have a few very trusted architects in my team. They took the completion of the project almost like a religious duty. The parliament complex at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar was eventually completed in 1983, nine years after I took off. The 11-storey concrete building survived the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. In fact, the West Pakistani pilots who were bombing East Pakistan thought it was a vast ancient ruin. So, they didn't bomb it! In the end, I think it turned out to be a neat project. Architects loved it, people loved it, the administration loved it. It seemed to have symbolised the independence struggle of Bangladesh."

Corbusier didn't seem too eager to believe Kahn. He said with hesitation, "But I also heard that some thought it was too much like a castle—a fort—too removed from the ordinary life of the city; and, too expensive for a war-ravaged country!"

"Well, I was interested in a monumental public institution and an architectural language for it that would inspire a new nation. In my design for the parliament complex of Bangladesh, I wanted to be Roman, Mughal, Bengali, and deltaic, all at the same time. In the end though, I wanted none of these. I strove for an archetypal building onto which people could project their dreams and hopes."

"That's what all architects wish for, don't they? I had tried to achieve that in Chandigarh. In any case, how's Dhaka these days? Have you been following things there?"

Kahn seemed excited suddenly, "Why don't we take a quick trip to Dhaka without anybody noticing us? I am sure we can manage the heavenly guards up here."

Corbusier sounded energised too, "Yes, let's do it. I wish I had visited the city when I was doing Chandigarh." There was a massive explosion, followed by lightning and Corbusier and Kahn appeared at Motijheel, about 200 feet away from Shapla Chattar. The time was 11:45 in the morning. It was hot and humid. The streets were crowed and cacophonous.

Corbusier seemed shocked to see the intensity of traffic congestion in downtown Dhaka. "When I was proposing city concepts back in the 1920s and 1930s, I thought that cars were the answer to the cities of tomorrow; that cars would give people mobility. So, cities like Chandigarh and Brasilia were inspired by the need for motorised vehicles. But Dhaka feels like a place from another planet! I thought the country was poor. How on earth are there so many cars?"

"Well, that's the paradox. Instead of learning from our failed experiences, the developing countries are making the same mistakes we did in Paris, New York, and London. We thought that we must have cars to go around the city. In America, except for a few main cities we never really had public transportation systems that served all economic classes. So, people bought cars for mobility and for prestige. Sadly, Dhaka is repeating that urban ritual. With the amount of fuel that is burning, in this Dhaka air we may die again, today! The city that I knew during the 1960s was pleasant, even though it was very hot and humid during the summer. I walked a lot around Farmgate and Agargaon to get a sense of the site for the parliament. The Bengali architect Muzharul Islam was my guide. He was energetic and eager to introduce me to Bengali culture. There were very few cars in the streets and you could walk safely."

Kahn continued, "People were more interested in talking about politics and West Pakistani conspiracies than cars and other stuff. Anyway, let's get out of here. The honking is driving me crazy! Did you try the rickshaws in India?"

"Yes, a few times, in Ahmedabad. An Indian architect named Doshi, who was my good friend, took me around to see the old city in Ahmedabad. You probably know Doshi too."

"Of course, Doshi was my guide when I was there working on IIM."

The two gentlemen hailed a rickshaw. Kahn directed the rickshawalla to Manik Mia Avenue. The two men enjoyed the ride, as they discussed city planning, road congestion, over population, urban politics, and, of course, building, building everywhere. They both wished for a chance to fix the city. Corbusier insisted that the capital must be moved somewhere else in Bangladesh in order to alleviate the pressure on Dhaka. But this was classic Le Corbusier: Taking the capital somewhere else would mean he would be the logical choice to design the new capital! Kahn was reluctant to abandon the existing city. He suggested decentralising it and argued that nothing would solve Dhaka's problems unless people were able to find opportunities elsewhere as well.

When they arrived at Manik Mia Avenue, Corbusier alighted from the rickshaw and stepped on to the broad sidewalk. He gazed toward the parliament building for a long time.

In a measured tone he said, "It doesn't look democratic, but its allusion to ancient grandeur is intriguing. I think your building is catastrophically modern. It moves us with both a timeless spirit and melancholy. It gives the haunting, sublime experience that every edifice ultimately aspires to achieve. Still, I think you could have done more. You had the chance to do a master plan for the city, instead of just a parliament complex. An architect should never create just the project that was commissioned to him. He must improve the very location for which the construction is proposed. Here, you have created a false Taj Mahal, surrounded by a sea of urban absurdities. Where is the good society?"

"A small spatial ritual, a tiny order, a quiet institution, a meditative monument can be the beginning of a good society, of a resilient nation. That is this, here. That is what I dreamed of in the 1960s."

For the rest of the time that the two men spent there, Corbusier was silent until he pronounced, "Great architecture ultimately gives us a spiritual experience, one in which the temptation of heaven and the fear of hell become less important. A spiritual reckoning is essential for social transformation."

"Dhaka needs it," Kahn responded. "Without that feeling, it is impossible to abandon a life of false luxury and empty promises. Shall we return to the skies?"

Corbusier replied, "Yes, let's. I think our journey has either ended, or just begun."

Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, urbanist, and professor. Email: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments