The sociology of eco-grief: Saving Suhrawardy Udyan

Eight years ago, in May, a large crowd staged a sit-in at Gezi Park, next to Taksim Square, Istanbul's bustling public plaza in the downtown of its European side. People wanted to save the park's 600 trees that would soon be cut to clear space for a massive "Ottoman-style" shopping mall. What started as a local environmental movement quickly snowballed into a national agitation against heavy-handed government tactics.

The Gezi Park demonstration also revealed something fundamental and even universal: people's ecopsychology—the emotional connection between humans and nature. When that connection is severed, humans feel pain. A growing body of research indicates that contact with natural environments contributes to improved health and psychological wellbeing. This is particularly evident in dense urban areas.

Trees are the most common signifier of nature. They are our most intimate connection to nature. Khalil Gibran wrote: "Trees are poems that the earth writes upon the sky." When we see a familiar tree in our neighbourhood or park felled, we experience anguish. The Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht calls this melancholic feeling "solastalgia"—a kind of eco-grief experienced by a community when it feels that its environmental umbilical cord has been broken.

Almost a hundred years ago, in 1928, Rabindranath Tagore poignantly foreshadowed the solastalgic crisis in our cities with what could be called a "Bolai effect." Tagore's character Bolai is an introvert, a motherless, nature-loving boy who had the habit of staring at trees for hours and speaking with them without uttering a word. He would flinch at the mere thought of cutting a tree. In a debdaru forest, Bolai would feel at home and silently communicate with large trees, as if they were people—his uncles, his grandparents, his friends. The Bolai story reveals Tagore's deep commitment to a spiritual dimension of environmental ethics. In a deltaic country with a fragile ecology, we are all supposed to be Bolais.

The environmental disaster at Suhrawardy Udyan has inspired a broad Bolai effect. It is heartening that people are protesting this "ecocide." But it is also tragic to see that on the 50th anniversary of Bangladesh's independence, the Ministry of Liberation War Affairs and the Ministry of Housing and Public Works are spearheading a misguided development project at Suhrawardy Udyan that would desacralise the glorious histories of the Liberation War. Why fell trees that are integral to the city's cultural ecology? Who needs any restaurants inside a historic park? Would any civilised society today construct a mammoth parking lot inside an iconic park?

There is no restaurant inside Washington DC's National Mall—the two-mile-long expanse of open space that serves as a symbol of democracy at the heart of the US capital. Dhaka has no shortage of restaurants, and Suhrawardy Udyan is the last place to need another seven restaurants. We do not have to commercialise every square inch of Dhaka and other cities. There are certain areas that should be protected like sacred ground, without the profanity of eating and partying. The whole point of going to Suhrawardy Udyan should be to understand historical legacies, learn the names of trees, hear birdsongs, experience solitude, heal the mind, breathe fresh air, and meditate, not eat burgers and arrange loud picnic parties! A park is where people learn to develop an empathy for and an understanding of the biology of how nature nurtures us. Any development project for Suhrawardy Udyan should include a mission to educate the public about the histories of 1971, as well as horticulture.

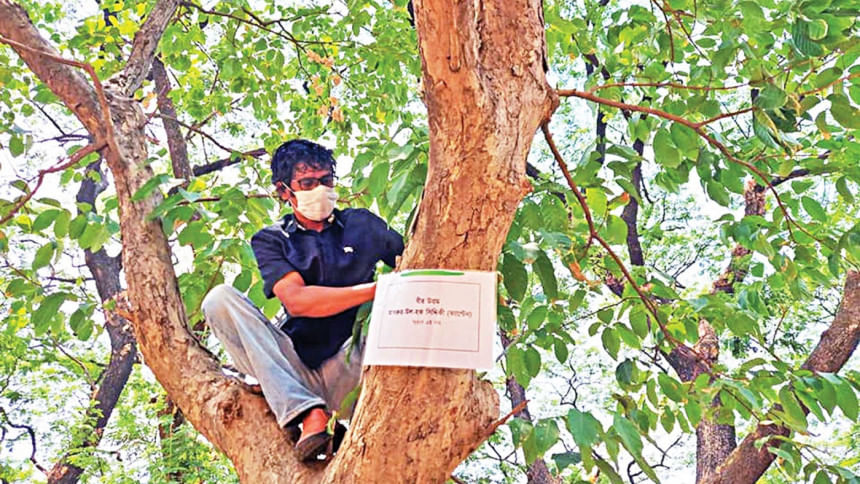

A writ petition has been filed at the High Court to challenge the felling of historic trees at Suhrawardy Udyan, and the clearing of trees has been halted in the meantime. The other day, a little girl came to the park with her mother to protest. Her placard read: "Give me oxygen. I want to live." Ironically, the slogan is eerily similar to that of Covid-19 patients across hospitals. Perhaps the little girl reminds us that trees are humanity's best defence against pandemics. I do not think I have seen a more brilliant idea of activism than this: To save the remaining trees at Suhrawardy Udyan, environmental activists have named them after different muktijoddhas (freedom fighters). This is their symbolic resistance: to cut trees is to kill freedom fighters. Deeply moving.

But is this romantic environmentalism enough to stop the kind of ill-conceived development that is mutating the ecological and historic DNA of Suhrawardy Udyan? While we need activism to build public awareness of environmental responsibility, it is no longer effective as a deterrent, primarily because it is mostly reactive and resistive. It does not anticipate potential environmental disasters and help create preemptive policies to prevent them from happening in the first place. Furthermore, current activism neither offers acceptable alternatives to bad development, nor build broad political coalition that could countervail the malpractice of top-down planning. It is time to reengineer the very idea of activism against environmental injustice.

Development is not the problem. On the contrary. Development is necessary. But land-grabbing, crony capitalism, nefarious arrangements of bhag-batoara, and political opportunism in the name of development are the problem. Stifling the public interest to maximise personal gain is the problem.

What environmental activists need now are new types of coalition building and strategic advocacy. A coalition of like-minded politicians, administrators, bureaucrats, professionals, academics, civil society, and activists would make it impossible for an imprudent minister or a chairman to make unilateral decisions to transform a national park or a heritage site. Evidence- and knowledge-based strategic advocacy should focus on building public consensus that environment-friendly development is the greater good in the long run. Strategic advocacy should empower responsible and empathetic leaders by encouraging them to commit to an ethical vision of environmental stewardship rather than exclusively relying on legislative measures. Strategic advocacy should help institute policymaking that warrants accountability in public works.

Nobody reminds me of better strategic advocacy than Rachel Carson, the acclaimed author of Silent Spring (1963), a book that galvanised the environmental movement in the USA in the 1960s. In Bangladesh, it is Dwijen Sharma, the eminent botanist whose study of nature struck a chord with the public.

Suhrawardy Udyan is too important a historical venue to be the playground of a ministry or two. That an architect of the Public Works Department can singlehandedly redesign Suhrawardy Udyan without any national oversight and expert vetting is absurd and infuriating. A park redevelopment that requires the felling of existing trees that are intertwined with histories of Bangabandhu should be rejected. Any development of this hallowed ground where many landmark political events—from Bangabandhu's March 7 speech to the surrender of the Pakistani army on December 16, 1971—took place must be scrutinised by a high-powered commission comprising public officials, politicians, experts, and members of civil society. The Commission of Fine Arts, a federal agency in Washington, DC, is "charged with giving expert advice to the President, the Congress and the federal and District of Columbia governments on matters of design and aesthetics, as they affect the federal interest and preserve the dignity of the nation's capital."

The idea of historic preservation should not include just TSC, Kamalapur Railway station, Ruplal House, and Kantaji Mondir. It should also include trees, waterbodies, and biodiversity that bear witness to national narratives. The development that comes at huge environmental cost is no development at all. The consensus that in a socially mature society, it is not okay to replace trees with restaurants, must become a vigorous political force.

According to some news media, at least 150 trees have been chopped down in Suhrawardy Udyan. Is it time we discovered the Bolai in each of us? We should all go to Suhrawardy Udyan and hug the trees that remain. I do not know how to process my own hypocrisy that I am preaching biophilia from the other side of the planet. In moments of self-doubt, I draw strength from the belief that trees not only provide us with abundant oxygen, but also forgive, like mothers. Or Mother Nature?

Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, urbanist, and educator. He teaches in Washington, DC, and serves as Executive Director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism (Ci+AU) at BRAC University. [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments