Lessons of consent and critique from Ferdousi Priyabhashini

I woke up on March 6 and was devastated to hear that Ferdousi apa, Ferdousi Priyabhashini—the famous Bengali sculptor, survivor of wartime rape and a protagonist campaigning against it in Bangladesh—had passed away. I was being asked to write a piece in remembrance of her life and work. And I haven't been able to write a piece till now. This is because for me Firdousi apa was not only a survivor of the rape by the Pakistani army and local East Pakistani/Bengali collaborators during the war of 1971. She was a spriit who had "unmade patriarchy" (to quote Dina Siddiqi—communication via email) through her life.

Following AHM Kamruzzaman's announcement on December 23, 1971 that all women raped during 1971 would be referred to as birangonas (meaning brave or courageous woman—the Bangladeshi state uses the term to mean war-heroine), thorough research of Bangladeshi newspapers after 1971 shows how various women were featured acknowledging that they had been raped by the Pakistani army (first explored in my book The Spectral Wound. Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh War of 1971). Bangladesher Swadhinota Juddho Dolilpotro (Documents of Bangladesh's Independence War), edited by the renowned poet Hasan Hafizur Rahman and other eminent historians and academics, also contained five narratives of raped women. We are obviously unable to explore here the conditions under which these women spoke.

In 1992, when the photograph of three landless women (from western Bangladesh) was published on the front page of all leading Bangladeshi newspapers, it became a visual testimony of how women raped during 1971 were seeking justice in the 1990s against the collaborators. Although they did not speak at the event, the photograph brought the topic of wartime rape back into the Bangladeshi press in the 1990s. So throughout the 1990s, various oral history projects sought to record the testimonies of birangonas. Newspapers also reported innumerable testimonies with portrait photographs accompanied by headings like "Birangona Bokul in the mental hospital" or "Birangona Morjina is leading a life of poverty." The birangonas here look straight into the camera, erect, cautious, and cut off from their family members, everyday surroundings and activities. The important question to pose at this point is: What makes the birangona woman visible and audible at certain historical junctures? The 1990s narratives of women's wartime-rape did not emerge because of the sudden end of censorship, because the women "broke their silence," or because society came to terms with its traumatic past overnight. The publication of a photograph of the earlier mentioned birangonas and their mute testimony reignited the question of the role of the collaborators in the sexual violence of '71.

Firdousi apa was part of one of these oral history projects and I was introduced to her by my feminist friends in Dhaka or her colleagues working in the organisation she was employed at in the late 1990s. She asked me to visit her and in her beautiful home reflecting her artistic and aesthetic sensibilities she introduced me to her work and, in due course, her life. I did not ask her any questions as I knew other friends were working with her and I did not want to transgress ethical boundaries around research. [see Akhtar, Shaheen. 2001. Firdousi Priyabhashini: ekok nari (Firdousi Priyobhashini: the lone woman); Narir ekattor o juddho poroborti koththo kahini (Oral history accounts of women's experiences during 1971 and after the war) (eds) S Akhtar, S Begum, H Hossein, S Kamal and M Guhathakurta eds. 57-79. Dhaka: Ain-O-Shalish-Kendro (ASK)]. She however expected me to ask her questions. In the absence of the question answer setup, she would instead tell me in "fragments" the noxiousness that had descended on her life during and after the war. This was a time when she hadn't gone public about being a birangona and instead her experience was being written anonymously.

Within these fragments two accounts stand out for me most strongly. In one instance she talked about how:

"If the end of your finger is touched without your consent, the finger would burn. Imagine how it would feel if it is the rest/whole of your body."

For me this was an even more powerful narrative of her experience of wartime rape than an explicit narrative about it. In a moment she had reminded me of one of the most poignant ways of understanding consent and the experience of wartime sexual violence. Another significant "fragment" is her idea of hypocrisy prevalent in various societal instances after the war which goes against the idea of shame and stigma easily bandied around by those trying to explain wartime rape. As she said:

"Lojjashorom to shomajer je tara amake dayi kore amar ja hoi tar jonno. Amar kisher lojja?" (Society should be ashamed for blaming me for what happened to me. Why should I be ashamed?)

After the war she had to move constantly to avoid these societal hypocrisies thrown at her and her family. And so not just 1971, she "unmade" patriarchy through her continuous struggles against which she stood up each and every time. Her strength—which I learned from enormously—reminds me of Rukshana, a lower middle class birangona who has chosen to remain anonymous. Referring to the rapes by the Pakistani army in 1971, Rukshana powerfully said to me:

"They might have fulfilled their own lust but they did not get anything from me."

In the late 1990s when Ferdousi apa decided to tell her own story of wartime sexual violence instead of listening to a re-enactment of her account, the first and poignant revelation was made to her children who did not know anything of their mother's past. She publicly acknowledged that during 1971 she had been raped during the war by the Pakistani military and also various Non-Bengali and Bengali/East Pakistani collaborators, all of whom sought to take advantage of her vulnerability as a woman solely fending for her family. As a birangona from a middle class background, her testimonies and photographs have been central to various national commemoration programmes on '71. She dismantled the prevalent stereotype that all birangonas are ashamed and invisible as a result of their rape. In my book I argue against this inherent idea of silence, shame and stigma of wartime sexual violence and instead show the political economy in which shame, stigma and silence is invoked.

The documentary film Women and War (2000) made by my friends—the famous and late Tareque Masud and Catherine Masud—in fact illustrate the kinds of frameworks within which women subjected to sexual violence have rebuilt their lives. For Mazlibala, a poor, landless tribal woman, the very fact that people have known that there was an attempt to sexually violate her is itself like being sexually violated. Ferdousi Priyabhashini juxtaposes her present valorisation as a "protagonist" birangona with the contempt and social abandonment that she encountered after the war.

"I work with and sculpt the bark of trees as they signify to me the abandoned, like I was after 1971—abandoned, ridiculed, humiliated and treated with contempt". (Ferdousi Priyabhashini, Women and War).

When Ferdousi Priyabhashini gave a speech on her 1971 experiences at a 1999 ceremony honouring her as a birangona, she said, "The truth is tough". At the Tokyo Tribunal in 2000 she met a ninety-year old Korean "comfort woman" who felt happy and relieved after delivering her testimony. She said, "you, me, we are the same, our pain is the same" (Hossain 2009: 12). [See Hossain, Rubaiyat 2009 'Trauma of the Women, Trauma of the Nation: A Feminist Discourse on Izzat'. Unpublished paper presented in the Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice, 30-31 July, 2009. Organised by Liberation War Museum. Dhaka, Bangladesh].

As a protagonist birangona she has been able to put forward various demands towards the government. In a workshop that I organised with Dr Meghna Guhathakurta and her colleagues at Research Initiatives Bangladesh in November 2016, Ferdousi apa came and filled the room with her affection and smile. At the same time she was critical of the way in which activists and journalists assumed a certain horrific and traumatic narrative of the birangona. She reminded us of the innumerable times she has been asked by journalists to make her room dark and dreary so as to get the right "background" when interviewing a birangona.

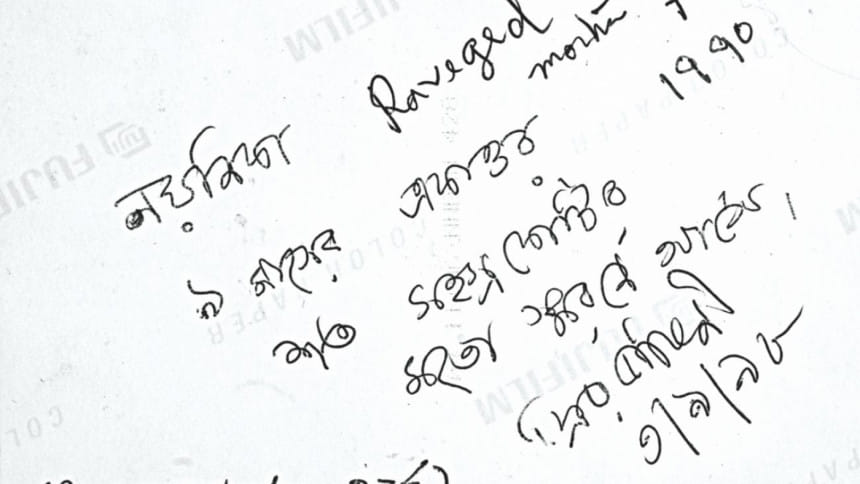

I did not interview her but her fragments, her affection, her warmth taught me a lot. As I honour her legacy and all that came before and after her, I treasure the sculptures I have of hers and the following note that she gave me in 1998 before she had publicly acknowledged her experience. In the note she said:

Nayanika: Ravaged Mother 1971 (1990). Noy masher ekattor soto sohoshro kotir moto shorone ashe. (The 9 months of 1971 comes back to me thousands of times) Priyabhashini (3/9/98)

This memory and the legacy she leaves behind is the tough truth for all of us.

Dr Nayanika Mookherjee is an Associate Professor (Reader) of Social Anthropology in Durham University and author of The Spectral Wound. Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh War of 1971. (2015 Duke University Press; 2016 Delhi: Zubaan). She has published extensively on Anthropology of violence, ethics, aesthetics and Transnational adoption. Her current research is on the war babies and transnational adoption of the 1971 war.

Email: [email protected]

Comments