The city and its next generations

It is easy to be stressed out quickly in Dhaka. Roads are insanely congested. Footpaths are far from walkable. The air is unbreathable and the city is often a "smellscape." Life is not a piece of cake in Dhaka.

Yet there is magic in the city, if you can find it. There are unexpected oases of urban pleasure, if you look for them a bit hard. These are not just sites of joy, but also moments to critically reflect on issues that affect our lives in the capital city.

A few week ago, I was fortunate to be able to attend an intriguing art show, Art for Cause, at Drik Gallery in Dhanmondi. Even though the title sounded a bit clichéd, I was curious to know more about it. It was an art show organised by teenage students of some of Dhaka's English-medium schools to raise awareness of, and funds for, the distressed Rohingya children. Among these schools were Greendale International School, Green Herald International School, DPS STS School, Sir John Wilson School, Mastermind School, Scholastica, Wordbridge School, and Hurdco International School.

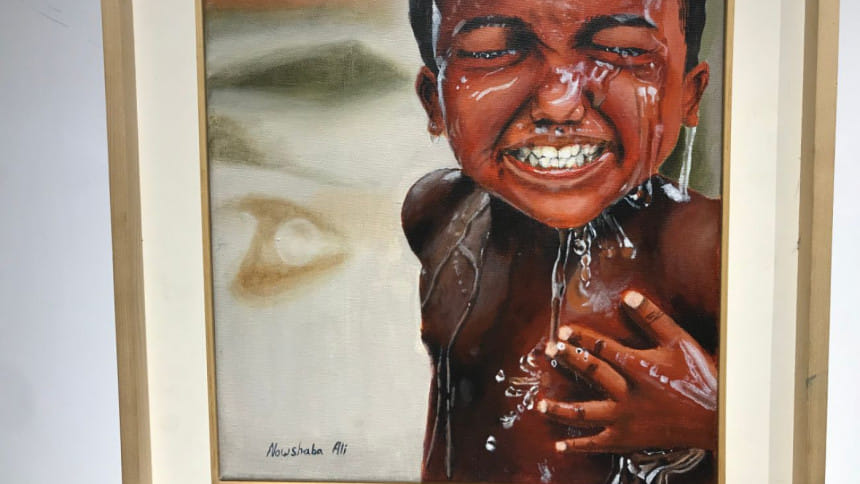

The show featured some really talented young painters. Ayman Omiyo Zahir's Contemplating Chaos—a pencil sketch of an enigmatic many-handed figure, as if trying to figure out our conflict-ridden world—was an apt metaphor for the refugee crisis that we are in now. Nowshaba Ali captured the endearing innocence of a Rohingya boy having a bath, his face gleaming with an inchoate happiness. Inspired by Edvard Munch's The Scream (1893), Emma Angela Gomes repositioned the haunted, screaming face with that of a frightened but calm Rohingya boy. Nuzhat Tasnim Mahbub's extraordinary portrayal of an elderly Rohingya woman, her wrinkled face suggesting a desperate wish to find final refuge, could actually be included in a world-class art exhibition. And, there were many perceptive paintings, chronicling the Rohingya exodus. All in all, it was a great show.

Yet the magic of the show was not in the heart-breaking beauty and social consciousness of the featured paintings. The show was both tragic and magical because it showcased how the young artists sought to shoulder an unfortunate burden of having to demonstrate their patriotism, their sense of social justice, and, most intriguingly, their loyalty to their motherland.

As I spoke with the energetic young organisers, it seemed that in Art for Cause they were battling on two fronts. First, they appeared to be genuinely interested in bringing the plight of the Rohingya children to the national spotlight. And, second, they were eager to shatter what they thought was a pervasive myth that afflicted them socially—the alleged apathy of English-medium students toward Bangladeshi issues. This entrenched myth has long propelled the popular binary imagination that Bangla-medium students tend to be patriotic and English-medium students are generally elitist and foreign-bound. Bangla-medium students celebrate Pohela Boishakh or 16th December and don patriotic outfits, whereas English-medium students gather at high-end coffee shops and discuss latest arrivals on Netflix.

The politics of linguistic patriotism received a huge boost in Bangladesh when UNESCO declared 21st February as the International Mother Language Day on November 17 in 1997. It was arguably the best homage to the very idea of the mother tongue. Earlier, in 1987, the then President HM Ershad enacted Bangla Procholon Ain (Bengali Language Implementation Act 1987), formally establishing Bangla as the official language in all administrative activities of the government.

The unfortunate and unnecessary politics of Bangla-English divide continued to plague public life in Bangladesh. However, the demand and appeal of English in the white-collar job market, particularly in the private sector, including multinational companies, UN projects, NGOs, and private banks, have been strongly felt.

The rapid proliferation of English-medium schools in Bangladesh since the 1990s epitomised two issues at the heart of the language debate: first, the lingering history of colonial patronage of English in creating a native elite and its post-independence reincarnation as a prop for upper-class status and, second, English as a marketable linguistic skill and a propeller of career success. Consider the typical advertisement of an English-medium school for student enrolment. As you would notice, it is often a misguided cocktail of the abovementioned issues and the social anxieties they cause.

Whether English-medium schools and universities tend to serve the needs of the wealthy and the elite, the myth of social exclusivity (and the affiliated prestige) has long defined them in the popular perception.

When I attended the art show at Drik Gallery I felt compelled to weigh in on the old Bangla-English debate that continues to complicate the Bengali self-image. As I spoke with Mohammad Naveed and Ayman Zahir, key organisers of Art for Cause, about their thinking behind the show and, in general, their vision for a future Bangladesh, I began to feel, even if prematurely, that the longstanding Bangla-English social divide was at a crossroads.

I felt tempted to think that we are witnessing the rise of a new generation of young Bangladeshis, who would like to voice their concern for environmental damage in Bangladesh, while at the same time demanding justice for the homeless Palestinians. They seem to have diminishing anxiety over seeing themselves both as Bangalis and global citizens. They seem at ease to love Jibanananda Das and Robert Frost concurrently.

Yet, the organisers of Art for Cause seemed to have been overburdened with the unnecessary task of having to defend themselves as conscious Bangladeshi citizens. The young students appeared too self-conscious of their purported complicity with the false elitism that English as a social tool promised. They don't need to defend themselves against the artificial binary of Bangla and English. The teenagers deserved better. They should be encouraged to master multiple languages, not just Bangla and English.

As they contemplate the future of Bangladesh, policymakers must consider and analyse the nature of new generations of Bangladeshis, who also view themselves as global citizens. How we foster them, nourish them, will determine the kind of Bangladesh we can build in the future. We must tap into this new, not-yet-fully-understood opportunity: the changing nature of our young demography.

Congratulations to the organisers of Art for Cause. It is another example of why we shouldn't give up on our city, our country. Dhaka may feel infernal but there is also hope.

Adnan Morshed, PhD, is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist, and currently serving as Chairperson of the Department of Architecture at BRAC University. He is also the executive director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at BRAC University and a member of the USA-based think tank, Bangladesh Development Initiative. His recent books include DAC/Dhaka in 25 Buildings (2017) and River Rhapsody: A Museum of Rivers and Canals (2018). He can be reached at [email protected].

Comments