Isn't it time we stop shooting the messenger?

Recently, a video of two television journalists being attacked by staff of a popular private hospital in Dhaka has been doing the rounds of social media. The reporters were covering an allegation of sexual harassment against a female patient by a staff of the hospital, and were apparently interviewing someone in the management when a group of hospital employees stormed into the room, questioning the presence of the reporters in the hospital, forcefully demanding that the cameraman shut off his camera, before finally resorting to manhandling them. When they protested that they were journalists who were only doing their job and didn't have any intention to defame the hospital, one of the employees thundered, "Faizlami paisen? Kisher journalist?" [Are you kidding? What journalist?] Reporter Ahmed Saleheen and cameraman Shafiqul Islam, both from Shomoy TV, further claimed that they were verbally abused by the hospital staff; in fact, Shafiqul was also confined in a room for a while where they allegedly beat him up.

When you find the hospital staff abusing journalists for trying to uncover the details behind an incredibly gross incident, it leaves you concerned, not only because it exemplifies the prevalent culture of shooting the messenger to hide the crime, but also because through their actions they prove that the reputation and image of their hospital is far more important than a patient's allegations of sexual harassment.

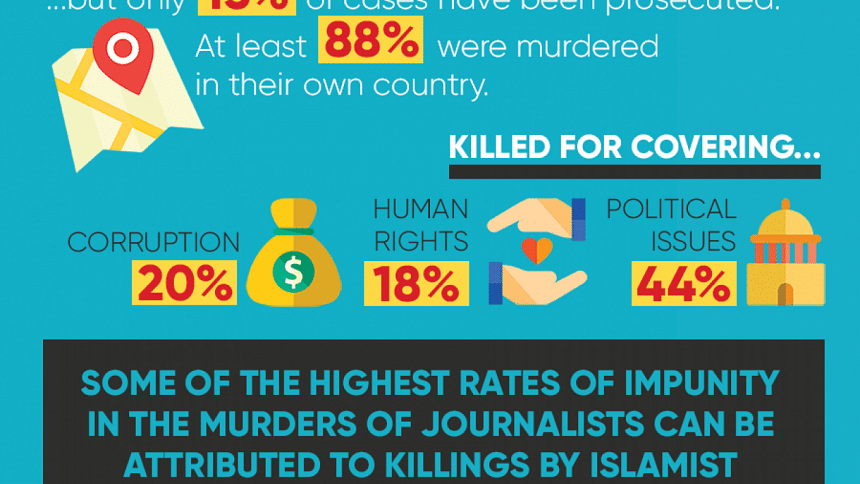

While the hospital management has promised exemplary punishment for their staff 'if' they were found complicit in the abuse of the journalists, it goes without saying that impunity for any kind of crime against journalists – be it verbal or physical abuse or even murder – has more or less been a mainstay in global culture for quite a while now. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) states that out of 110 journalists killed around the world in 2015, while many died in war zones, the majority were killed in countries supposedly at peace.

The rising numbers of crimes against journalists can be attributed to the neglect of state agencies around the world to bring the perpetrators to justice. In Bangladesh, placed 144th among 180 countries by RSF's World Press Freedom 2016 Index, crimes against journalists are seldom solved, emboldening perpetrators to continue attacking media workers with a strong sense of impunity. Lest you have forgotten, a journalist couple, Sagar Sarowar and Meherun Runi, were stabbed to death in their apartment in 2012. While the case received immense and intense media coverage and worldwide condemnation alongside a promise by then Home Minister Sahara Khatun, of apprehending the perpetrators within '48 hours', even after four years, the motive behind the murder remains unclear and the case remains unresolved.

The media watchdog group Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) recently posted a Global Impunity Index, listing 13 countries where the murder of journalists could be carried out with no consequence. The index included countries with more than five unsolved murders and measured how "judicial a country is in case of murders of journalists." Bangladesh placed 11th on the index - a slight improvement from last year - which calculated journalist murders from September 1, 2006 to August 31, 2016. The index showed that the murder of seven journalists remained unresolved and no convictions have been obtained in the country over the past decade. The RSF index also maintained that the government of Bangladesh "took little action in response to violence against media personnel and were sometimes directly involved in violations of their freedom."

Senior journalist and Editor of Bangla 71 Probir Sikder's case is testimony to this allegation of RSF. Sikder was arrested in 2015 when, after receiving death threats following articles he had written about a local property dispute, he posted a statement on Facebook alleging that a minister amongst others should be held responsible if he were to be killed or harmed in any way. He also claimed that he was compelled to post the statement after the police refused to take action over the death threats. Sikder further asserted that the police did not record his general diary but arrested him even before the case was filed (The Daily Star, August 20, 2015) While the said minister denied pressing the charges against the journalist in local media, he also claimed that Sikder should be put "behind bars" for writing against him. The charges against Sikder were framed under Section 57 of the ICT Act, which states that anyone convicted of tarnishing the image of a person or the state through writings or electronic means can face a minimum of seven years and a maximum of 14 years in prison. Leaving aside discussions on the validity of the Act, which activists condemn as a threat to freedom of expression, the fact that a defamation suit can lead to the arrest of a person in a democracy is not only a travesty of justice but also contradictory to the Constitution that our state apparatuses want to uphold at any cost.

Defamation seems to have become the new go to phrase that allows people to lodge complaints and demand the arrest of any person who is deemed to have hurt the sentiments of any individual, especially of those in power. In a case that received global attention, 83 defamation cases were filed against the editor of this newspaper, all of which were subsequently stayed by the country's High Court.

Concerted attacks against media are not uncommon in Bangladesh. Reporters and photojournalists have often been attacked by political party activists at different points when they tried to cover an election, by student politicians when they attempted to report violence in education institutes, by doctors when they sought explanation for a strike called by them. In short, they are the easy targets because they take the news to the public, making the invisible visible, and talking about the unspeakable. In 2015, ten journalists were assaulted by ruling party men during the city corporation elections; some reporters were even robbed of their mobile phones, handbags and cash. Allegedly, polling officers and law enforcers prevented reporters and photographers from entering the polling centres. When a reporter of The Daily Star exited a booth where he snapped pictures of a polling agent illegally stuffing ballot boxes in the presence of an assistant presiding officer, he was asked by a man in plainclothes identifying himself as a policeman to delete the photos and leave the place (The Daily Star, April 29, 2015).

Interesting to note that when defamation (or any other) charges are brought against journalists, it doesn't take much time for the law enforcing agencies to bring them to book. Under the guise of sedition, defamation, and making statements that are offensive to such and such groups, journalists are repeatedly harassed and diligently scrutinised. The same diligence, unfortunately, does not seem to apply for the members of the journalist community when they are attacked. As stated by CPJ, in the last ten years the only notable progress in Bangladesh in terms of conviction of crimes against journalists was the court order that convicted eight people for the murder of blogger Ahmed Rajib Haider in 2013.

The fault also lies on the journalist community of the country which stands divided, unwilling to let go of individual self-interest in favour of a freer, more open and critical news media. Self-censorship is so prevalent in our community that the fear of 'conflict of interest' often overpowers our need to present facts without bias or favour. This polarisation is probably a main reason why as a community we have failed, and miserably so, to ensure justice for our brethren who were forced give up their lives in the line of duty or are continuously harassed by different agencies for attempting to do their job.

The situation of few convictions of crimes against journalists has become so endemic that we now have a day that calls to end impunity for such crimes! What the world in general needs to understand is that it is only through the implementation of a free and fearless news media that we can achieve the peace that we so desperately seek in these turbulent times.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments