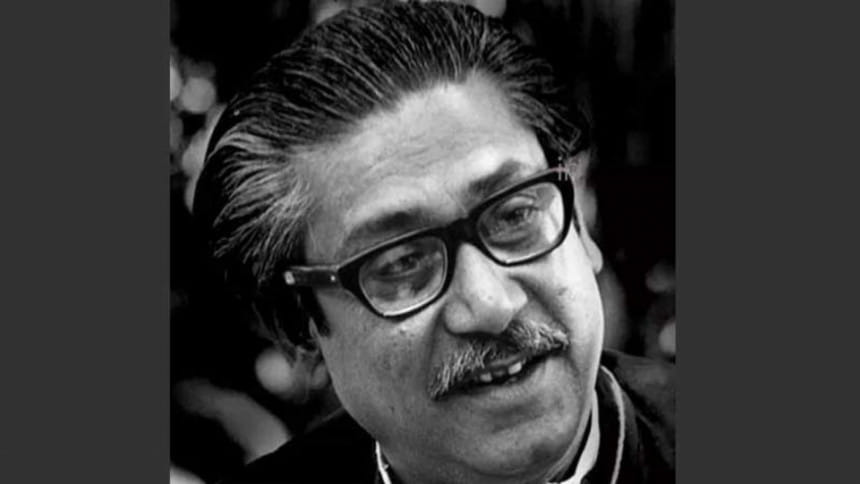

An album on the poet of politics

My first impression of Bangabandhu dates back to around the mid-sixties. A helicopter service had been in operation between Dhaka and Faridpur for a couple of years by then. A corner of the Tejgaon Airport was designated as a heliport. I had just disembarked from a helicopter arriving at Dhaka from Faridpur. As I was approaching the small terminal building, and still some distance away from it, my eyes swung on to Bangabandhu seated majestically with what felt like an air of defiance.

The majestic aura was the signature of his leadership stature attained through sacrifices and frequent imprisonments. The defiant mode he reflected was an indignant response to the manner in which the authority had stalked his footsteps.

He was waiting to take the flight to Faridpur on his way to Gopalganj, his birth place on one of his rare respites between periods of incarceration. My eyes remained transfixed on him till he ambled across to the helicopter with a spring on his feet. For soon he would be back into the pure charm of his first home, evocative of tree-lined ponds he had bathed in, in his childhood days. He would, I reckoned, reminisce about it, all soaking up fresh energy to attend to his wider call of political duty. His long walks through villages and the big rallies he inspired since his adolescent days right up to the defining 1970 elections were simply legendary.

One of his hallmark grassroot connections was the amazing intimacy with which he nurtured and sustained rapport with masses. He knew by name the presidents, general secretaries and other office bearers of Awami League Thana committees, and could recite them when he needed. You have to passionately love people and care about their personal welfare to remember them with such ease. Actually, such a trait would have effectively meant keeping track of thousands of names all over the country. He did it as a true a leader of the people.

Another image of his etched on my mind can be traced to 1973. In the inner lawn of the old Jatiya Sangsad at Tejgaon—not before the eighties would the Parliament Bhaban as we know it today be ready for use—I saw him seated upright making points to a group of people prizing every moment of the experience.

Speaking of his charisma, a retired secretary recalls an incident in Bangabhaban, seemingly flustered now as he was then by it in real-time. Along with a senior colleague who worked at the president's office he was walking inside the Bangabhaban. Suddenly, they noticed that Bangabandhu accompanied by the then president Abu Syeed Chowdhury was coming in their direction. And as the two VVIPs were passing them by, they summoned enough courage to greet them with customary courtesy. Bangabandhu reciprocated it with his baritone, leaving the ex- secretary and his senior colleague experiencing as though "a current had just pulsated through them"!

A relative of mine studying at Mymensingh Agriculture University immediately following the birth of Bangladesh would share his experience of discovering "something special" in him. As Bangabandhu was being given a tour of the campus, by the university authority, my cousin, glued to the proceedings, would marvel at the flashes of his inspiring finding.

I remember having tuned into Akashbani and heard the news reader breaking the news of his assassination with the closing words: "Unki ek sammohini shakti thi" ("He had a hypnotic power").

He was a humanist and large hearted. When some Bangladeshi politicians who had collaborated with Pakistan occupation forces were put in jail, Bangabandhu would send succour to their families.

Politically, he was so principled about the course East Pakistan should be taking that he spurned the notion of the so-called two-unit system indicating "parity" between the two wings. He could see through the bluff intended to deter the movement against disparities. It was then about to heave into a struggle for autonomy.

Admittedly, however, he drew criticism for having switched over to one-party rule in a break with AL's consistent legacy of working in a multi-party democracy and upholding it. Future historians will judge him on that but I can add two points to share with the readers as to how my mind works on the issue.

Let me put on record a fact I came to know as an officer of the Bangladesh Bank: the Annual Report of the central bank for fiscal 1974-75 had come to the conclusion that the economy was evidently on an upswing based on positive indicators on major macro-economic parameters. But after the heinous assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, along with most members of his family, the coup leaders issued a white paper claiming the exact opposite of what the Bangladesh Bank Annual Report mirrored as a positive state of the economy. I had already distributed the annual report to listed addresses including the Bank of England. So, the authentic word had got around.

The Father of the Nation wanted to put smiles on the faces of dukhi manush, which is difficult to translate aptly into English except to say the phrase referred to people in distress or the disadvantaged ones. In fact, it was a part of his mission to create a Sonar Bangla. But his life was cut short, allowing him less than three years to pursue his mission.

The national economy is firmly set on a growth trajectory and the country's prospects as one of the select group of the next genre of emerging economies are widely talked about. Now Bangabandhu's daughter Sheikh Hasina has the precious opportunity to fulfil her father's dreams.

A final word. Whatever his critics may say, one thing is for certain: Bangabandhu's creation is Bangladesh, and as long as we live and breathe in it, we must be grateful to him and keep him above controversy.

Shah Husain Imam is adjunct faculty, East West University, a commentator on current affairs and former Associate Editor, The Daily Star. Email: [email protected]

This article was originally published on March 17, 2017 in The Daily Star.

Comments