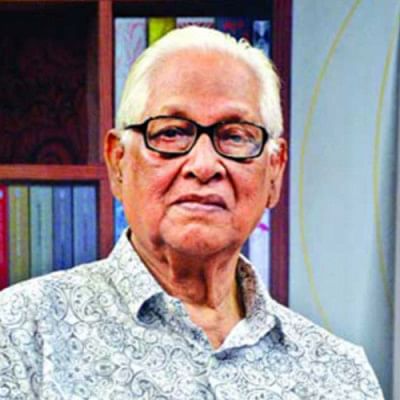

A tribute to Mustafa Nur-Ul Islam

For most people who live to be 90, life is usually one long, painful journey troubled by debilitating illnesses or loss of mobility or memory, or both; they have to depend on others for the simplest of tasks like pouring a glass of water or turning in bed. National Professor Dr Mustafa Nur-Ul Islam, who died on May 9 at the age of 91, was an exception however. Barring the last six months or so, he lived quite an active life, doing things he loved to do—reading, writing and anchoring a popular discussion programme on television. He couldn't climb stairs and needed help to reach the third-floor studio of ATN Bangla, which aired his weekly Kothamala, a remake of the hugely popular Muktadhara on Bangladesh Television (BTV) of the 1980s which ran for ages. A wheel chair was on hand, pushed gently by a kind and youthful attendant, whenever he needed it. He used it with a bit of embarrassment though, as if he was not being true to his energetic and vibrant self.

It was in ATN Bangla that I saw him for the last time, six or seven months ago. Despite the fatigued look on his face and puffiness under his eyes, he exuded his usual charm. He had an incredible memory and could recount events from the 1940s or 50s as if they had taken place just the other day. He was an eloquent speaker and could start a meaningful conversation on any topic that happened to suggest itself, from the Charyapad to Charlie Chaplin's silent movies to his relationship with Bangabandhu whom he called Mujib Bhai. He talked in a clean, crisp and powerful Bangla that showed his sophistication and verbal flair. He also had a great sense of humour and a ready stock of anecdotes to enliven any conversation.

The last Kothamala episode I took part in was on the power of silence. His choice of free-standing topics such as this was a challenge to the speakers, who tried hard to come up with talking points. Dr Islam didn't much help, except providing some clues on which to build their discourse. Whether one was up to the mark, he looked on with a benign smile, silently encouraging the speaker to go on. He clearly knew how to bring the best out of people, even those who were not comfortable speaking in front of a camera. No wonder he was an admired teacher with an outstanding track record.

It was in the early 1980s—about the time he launched his Muktadhara on BTV—that I got acquainted with him. I had gone to attend a seminar organised by the department of Theatre in Jahangirnagar University. Dr Islam, who taught in the department of Bangla which he had helped set up, was the chair of a session where I spoke on Bertolt Brecht and a little-known play of his, The Exception and the Rule. After the session was over, he took me aside and asked me if I could lend him the book which I was carrying. I was flattered. He was already a celebrity for his scholarship and eloquence, and I believe also for his good looks and his nearly six feet height. As we drank tea and munched on crunchy samosas, he told me his ideas about a literary magazine that would set a standard of critical discourse in our country.

The magazine was Sundaram which he worked hard to bring out quite regularly despite heavy odds for more than two decades. It indeed became a model for many such magazines that followed. It was his friendly charm that made distinguished writers and scholars and young researchers alike to contribute on topics he would choose carefully and well in advance. Over the years, I wrote nearly half a dozen articles and twice the number of book reviews for Sundaram—all because I couldn't say no to him, and because of the challenge of writing for him, who was an astute editor and a discerning reader.

It is hard to believe that the man who was such a vital presence in the country's educational and cultural scene for the last seven decades is no more. He was there in all the key moments of our country's history, either as an active participant or a facilitator. Dr Islam was there when the language movement of 1952 first proclaimed our cultural independence from Pakistani neo-colonialists. He was a participant of the famous "Kagmari Sommelan", a hugely successful political event which also had a cultural event on the sidelines, spearheaded by the revered Maulana Bhashani in 1957; he was there when the youth began their decade-long struggle to oust the Pakistani regime in the early 1960s, articulated by the back-to-back movements against the ban imposed on Rabindranath Tagore's songs on the radio and the blatantly discriminatory educational policy of Ayub Khan. He was an ardent supporter of the six-point programme launched by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1966, and the subsequent political movements that were considered launching pads of our war of liberation.

In 1971, when Dr Islam was in the UK, doing his doctoral studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, he helped raise funds for the war and mould world opinion in our favour. He collected newspaper clippings of the coverage of the war by the frontline newspapers of the UK in 1971 which eventually became a small archive. He later gave the archive to Bangladesh National Museum of which he was a trustee board member and chair for some time. After his return from the UK, he began perhaps his most fruitful career as a teacher and a scholar who wrote and spoke on literary, cultural and political issues untiringly until his death. I was amazed to see a post-editorial written by him in daily Jugantor only a few weeks ago. I was told that he wrote a page of a post-editorial even on the day he was taken to the hospital. I was not surprised. This dedication to the task in hand is what made him so admired and trusted.

Dr Islam taught in Karachi University (where he helped establish the Bangla department), worked as a journalist in daily Sangbad, served Bangla Academy and Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy as director (that was the post of the chief executive of both the organisations then). As I am writing from memory without the help of a detailed CV of his, I might be missing a few of his public engagements, but making a list of institutions which he served or the books he wrote or the prizes he received (he was awarded both the top honours of the country—the Ekushey and the Swadhinata Padaks) is redundant considering how as a person of vision, foresight and integrity, he stood taller than all his achievements. He was a good friend to his peers, a trusted mentor to his students and a sought-after companion for all those who ever knew him. He was a loving family man and was proud of his children. He spoke with love and respect about his wife who left him a few years ago. He was sharply critical of those who distorted the history of our liberation war and those who fanned communalism in the country. But I never saw any malice in his voice. It was the principle that mattered to him, not individuals.

It's a commonplace to say about a dearly departed that the vacuum left by him or her would never be filled up. Looking back at the illustrious life of Dr Mustafa Nur-Ul Islam, I see how some common expressions still have their weight; I too believe that his absence will be forever felt. The examples of dedication and duty, of compassion and understanding, of active engagement in issues that directly affect us will inspire those who knew him to follow him and set their own standards of excellence.

Syed Manzoorul Islam, a retired professor of Dhaka University, currently teaches at ULAB and is a member of the board of trustees of Transparency International Bangladesh.

Comments