Values that will endure

It makes perfect sense why ancestor worship flourished in ancient societies. It also stands to reason that upholders of dominant faiths have tried to keep this trend in check by limiting periods of mourning and remembrance and discouraging the practice of offering libation at the shrines of saints, Sufis and pirs. Those who have left us inhabit other spaces of which we know nothing. Only occasionally we make connections through dreams, visions and the intricate tricks of memory and remembering. In exploring these relationships, we try to make sense of the lives they lived, the choices they made, the impact they had on others and learn from these. We find inspiration and meaning and above all guidance.

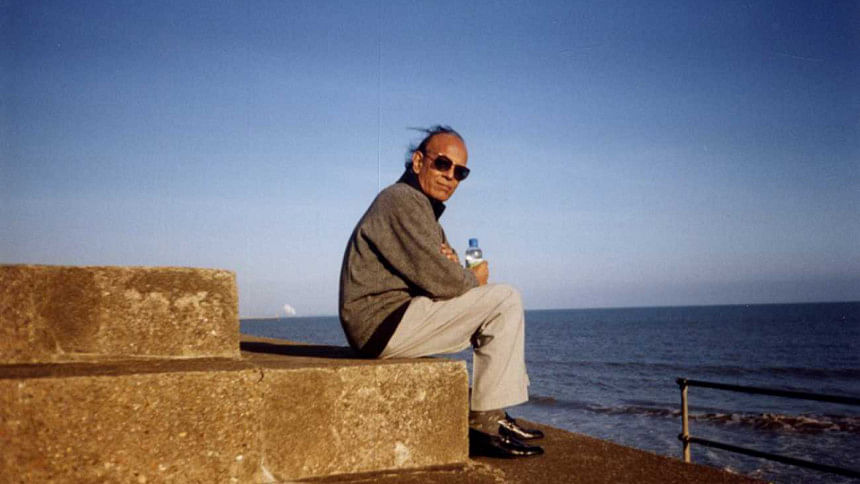

My parents, so far and yet so near - I look for them around me, in their friends, in relatives and in me. We all carry bits of them with us. And I try to reconstruct an ideology, a way of life, a way of thinking, a way of being. The objects that would help such reconstruction are not easily accessible or available anymore. But I would like to tell their story around some of the artefacts that were around them. Each of these brings out certain aspects of their character, their response to ideas. One such object is the 'Venus Bust'.

It was in the summer of 1964 that my elder brother, Firdous, and I accompanied our father, Sarwar, back to Dhaka after a two-year stay in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the USA. On our way, we stopped in London and Athens. It was in Athens that he bought the white marble bust of the goddess Venus. This was a symbol of perfection and beauty. He hand-carried it all the way home and gave it pride of place in our living room. My mejho khala, Nadira, was shocked: 'Dress it up quickly!' she ordered. But that was not to be. No one else objected, neither my paternal grandfather, Wakil Ali Ahmed Khan, nor my maternal grandmother, Bibi Khatimunnissa.

Having been permitted to jump a class or two in the US, I had just completed grade 7 and my brother, grade 9. Abba had been on a Rockefeller Fellowship at Harvard from 1961. We joined him a year later, amidst great excitement about going to a foreign country for the first time in our young lives!

I remember how carefully we had to plan what to take, because of the weight limit. We each had a British Airways in-flight carry-on bag that made us feel very important. September was not yet too cold. So, winter clothes would be bought on arrival. Yet, our mother worried that we might be cold on the way! The girls wore pretty nagra shoes that drew a lot of attention in Rome, and cream-coloured dresses that our mother had hand-made. She used to sew our clothes in those days. Legend has it that she made the Eid clothes for her children, nephews and nieces, and once she started sewing, she would not stop until she had finished. And all the while her mother-in-law would keep her nourished by sending her food to her sewing table! Dressing us for school in the new country was carefully budgeted. Clothes were tastefully selected, replete with winter coats, mufflers, hats and shoes, so that we always looked smart and did not appear to want for anything.

Settling down in Cambridge, Mass. was fun for the children. School was playful. No homework. We had study periods in school for quiet self-study, and plenty of extramural activities. Initially, we all enrolled in our neighbourhood school called Henry Wadsworth Longfellow School. Within days, I was bored, and refused to go to school. I would finish my tasks within a few minutes, and then found it hard to sit still for the rest of the period. It must have been similar for Firdous, for Abba soon found Buckingham School for me and Brown and Nicholls for my brother.

For our mother, Noor, it must have been challenging. Cooking and cleaning for a family of six, children always hungry, and the demands of her own studies for a Masters in Politics at Boston University, while working at Harvard University library after hours to augment the family income. But she never complained. In fact, she embraced the opportunity to teach herself to type so that she could submit her essays in type. Several of her essays were later published in the journal New Values, of which Sarwar was the erudite editor.

By the time the two academic years were over, we were no longer homesick. We all had strong American accents and good American friends and felt ourselves American pledging our loyalty to the US flag. We joined in all the activities in school including ballroom dancing, art, swimming, singing Christmas carols, etc., so that we could be a part of the class. We were thus never treated as different, and nor did we feel different.

Dhaka society was quite conservative in those days. Sending your children to co-ed dancing classes was not a light decision. Our parents had to negotiate these choices with each other in the best interest of their children in a foreign country where the norms were different. Noor managed to convince Sarwar that the children should enjoy all the educational facets on offer, and participate fully alongside all the other children in class, otherwise they should send the children back to Dhaka!

Concern with our education had been a key driving force for our parents. We were introduced to American music: Joan Baez, Burl Ives, and Kingston Trio. What we watched on TV was steered carefully. We watched the Shakespeare series 'Age of Kings' as a family activity, and looked forward to it with great enthusiasm. The series told the stories of British kings through the tales of Shakespeare.

Nevertheless, Abba was worried that we would lose our language and culture. Therefore, he obtained books in Bangla up to grade 10 and we had to study Bangla with him every day after school. As a result, we remembered how to read and write in Bangla. It was a bit easier for the older two than for the younger two. Despite this, upon return to Dhaka, it was quite a struggle to keep up our grades in Bangla. An excellent tutor was thus hired to assist us with Bangla and mathematics. Notably, the levels of math in our prestigious Cambridge schools were not the same as in Dhaka.

Though encouraged to stay on in the US by his peers, Sarwar along with Noor decided to return to Dhaka. Warnings of approaching doomsday in the form of a possible break-up of Pakistan, sounded by Henry Kissinger, a senior Fellow at Harvard University, did not deter them. News had come through that Field Marshal Muhammad Ayub Khan had stopped the arrest and detention of political figures in East Bengal, and that women were not his targets. Our mother, who had been a minister in the United Front government on an Awami League ticket in 1954, could thus safely return home. And so, they did go back to the lands of their parents, aspiring for their children to grow up as proud, well-bred Bengalis, attuned to their culture and heritage, with a silent expectation that one day they would in turn contribute to the betterment of their country of birth.

The values they cherished, the appreciation of order, truth, beauty, empathy, embracing difference, nobility in spirit, and kindness in manners; to dream of just and beautiful but orderly societies; to desire a culturally rich and plural Bangladesh where honesty and integrity are its cornerstones – were no mere wishful thinking, but their lived experience. These values will hopefully endure now and through the next generations in the years to come.

Tazeen M Murshid is a historian with a D.Phil. from the University of Oxford.

Email: [email protected]

Comments