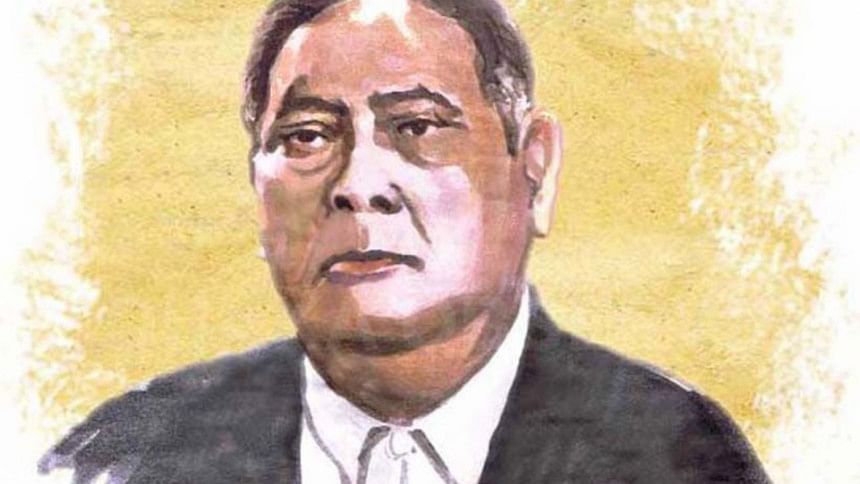

Sher-e-Bangla: A natural leader

Dr TG Percival Spear of Cambridge University divided leadership into five types: (1) natural, (2) charismatic, (3) rational, (4) of consensus, and (5) by force. According to him, the natural leader is selfless; he is, in fact, not interested in leadership. He exerts himself to the best of his ability and with all the sincerity and devotion under the sun without any expectation of reward. Because of his sincerity, he is able to establish a personal bond with his followers. Generally, the cause throws up such a leader—he takes to it like a duck to water.

Dr Spear cites Napoleon Bonaparte as an outstanding example of a natural leader; the imprint on the sands of time of this "Child of Destiny" can never be erased. Sher-e-Bangla AK Fazlul Huq, the indomitable champion of truth and justice, was also an out-and-out natural leader. It is true that he was not fated like Napoleon to eat his heart out in exile, or to bury himself during the closing years of his life in bitter memories of a stirring past. In a sense, Napoleon had been fortunate in his death; he had been spared the torment of brooding over the ruins of his ambition. But Sher-e-Bangla did not fade away gradually. He died, as was proper, in the fullness of his glory. Like Napoleon, he was also a patriot, an idealist, a man of action, a dreamer of dreams.

A review of his career reads like a romance: it seems unbelievable that a man so daring, so adventurous, so bold, so reckless of consequences, and yet so intensely practical, should have arisen in this benighted land of ours. Yet, a study of his life will show that "the elements" were: "So mixed in him that Nature might stand up / And say to the world: 'This was a man'!"

Like a genuine natural leader, he had always been wedded to his ideals and, in his ardent desire to realise them, he unhesitatingly lighted upon truths that "perish never." He never bothered about creating any effect. He took up a cause if it came naturally to him, and always worked for it with genuine sincerity and indomitable courage, befitting a natural leader of the first order. His towering frame overshadowed everyone and everything around him. But more, much more, than his physical charisma was the vision and the deep humanity that came through and left an indelible impression.

A man with amazing foresight, he had the courage and conviction to demand a separate Bengali Army in British India. In a letter addressed to Sir John Herbert, the Governor of Bengal, on August 2, 1942, he wrote: "I want you to consent to the formation of a Bengali Army of a hundred thousand young Bengalis consisting of Hindu and Muslim youths on a fifty-fifty basis. There is an insistent demand for such a step being taken at once, and the people of Bengal will not be satisfied with any excuses. It is a national demand which must be immediately conceded."

In February, 1943, he made a statement in the capacity of chief minister of Bengal on the floor of the Bengal Legislative Assembly regarding the then government's policy on Midnapore Affairs. Sir John Herbert did not like the statement and, in a letter written to Sher-e-Bangla on February 15, 1943, he demanded: "I shall expect an explanation from you at your interview tomorrow morning of your conduct in failing to consult me before announcing what purports to be a decision of the government."

The letter very naturally angered Sher-e-Bangla and, in a befitting reply sent on February 16, the Tiger of Bengal roared: "Dear Sir John…I write to say that I owe you no explanation whatever in respect of my conduct in failing to consult you before announcing what, according to you, is the decision of the government, but I certainly owe you a duty to administer a mild warning that indecorous language such as has been used in your letter under reply should, in future, be avoided in any correspondence between the governor and his chief minister."

What is more, he did not even hesitate to rebuke the journalists of his time for their passive role and cowardice. Reminding them of great dare-devil journalists like Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Motilal Ghosh, and Surendra Nath Banerjee, he declared on the floor of the Bengal Legislative Assembly on February 27, 1944: "They were lions in their own days and we have the descendants of the lions of Indian journalism in our midst today. But the difference between the two classes of lions is very significant. Those were lions whose roars used to reverberate from Bengal across the seven seas to the homes of the British nation, but in the case of the present lions, they are as docile as lions in a circus show. The roar of the lions of old used to make thrones tremble, but most of the present lions only know how to crouch beneath the throne and wag their tails in approbation of government policy." No other politician in the history of this subcontinent ever had the guts to scold journalists in such a forceful language.

But it was not only his indefatigable spirit and indomitable courage which marked him out from the average run of leaders in the unusually brilliant and colourful Indian political firmament; his brilliant wit and remarkable sense of humour, occasionally ably supported by his thorough grasp of mathematics, together with an unparalleled ability to gather up complexity and transmute it to simplicity, also endeared him to the masses.

When Dr Nalini Ranjan Sircar, himself a renowned parliamentarian, urged the chief minister to change the angle of vision regarding a particularly ticklish issue, Sher-e-Bangla promptly replied that it was not his angle of vision but that of the honourable member which needed a change. With his inimitable sense of humour and superb command of mathematics, he retorted: "The angle of vision of my esteemed friend may be either acute or obtuse, but never the right angle."

A highly skilled parliamentarian, Sher-e-Bangla managed to keep cool, calm, and collected in all difficult situations—even when irritated or annoyed to an extent beyond measure. While facing a bitter opponent and critic during a budget session in the Bengal Legislative Assembly, Sher-e-Bangla was awfully irritated by the peculiar gestures and caricature of a hostile member. The member was urging the chief minister to rise to the occasion and face the music. He was harping on the same tune, and it was enough to try the patience of a saint.

Sher-e-Bangla interrupted and said: "Mr Speaker, I can jolly well face the music, but I cannot face a monkey." All were dumbfounded as none expected such a crude remark from a seasoned politician like Sher-e-Bangla. The member concerned demanded immediate apology and withdrawal of the objectionable and unparliamentary remark of the chief minister. But, cool as a cucumber as he always was, our beloved hero with his brilliant parliamentary skill replied: "Mr Speaker, I never mentioned any honourable member of this House. But if any honourable member thinks that the cap fits him, I withdraw my remark."

This was our beloved Tiger of Bengal—a friend, a companion, a colleague, a leader of the suffering millions.

Syed Ashraf Ali, who died in 2016, was a former DG of Islamic Foundation. This is an abridged version of an article originally published on October 28, 2008 in The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments