Defining Tajuddin's place in history

Tajuddin Ahmad was the one who filled a crucial void in leadership during Bangladesh's most important nine months in 1971 after Bangabandhu had been taken prisoner by the Pakistani army. A just question, therefore, is, with Bangabandhu's absence, whether Bangladesh's independence in such a short time would have become a reality had it not been for Tajuddin Ahmad's timely rise to the leadership challenge, his organisational acumen, statesmanship, political and diplomatic wisdom.

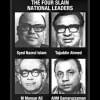

Like Bangabandhu, Tajuddin was pushed into irrelevance in the political discourse after his life and that of three other national leaders were brutally cut short on November 3, 1975. With the Awami League's return to power after the reinstatement of democracy in the 1990s, Bangabandhu's place was duly restored in contemporary discourse but Tajuddin remains somewhat underappreciated in political circles.

***

Tajuddin Ahmad had always had a strong opinion about all that mattered to him, and a clear socialist vision for the country he would later help liberate.

To him, an independent country meant one free of exploitation, hunger and poverty. "Let there be a new world for the hungry and suffering millions of Bangladesh where there will be no scope of exploitation. Let us pledge for freedom from hunger, disease, unemployment, and illiteracy," he told the fighting nation the day after the Provisional Government of Bangladesh was formed.

He was an ardent proponent of the idea of self-reliance. Once, while he was the finance minister of independent Bangladesh, he did not, at first, want to meet the chief of the World Bank, which he saw as an apparatus of exploitation of the global capitalist elites. When he finally did, he all but rejected the Bank's offer of assistance, refusing to go along with the government's apparent shift towards the West, even if it meant his being removed from the cabinet.

Tajuddin's exit from the cabinet came at a time when the nation was undergoing a famine apart from other political and social turbulence. Before his resignation, he presented his last and the nation's first Five-Year Plan, which reflected his philosophy of self-reliant development. The plan emphasised on educating the youth and students, eradicating poverty by developing physical and human infrastructure.

He was the kind of man who stood out in a crowd because he never hesitated to disagree when he felt it was the right thing to do and make his dissent known. When Bangabandhu decided to form BaKSAL by abolishing the multiparty system, for example, he respectfully demurred—a rarity among our politicians. However, the loyalty to his leader superseded anything in Tajuddin Ahmad's life, as evident by the fact that he joined BaKSAL despite having serious reservations.

Even before the War of Liberation began, Tajuddin earnestly wanted Bangabandhu to lead the struggle by going into exile, as the Pakistani military had launched its genocidal crackdown on Bengali civilians, but Bangabandhu believed that an elected leader does not run from dangers and was soon arrested. When the Bangladesh government in exile was formed in Badyanathtala, Kushtia, he renamed the place as "Mujib Nagar" in honour of his absent leader; he welcomed foreign journalists "on behalf of the government of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman." After independence, he spearheaded the diplomatic war to secure the early release of Bangabandhu from Pakistan's prison.

***

Tajuddin's stint as the wartime prime minister was marked by his ability to keep several factions—within and outside his party and the Mukti Bahini—focused on the cause of liberation.

It was not an easy feat. In particular, as Professor Emeritus Serajul Islam Choudhury argued in a 2015 speech, Bangladesh Liberation Force (BLF)—also known as Mujib Bahini—sowed a rift between Bangabandhu and Tajuddin.

While Tajuddin, both during the war or in its aftermath, favoured leftist organisations, some of which were not associated with Awami League directly, drawing suspicion from a section of his own party, he never failed to pass the test of loyalty, dedication and commitment despite being held to higher standards.

The fact is, both Bangabandhu and Tajuddin have distinct places cut out for them in history, for the different roles that they played, and any attempt to place them against each other or undermine one in favour of the other will be a misguided one. Unfortunately, this is exactly what seemed to be the case for long.

Was it not possible for our successive governments, especially the ones led by the party he belonged to, to recognise Tajuddin in a manner befitting his stature without risking the legacy of Bangabandhu being undermined? He may not have been treated with the respect and grace the nation owes to him, but his legacy will surely be remembered as a chapter of national history filled with honour, integrity and rectitude.

Nazmul Ahasan is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments