Daniel Kahneman and his influence on our policymaking

One of my favourite economists, Daniel Kahneman passed away a few weeks ago, on March 27. He won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 even though he had never taught economics or taken an economics course. Known as the "grandfather of behavioural economics" and listed as one of the seven most influential economists in the world by the Economist in 2015, he was a professor in both psychology and public affairs since 1993 at Princeton University. Kahneman died in New York.

Kahneman influenced generations of economists by upending the basic tenet of economics. Adam Smith proposed that a "consumer" is a rational decision-maker. Kahneman and his fellow researcher Amos Tversky discovered "anomalies" in human behaviour. In pioneering experiments, the duo validated many departures from our pristine "rationality" model, including status quo bias, endowment effect, scope sensitivity, and loss aversion.

Let us take an example. If you lower the price of a good or offer a discount, people buy more of it. "Not so simple", they said. Their experiments demonstrated various cognitive biases. They showed, for instance, that many more people were willing to make a 20-minute trip to save Tk 20 on the price of a Tk 120 train ticket than to make the same trip to save Tk 20 on a Tk 300 train ticket—an example of what is known as the framing effect.

The recent bout of inflation and RMG wage negotiations that followed are also illustrations of how behavioural economists have validated an old concept known as the "Money Illusion." Economists Eldar Shafir and Peter Diamond and psychologist Tversky found that in periods of high inflation, employers can get away with giving workers raises that amount to substantial wage cuts on an inflation-adjusted basis.

Suppose inflation rises at a 10 percent annual rate, and you get a five percent raise. You've just received a real wage cut. If there's no inflation, and your wage is cut by three percent, you've also gotten a wage cut—but you've lost less money than in the case of high inflation. What's odd is that workers tend to view the bigger real wage cuts as fairer.

I recently wrote on the worrisome situation in higher education with new graduates facing very limited job opportunities in the country. Obviously, the next question to ask is, can we not steer the job-seekers to the jobs that are available? Or, have them take a crash course in skills they did not acquire during their college days—"soft skills", technology skills, or even language courses? The answers to these questions are not clear-cut. Kahneman and others confirmed experimentally that new graduates often have to overcome their risk aversion and status quo bias. More on that later.

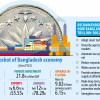

I will pause for a second and acknowledge all the skills training programmes that the government has initiated in the last 15 years. We borrowed hundreds of millions of dollars from foreign multilateral development banks and government agencies for skills training, some for vocational and technical skills, and others for so-called manpower development. The EDGE project aims to train 80,000 students in three phases. Of them, 50,000 will get training on fundamental issues at the foundational level, 20,000 on more complex issues at the intermediate level, and 10,000 on frontier technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, robotics and blockchain at the advanced level.

But the project is off to a very slow start. While AI and blockchain are very much state-of-the-art technologies, employers in Bangladesh are also voicing their concern about the absence of other soft skills, including communication, teamwork, and adaptability. A Center for Policy Dialogue (CPD) online skills assessment survey of graduates showed that the highest average score was obtained for "creativity", whereas the lowest average scores were recorded in "Communication, English language skill, Numeracy, and Mathematics."

One cannot deny that economic policymaking for a developing country like Bangladesh can be very tricky. Sometimes a political shift, or just a change of heart among bureaucrats at other times, can overturn the cart. Just look at our environmental policies.

Status quo bias is the phenomenon (backed up by some significant evidence) that humans have an objectively non-rational preference for the status quo. A 2009 paper published by the US National Academy of Sciences found that when faced with difficult choices, people are more likely to choose the status quo. In addition, the study also noted that these choices were frequently not the "best ones" but that the difficulty of making the decision was a factor in driving people to stick with the familiar.

Like economists, agricultural scientists have often been baffled by the flawed choices people sometimes make. For them, the question is: "Why isn't there a faster adoption of agricultural innovation that has obvious benefits?"

Richard Thaler, another behavioural economist who followed Kahneman's path, provides a clue. In his 2017 Nobel speech, he said, "We humans are absent-minded, a bit overweight, we procrastinate about saving for retirement, and—crucially—we are influenced by many supposedly irrelevant factors: how questions are phrased, what happened yesterday, what's the default."

Another example is the slow progress towards diversifying our manufacturing non-RMG sectors. Is it simply because of status quo bias or lack of policy support? That's a discussion topic for another day.

As Kahneman might have said, "policymaking is not for the faint-hearted".

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and works for Change Healthcare, Inc., an information technology company. He also serves as senior research fellow at the US-based International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments