Whence comes our culture of impunity?

These days, I assail myself with questions triggered by the everyday acts of thoughtlessness that I witness committed by the multitude around me everywhere, young and old, male and female. I witness them cutting in ahead of me in a queue I am in with other people, senior or not, whether at a bank counter, or a cash counter in a shop, or at a high-rise office block rudely jostling to get space in a crowded elevator. Attending an event of serious topical content or merely to watch a film or performance, my ears are relentlessly assailed: by the cacophony of people in the rear chattering away constantly in disturbingly high decibel levels, totally oblivious of the right of others to enjoy the show or listen to the serious discourse; by the boisterously loud conversations of groups in restaurants or public places without any concern for the right of others to enjoy their own space and food and company in peaceful quietude; by the public sharing of loud-voiced conversation of people using their ubiquitous mobile phones, conducting business transactions or romancing the person at the other end of the line.

I witness the countless acts of sheer indiscipline, blatant disregard of traffic laws, and utter disregard for safety of other users on the same road, whether by the dangerous behemoths that are the myriad buses, trucks and luxurious over-sized SUVs, by passenger cars, auto-rickshaws, motorcycles, rickshaws, cycle vans and human propelled carts, and even pedestrians jaywalking at will. My eardrums are agonisingly blitzed by the incessant blaring of horns by the vehicles around and behind me, even when it is eminently evident that the gridlock has everyone hostage in its relentless grip and road vehicles cannot metamorphose into helicopters.

I see and listen, helplessly, to the frantic gasping, hiccupping and wailing by turns, of the ambulances screaming for passage to ferry its patient, very likely in dire need of life-saving medical attention and recall how, nine years ago, a close and dear relative died in the ambulance carrying her to the hospital because it was stuck in the traffic jam for almost an hour and could not reach it in time for her to receive that emergency attention.

I am often exasperated, and sometimes angered, by the ineffectual presence of traffic cops who appear to be disruptively compounding the chaotic traffic flow by confusingly over-riding the programmed signals. At the same time I am also struck, quite often, by admiration at how just a few ineffectually empowered policemen try to cope with an impossible situation, often risking their own lives by physically stepping in front of the relentless, forward-surging avalanche of vehicles of all categories, trying to force it, like King Canute, to come to halt.

These everyday, inconsiderate actions of our populace demonstrate starkly the complete absence of a civic culture that defines civilised behaviour in any society. I recall imbibing the notions of responsible citizenship from my childhood, not merely enjoined by my parents and elders at home, but also having had to study compulsorily a subject called Civics in secondary school. Alas, apparently, those instructive voices and tools no longer exist.

We seem to have totally forgotten the cardinal principle of good citizenship: that citizens while demanding rights, in the public and private spheres, must also accept their own responsibilities, to the state as well as to fellow citizens. One's personal right cannot be at the expense of the equal rights of others. One's rights end where the rights of another commence; and just as one has a right to expect respect for his or her rights from others, he or she has an equal responsibility to respect the rights of others.

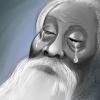

Assailed by a combination of all these experiences, I am overwhelmed by a sense of Weltschmerz (a feeling of world-weariness). I am forced to ask myself: how have we come to this sorry pass? This was not the culture and set of values that I grew up with, these were not the values that I imbibed from my forbears, parents and teachers. Why, and how, has all this changed so drastically, just three generations down the line?

Over a decade ago, I had written that not bringing to immediate justice the heinous crimes against humanity committed during the war of liberation was akin to ignoring the original sin that was bound to open the way for impunity besmirching our earlier long traditionally held mores. Condoning that original sin perhaps had laid the bedrock of the culture of impunity that was subsequently built upon by unscrupulous thugs of different varieties, some apparently enjoying political patronage, getting away scot-free with all sorts of criminal activity. All other crimes actually pale into insignificance when juxtaposed with that original sin. Why should any criminal fear the rule of law, or ordinary citizens have any respect for the institution of justice when these are commonly perceived as failing us?

The legal code and the system of temporal justice is built upon by the establishment of precedents and the application of the principle of stare decisis (that is, determining points in litigation according to precedent) to rulings handed down on previous related cases. Conversely, we may imagine, the validation of lesser crimes, if not in law but in people's minds, is also built on the analogical application of the stare decisis principle to ignoring, and by implication, condoning, the nation's original sin. If the most horribly unimaginable of transgressions is ignored or condoned, all lesser transgressions within and under that rubric automatically become equally, if not more, legitimate and acceptable, and the mutation of culture, whether civic or political, takes place. Once set, it takes generations to change.

Common sense dictates that a crime that is similar in nature, even if lesser in proportion or triggered by inflammation of primal passions, regardless of magnitude, committed by anyone, should remain a crime in the eyes of the law. It cannot be a prosecutable offence for one set of actors, and condonable for another. Otherwise, the core of the legal edifice is bound to become compromised, its statutes termite-infested. That will render respect for law and justice tenuous, and transgression of the rule of law condonable. We need to mercilessly question ourselves: is this how we have encouraged the inevitable growth, and enlargement, of this pervasive, mindless culture of impunity?

Faulkner in his Requiem for a Nun, had said, famously: "The past is never dead. It is not even past." As long as the truth is not revealed in its entirety and faced squarely, catharsis will elude the nation, as will a chance at expiation and reconciliation. The truth can never be addressed in segments, selectively; it must be addressed holistically.

But perhaps all is not yet lost, I reassure myself. This flicker of hope is kindled by the recent image of a brave officer in uniform, dedicated to bringing discipline to a chaotic traffic, firmly but respectfully positioning himself squarely in front of a very officious-looking vehicle that was very clearly transgressing the law. This image is as iconic as another similar image seared in my mind since 1989: of a lone man, standing in front of a convoy of tanks on a road leading to Tiananmen in Beijing, bringing that convoy to a grinding halt, even if fleetingly at that time.

In the end, it will be akin acts of brave citizens, individually and collectively, mustering courage to stand up and make such statements, willing to incur the wrath of the all-too powerful state, to redress what has gone so awry and wrong. The state of the State, for its good or bad, is always in the hands of its citizenry.

Tariq Karim, a former career diplomat and academic, is currently Visiting Fellow at BRAC University.

Comments