Economic pitfalls: Can South Asia turn itself around in 2023?

The year of 2022 was supposed to have been one that helped nations accelerate their recovery from Covid-induced economic shocks. Asia was all set on the path of expedited economic growth, with World Bank (WB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) growth projections looking favourable.

According to WB's "South Asia Economic Focus, Fall 2021," published in the ending quarter of last year, Bangladesh's growth rate was expected to reach 6.4 percent in FY 2021-22. Similarly, India was expected to grow at 8.3 percent. Riding on the back of rebounding tourism, Maldives' prospects looked bright at 22 percent. And although stuck in the range of three percent, the growth potential of Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan seemed positive.

But for the South Asian region, these opportunities soon turned into behemoth challenges.

A hike in energy prices in the global market – mostly driven by the uncertainties resulting from a war unfolding in Europe – made our economic journey into 2022 perilous and riddled with pitfalls. As usual, the commodity price hike had a trickle-down effect on the overall economic parameters of countries across the world, and South Asia also found itself in uncharted waters. Inflation soon unleashed its impact on people's costs of living and purchasing power, resulting in nations revisiting and reworking their economic and monetary policies and their overall outlook for 2022.

Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, and Maldives all suffered. But the fate of Sri Lanka was perhaps the most unfortunate and climactic.

Sri Lanka, due to an already crumbling system – riddled with corruption, nepotism, and incompetence resulting from years of unchecked dynastic political misadventures – simply gave up. Unable to pay the huge amounts of external debt, the country declared bankruptcy, as its economy teetered on the brink of collapse. There was a shortage of food, halted sale of fuel, and no papers for students to write on during exams. Sri Lankans were out in the streets demanding the dismantling of the government – a point they drove home in only a few weeks.

People in Pakistan, too, took to the streets in the face of rising inflation. As food and fuel prices shot up. Pakistan's inflation reportedly reached a staggering 13.8 percent in May 2022. Protests broke out across the country, calling on the government to rein in the prices. As the country's inflation rate shot up to 27.3 percent in August, the highest since May 1975, the IMF warned of further protests. The country's inflation rate of 23.8 percent (as of November 2022) is still a pain point for the people and the government.

Bangladesh and India, while not in such a dire strait, are facing their own problems in pushing down prices within the purchasing power of their respective populations. In both countries, the urban poor and the lower-middle and middle income groups have been hit hard by the ongoing global crisis.

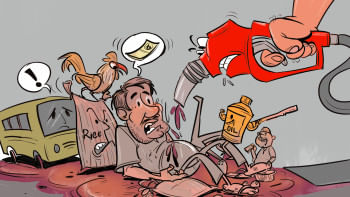

A price comparison study by The Business Standard, based on price lists of essentials from November 4, 2021 and from August 14, 2022 of the Trading Corporation of Bangladesh (TCB), revealed the grim reality of the Bangladeshi people. Between the two dates, the price of coarse rice increased by 14 percent, lentils by 23 percent, bulk soybean oil by 19 percent, eggs by 45 percent, broiler chicken by 18 percent, atta by 38 percent, and potatoes by 20 percent.

The report further added that transportation fare has increased by up to 55 percent post the double hike of fuel prices.

And this has adversely impacted people's disposable income and their ability to save money. A report by The Daily Star suggested that deposit growth rate has slumped to just eight percent in the July-September quarter of this year – a five-year low. Unable to make ends meet, the urban poor and those in the lower-income bracket are having to skip at least one meal a day.

The situation is also similar in India, where inflation is keeping food and fuel out of the reach of lower-income and middle-income people, turning dietary essentials such as milk into luxuries. It has been reported in The Swaddle magazine that 32 percent of households are having a tough time meeting their monthly expenses, including rent and mortgages. And companies producing entry-level consumer goods have also witnessed a decline in sales.

In Nepal, the rising prices has resulted in a unique problem: more and more people are now falling victim to cholera, as they are not able to boil drinking water due to the increased price of energy and its supply scarcity, and also because they are not able to afford bottled water.

Maldives is still counting on increasing tourism to cope with the economic shocks of the Covid pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war.

According to the WB's "South Asia Economic Focus, Fall 2022" report, the region's growth is expected to slow down to a 5.8 percent average – a two percent drop from the projection of 7.1 percent stated in the aforementioned 2021 report.

The way ahead for South Asian economic recovery is clearly fraught with perils and, if anything, at this rate and with no end in sight to the European conflict, things might only get more difficult for the people and for policymakers.

It is high time the countries of this region looked towards finding localised solutions to support each other and navigate these challenges through strategic bilateral and multilateral initiatives, especially in trade. All of these countries have very strong geopolitical and socioeconomic unique selling points (USPs) which they should revisit and assess how best they could utilise to cushion the South Asian region from prevailing economic pitfalls.

We need to open up to possibilities available outside the ones offered by the West. These are uncertain times, and would require unique solutions. For this, South Asian countries need to rise above seeking short-term internal gains and look at the bigger picture of achieving a strong regional growth trajectory and the benefits this will bring about for every player. With national elections on the horizon for many of these countries, this could pose a challenge of its own. The question remains: do we have the appetite and the desire for it? Only time will tell.

Tasneem Tayeb is a columnist for The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is @tasneem_tayeb

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments