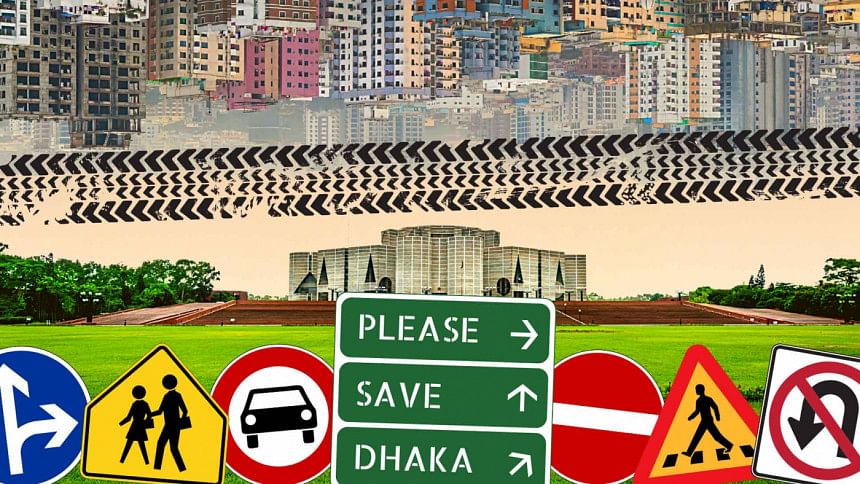

There is just one way to save Dhaka

The notoriety of Dhaka's traffic is now daily news. Civil society members have been venting frustration about this maddening crisis. Transportation engineers—local and international—have been busy offering solutions akin to those in highly developed cities like Melbourne or Singapore. These solutions include, among others, improved public transportation and automated ticketing systems, dedicated lanes for bus rapid transit, smart road signals, and coordinated traffic management. They are all well-meaning suggestions. But they are, alas, pipe dreams, given our tangled urban realities. While technically sound, these solutions are likely to fail, because they ignore complex sociocultural issues and public behavioural patterns that make traffic congestion an insurmountable knot in the first place.

The hard reality is that Dhaka's traffic problem will not go away anytime soon. The causes for the city's clotted streets can't be undone overnight. Technical solutions alone are not enough, since the capital city's traffic jam is the result of a complex combination of sociocultural factors, lack of rational land use, and misguided urban governance. Let me explain these three issues briefly before contemplating ways forward.

First, to unpack the sociocultural roots of our capital city's notorious traffic congestion, it would be logical to zoom in on its primary contributor: the private car. Private cars occupy 70-80 percent of Dhaka arteries, while serving only 5-10 percent of daily commuters. This is a glaring example of social injustice and inequity. Neither Copenhagen nor Singapore would ever allow this asymmetric distribution of urban resources. Let's put it in perspective. Assume 150 people from a neighbourhood need to go from Point A to Point B. Compare the road space needed by three public buses that can carry them with the space needed by 75-100 personal cars to transport the same number of people. Imagine the street: three buses with a lot of free road space versus 75-100 cars with very little road space left. This is the reality of Dhaka's roads. And, this is not fair to the 90 percent of the city's daily commuters.

This is also simple maths justifying the utility of public transportation. An efficient public transportation system means people won't have to rely on private cars to go around. Yet, we don't embrace the idea of public transportation. There are a host of reasons for this. For the rising middle class, the personal automobile is the ubiquitous expression of social mobility—a moving family fortress that ensures safety on a hazardous road and showcases social status. About 4,000-6,000 newly registered cars and other motorised vehicles pour into the streets of Dhaka every month. Banks offer up to 90 percent of car loans to help clients buy their dream cars. The mushrooming car dealerships across the city are viewed as symbols of a prosperous society. Rapidly growing personal car ownership is the future of the city. And that future is filled with insanely congested streets.

The personal car is not the disease. The problem is how we embrace the personal car as a lifestyle. In a democratic society, how would the government discourage a family from buying a personal car when there is no safe, comfortable, and gender-friendly alternative for mobility? Singapore deploys draconian measures to make car ownership an impossibly expensive and bureaucratic process. Policies are in place there to encourage the public to utilise an efficient mass transit. Owning a car in Singapore is, in fact, a burden. In Dhaka, such measures won't work yet, because there are no comfortable alternatives. The Singapore model won't work because we have not yet figured out what kind of city we would like to develop. It is a deeply political and cultural question.

Second, Dhaka traffic is a multigenerational crisis, long in the making. Since the 1980s, when the capital city's urbanisation began to accelerate, we have ignored one of the key tools of creating a sustainable urban DNA: land-use planning. We allowed the city to become an untenable urban juggernaut, an infernal urban agglomeration, paying little attention to how the city's land could be developed with a logical sequence of use and zoning. What is land-use planning? A basic example begins with your family. Your children should be able to walk safely to their school in 5-15 minutes. This means each neighbourhood or a ward should have a number of good schools, so that a kid from Dhanmondi will not have to make an exhausting trip to school in Uttara. A good Segunbagicha school for Segunbagicha kids is good land-use planning. A city with a prudent land-use template reduces unnecessary road traffic, because people will not have to crisscross the city to reach their destinations.

Third, it is inevitable that a lack of coordinated urban governance would result in unregulated clogged streets. Much has been said about the lack of coordination among Dhaka's different urban agencies responsible for providing services. The streets of a megapolis like this city are too heavy a responsibility to be left to too many agencies. Cleaning the traffic mess in the city needs one tsar. That tsar needs to go to sleep thinking about solutions for Dhaka streets and wake up thinking about solutions for Dhaka streets. Period.

What are the ways forward? The hard truth is that if Dhaka's urban status quo continues, it is going to take a generation or two for the city to become sane before it bursts at its seams.

If we don't want to wait until Dhaka becomes Mohenjo-daro, the only way out is its decentralisation. Dhaka needs to stop being a monstrous primate city (greater than two times the next largest city in a country or containing over one-third of a nation's population). As the former World Bank economist Ahmad Ahsan studied, the economic costs of the capital city's overgrowth are a staggering 11 percent reduction in GDP, or about USD 32 billion in 2019. Ahsan wrote, "The urban population of Bangladesh has grown by nearly 10 times after independence, where as much as a third of which has taken place in Dhaka, whose population grew at an annual rate of 5.4 percent per annum between 1974 and 2017. Other large cities, though—Chattogram and Khulna with populations of more than one million—have grown at a far lower rate of 1.7 percent per annum."

Dhaka must stop being the only dream centre in the country. We need to lessen the city's burden. University education? Go to Dhaka. Heart surgery? Go to Dhaka. Establish a startup? Go to Dhaka. Why can't Sylhet become a national hub of healthcare? What's stopping Chattogram from becoming all things maritime? Why is Rangpur, with a new airport, not an industrial hub? Why can't Barishal be a new centre of high-tech industry, like Bengaluru, in the wake of Padma Bridge? Dhaka doesn't have to be everything. Being everything is killing Dhaka. Why are some ministries not located in other divisions?

Decentralisation is easier said than done, particularly when there is a pervasive but irrational political fear that being away from Dhaka—the centre of all powers—is to risk being forgotten, ignored, and diminished. Nobody wants to go outside Dhaka. The risk is too high. Time has come to fight this entrenched fear to save this city from the looming disaster. Dhaka must be decentralised. If necessary, the capital should be split between two cities. In an earlier column, I wrote, "Time has come when the idea of splitting the administrative functions of the capital into two cities should no longer appear absurd. On the contrary, the idea should rapidly sink in … Indeed, we should begin to incubate this idea in our political and administrative heads." I provided many examples of capital relocation across the world.

During Eid holidays, the insanity of Dhaka's streets disappears. That's because people return to their homes in other parts of the country. This "return" should be encouraged, facilitated, and incentivised by a policy of decentring Dhaka. Which ministry should we move to Rajshahi first?

Adnan Zillur Morshed, PhD, is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist. He teaches in Washington, DC, and serves as executive director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments