‘When people with integrity begin to rise, corruption fails’

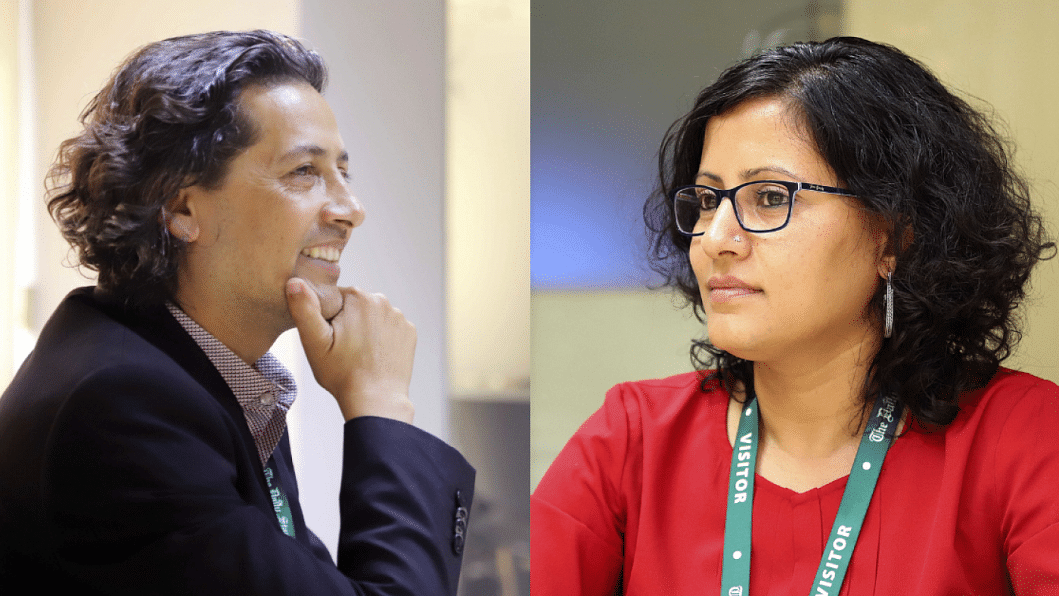

Narayan Adhikari is Nepal country director and co-founder and Sanjeeta Pant is programmes and learning manager at Accountability Lab. In a conversation with Eresh Omar Jamal of The Daily Star, they discuss the Accountability Lab's Integrity Icon initiative, which recognises and awards public servants (across 15 countries), nominated by citizens and others for demonstrating exceptional integrity at work and their personal lives. It is an attempt to address the perception of widespread corruption among civil servants in these countries, and encourage greater integrity in the profession.

What motivated you to create Accountability Lab and the Integrity Icon initiative?

Narayan Adhikari (NA): When we started Accountability Lab, we wanted to do something positive, inspiring, innovative and creative, especially when we talk about working around promoting good governance. When I was working in various youth campaigns, we did a lot of anti-corruption events. But the results were not satisfactory, because if you keep pointing fingers at others, they will do the same. You are not creating an environment of trust, to co-create something that is more valuable to society. That is when we came up with the idea of Integrity Icon.

Integrity Icon aims to build an ecosystem of accountability and integrity in governance, through promoting individuals within the public service – identifying them, using their innovative ways, using the power of their personal honesty and integrity as a role model to inspire more public servants, citizens and the younger generation. Then we can really have a governance system that would work for the people – one that is inclusive, efficient, effective, and pro-citizen.

What positive results have you seen from the Integrity Icon initiative?

Sanjeeta Pant (SP): One positive result is how the icons themselves have been able to grow within their organisations or departments. When you talk about anti-corruption in governance, it is a pretty big issue. There are very interesting stories that have come out from all over the place, of how these icons have been promoted within their organisations because of this recognition, or given certain responsibilities that relate to the transparency and accountability of their organisations, because they are seen as "Integrity Icons."

The general perception of most people about civil service in a lot of South Asian and African countries, where we predominantly work, is that the government is inefficient and corrupt. A lot of people don't want to get into civil service. We want to change that perception, so we identify young people who want to go and work with these icons to see for themselves – and oftentimes they come back feeling inspired. Because what we don't recognise is that sometimes the civil servants are working in very difficult circumstances, with limited resources. A lot of people feel like that is how they can justify being corrupt. But there are people who are still showing up for their jobs, who actually sacrifice a lot to perform their duties with integrity. Our job is to create that ecosystem – and also changing norms and behaviours around what civil service needs to look like.

What were some of the initial challenges that you saw?

NA: Many people were sceptical about the idea. Of course, we need scepticism – it is good for a healthy conversation. But even governments asked questions like, "Do you think you are going to find anyone with integrity?" First, people doubted whether we would find anyone with integrity; second, even if we did, they were not going to continue with their good behaviour. Third, the government would push back. And finally, it would not make any difference because the whole system is so corrupt and bad.

Our conviction was, of course, that the system is not working and is corrupt. But if you want to bring change, you have to disrupt the system. And the Integrity Icon project is disrupting the process of how we fight corruption in governance, to some extent.

How has your initiative motivated people who are in public service?

NA: For many people, getting a government job might be the last resort. But for some people, it's always the first choice. But why do they want to get a government job? Because it's a nice job, they get a lot of opportunities within the government, such as getting education scholarships. And in the end, they get a good pension. So, peoples' motivation for getting into the government is not really about making a difference and fulfilling their duties honestly. After they retire, they may own a big house, make lots of money, but oftentimes, they are not really satisfied and they are restless because, internally, they know they have done nothing other than amassing more wealth.

What we are saying is, imagine: after you retire, how would you like to be remembered? Would you like to think, "Amazing, I have five houses and cars and I am sending my kids to foreign universities"? Or would you like to be remembered as a person with integrity?

Compared to other jobs, the salary and benefits of government jobs are also not bad. It's just a matter of how you manage your personal life. Some people say they have a low salary, and that is why they are corrupt. But our Integrity Icons go and explain to them: "Look, if you do your jobs with honesty, with the benefits and facilities you get from the government job, in five years, you will buy a small car with white money. In maybe 8-10 years' time, you can buy a house because you can get a soft loan from the government, and you will also have money to pay the school fees of your children. This is how I have done it, without corruption."

If you can do all that, what else do you need? Unless you make bad personal choices, you don't have to do any corrupt activities. Having integrity is not just about how you do your job; it's also about how you manage your personal life.

You have now expanded the Integrity Icon initiative to 15 countries. How is that working from country to country?

NA: We basically share our experience and process, but we are also very open to incorporating the local context. Public service system is different everywhere and the context is not the same either. So, the basic idea is to find the right individuals that are honest and inspiring, highlighting them, engaging them, and to really try and make our governance system transparent and effective.

SP: And sometimes you just need one or two individuals. We have seen that in many cases, including with the Nepali electricity authority, where we had a load-shedding problem for almost two decades because of lots of corruption and mismanagement. Then we saw just one person coming in, and he changed it almost overnight. That goes to show that sometimes if you have the right person doing the right thing, they can really change the tide.

Do you think this initiative will be a good fit here in Bangladesh?

NA: I would really like to see the Integrity Icon in Bangladesh. It's not really about "naming and shaming," it's really about "naming and faming." And I see there is a lot of potential in Bangladesh, with a lot of young people and a vibrant civil society and media. Bangladesh is a special country with a long and diverse history of bureaucracy. And it also has many challenges. To some extent, this initiative could help to overcome them; because when people with integrity begin to rise, corruption fails.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments