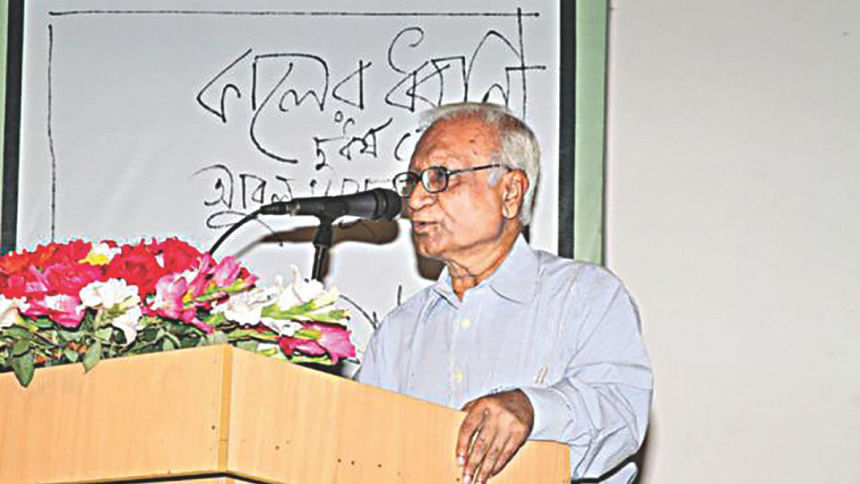

Serajul Islam Choudhury - Our Leading Intellectual and Inspiration

He confronts, challenges, and combats the world with words. But his words become more than words. They morph into weapons in our struggles against oppression and injustice. For him, of course, writing is fighting. But, then, he is more than a combative writer. He is, first and foremost, an intellectual—our leading public intellectual in Bangladesh—one whose entire work is deeply informed by the question of social revolution in the interest of people's emancipation. And, for him, it's "the people, the people alone," who constitute "the motive force in the making of world history." I'm speaking here of none other than Serajul Islam Choudhury, one of the most productive and prominent writers in the Bangla language today. And I cannot resist saying with pride that he was my own direct teacher in the English Department, Dhaka University. Today—June 23—marks his 82nd birthday.

Serajul Islam Choudhury has already been known in a number of ways: as a literary and cultural critic, historian, sociologist (of the everyday), political commentator, essayist, columnist, translator, even as a fiction writer, editor, organiser, activist, and, of course, as an educationist, as an outstanding teacher of English literature, even as our "nation's teacher." The range and richness, the scale and scope, of his work are simply phenomenal, even dizzying. He has authored more than a hundred books and countless articles, hitherto collected only incompletely in eight large volumes. Yet one may chart out the broad but interconnected terrains of Choudhury's work thus: society, history, culture (and literature), and politics.

But, regardless of how Choudhury is identified and whatever his area is, in almost every instance, it's the task of the intellectual that he has carried out with exemplary force and fervour, with commitment and conviction. In other words, over more than five decades now, he has continued to intervene, investigate, and interrogate, fiercely mobilising his knowledge and intellect and passion, all in the interest of radical social transformation. As an intellectual—

whose rootedness in his own land remains connected to his robust internationalism—Choudhury characteristically speaks the truth to power, while urging us to say "no" to the vulgarity and violence of the existing system—to the tyranny of capital in particular. He thus turns out to be a veritable voice of social conscience.

Like the great Latin American intellectual and writer Eduardo Galeano—one of whose ground-breaking works is instructively titled We Say No—Choudhury fervently relays the message that reality is not our destiny but a challenge. His latest collections of essays—Paa Raakhi Kothay (2018) and Ogrogotir Shartapuran (2018)—are superb examples of an intellectual's power of negation and affirmation as well as his vision of a world where private ownership is decisively replaced by social ownership. In these engaged and politically charged cultural works—acutely attentive as they are to the otherwise-ignored details of our everyday social life—Choudhury once again appears as our major anti-capitalist, anti-colonial, anti-communal, and anti-patriarchal writer, committed as he is to the cause of socialism and human emancipation.

***

Serajul Islam Choudhury has broken ground in numerous areas. It's impossible to evaluate the entire range of his contributions in a short piece like this one. One can only touch upon a few areas of his interventions. Indeed, he has almost singlehandedly inaugurated a mode of contemporary Bangla criticism in which the literary, the ideological, the political, the social, the historical, the economic, and the cultural vibrantly intersect, making the point that nothing human is alien to his work. As a natural inter-disciplinarian—matchless as he is—he expands the horizon of our engagement with the word and world in order to change it. All this is evident in his treatment of some of his favourite themes such as the questions of nationalism and national liberation in Bangladesh; our bankrupt mainstream political culture; the culture of our middle class; the pitfalls and possibilities of left politics in the country; the question of class struggle and the burning need for revolutionary politics against capitalism and imperialism; the questions of gender and minorities in Bangladesh; and, above all, the questions of equality and emancipation. Choudhury's own journey as a writer from his relatively early work Swadhinatar Spriha o Shyammer Bhoy (1988), through Bicchinotay Ossomoti (2014), to Oggrogoitir Swartopuran (2018) has been that of a passionate intellectual dwelling on the aforementioned themes, an intellectual who thereby has also been tirelessly fighting for the cause of the oppressed in the country—peasants, workers, women, and minorities.

Not much has been written about Choudhury's powerful interventions in the field of what is called "world literature." His readings of Indian epics, Kalidasa's Sakuntala, Greek epics and tragedies, Shakespeare's tragedies and his women characters, Milton's Paradise Lost, eighteenth-century English novels, the nineteenth-century French novelist Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary, and the great Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina—not to mention his readings of the trinity of the modern novelists such as Conrad, Forster, Lawrence—have all been landmark interventions that exemplify the power of observation and analysis as well as the commitment of an intellectual to raising questions about unequal power relations and oppressive ideologies that variously play out in the field of literature itself. One can, I think, say the same thing about his sustained discussions of every major Bengali literary figure, ranging from Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Vidyasagar, to Madhusudan and Bankim, to Rabindranath and Sharatchandra, to Jibananada and Nazrul, to mention but a few. Indeed, no one has so powerfully and consistently questioned the literary establishment as Choudhury has done, running against the grain of today's dominant culture of both deification and demonisation.

The works I've mentioned above can certainly be reckoned as Choudhury's political works of culture. And, for him, culture—by which he designates the totality of lived human experiences and practices—constitutes one of the most fundamental sites of class struggles, antagonisms, and resistance. Without recreating it in favour of the oppressed, politics itself remains vain and empty and surely anti-people, as Choudhury suggests in many of his works.

Finally, on relatively personal registers: I have not only been Serajul Islam Choudhury's direct student but have also worked closely with him over the years. I've seen how he has come to embody and exemplify the three beautiful human qualities I myself value the most: sense of compassion, sense of justice, and curiosity. And I've seen how he has lived fully, intensely, creatively. Even at 82, he tirelessly writes and publishes, edits, lectures, gives interviews, organises events, and interacts with students and writers and activists from around the country. Last year, his role in commemorating at the national level the centenary of the October Revolution of 1917 simply proved to be exemplary, while it is well-known that he was actively involved in a number of progressive social movements in the country. Work for him is both love and struggle made visible. On his 82nd birthday, I dedicate to him these lines by none other than the great Marxist playwright-poet Bertolt Brecht: "Canalising a river/ Grafting a fruit tree/ Educating a person/ Transforming a state/ These are instances of fruitful criticism/ And at the same time instances of art." I think my teacher Serajul Islam Choudhury is also an "artist" in the revolutionary sense, and he continues to remain an inspiration in our struggles for creating a world better than this one.

Azfar Hussain is Vice President of US-based Global Center for Advanced Studies and Associate Professor of Liberal Studies/Interdisciplinary Studies at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. He is currently Summer Distinguished Professor of English and Humanities at the University of Liberal Arts-Bangladesh (ULAB).

Comments