The Fed faces an uphill task

Central banks across the globe have a few lessons to absorb from the recent US experience. Inflation reduction with interest rate hikes can be likened to a Sisyphean task since it is a very laborious process and seems almost impossible to complete in haste. The Fed embarked on this path more than a year ago, in March 2022, with the first increase since December 2018. So far, it has raised the bank rate nine times, and while there is some discussion of a halt, it may be too early to predict if the war on inflation is over.

For the Fed, this should have been a good time. Inflation has slowed down, the GDP growth rate, while modest, still has been steady, and the most important thing is nobody is talking any longer about recession, except for a few on Wall Street. World's major economies have averted significant job losses. So, one could say that central bankers around the world could heave a sigh of relief and let inflation come down to the targeted two percent rate. But, any cursory glance over the financial news from the US, Canada, and the EU would indicate that the markets are still turbulent.

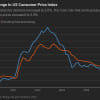

First, does the data show that the Fed's job is done? Yes and no, and the answer depends the metrics used. The Fed's two percent inflation target is still looming large on the horizon. US inflation rate is at 4.98 percent, compared to 6.04 percent last month and 8.54 percent last year. This is higher than the long-term average of 3.28 percent. According to some predictions, inflation will come down to this level in 2024.

Second, the trade-off between a rate hike and a lower GDP growth rate is increasingly becoming fragile. Conventional wisdom dictates that lower inflation moves in tandem with GDP slowdown. That is not a certainty any more. It is openly accepted that efforts to reduce inflation rate could end in a soft landing, a bumpy one, or a crash, meaning a full-fledged recession. Forecasting models have since last year revised the probability of a recession, but all these have been off the mark. The unemployment rate dropped to 3.4 percent, the lowest in 54 years.

We also saw that all forecasts about future GDP growth are couched in terms of various degrees of uncertainty. The Conference Board said in March 2022 the probability of a recession, which was zero earlier, jumped to over 30 percent in April and reached 50 percent in May. That means that the US economy should have been in recession during 2022-23, but it hasn't! The probability rose further and has remained elevated but the forecasts are all fuzzy. What is the latest probability? We can only say that the "banking crisis dramatically increases the odds for 'hard landing' recession," as one observer put it.

One of the drivers of the current crisis is the fear of the depositors whether their money is safer in their local bank or in a larger bank.

Third, the lessons for the central banks from the Fed's experimentation are profound. Bangladesh has two problems similar to the US – a relaxed regulatory framework and a banking sector with questionable accounting practices. In the US, the rate hikes proved hazardous for the commercial banks, as evidenced by several regional bank failures. Congress in 2018 relaxed banking regulations which allowed smaller banks to make their own plans and escape scrutiny from the Fed's banking regulators. If anything, it is evident that small and large banks need a more robust regulatory watchdog. Small or medium size banks like Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank managed to fly under the radar and then got into serious trouble. The fallout can be contagious and lead to bank runs.

One of the drivers of the current crisis is the fear of the depositors whether their money is safer in their local bank or in a larger bank. A recent survey shows that 48 percent of US adults are concerned about their deposits.

Fourth, there are many other unintended consequences of a rate hike. Bank balance sheets suffer, small and medium-sized enterprises find their cost of borrowing increase and go belly-up, and the credit crunch hurts the smaller borrowers disproportionately.

Fifth, to contain the bank strains, appropriate "macroprudential policy", or rules that aim to mitigate risk to the overall financial system, need to be carefully tailored. The Fed teamed up with the Treasury to create the Bank Term Funding Program, a new backstop facility designed to make additional funding available to banks in the event of a deposit flight, and this proved to be effective.

On the social effect, the Fed's rate hikes have adversely affected the poor people more and are always at the receiving end. As we saw, inflation hurts the poor (because the price of basic needs increases faster), but the fallout from rate hikes hurts them, too (due to job losses). From January to March, average monthly job growth dropped to 222,000 from 524,000 a year ago. Initial claims for unemployment increased and unfulfilled job openings dropped.

Another lesson for policymakers is, sometimes the window of opportunity to curb inflation is narrow. Last year, for example, the Fed waited too long in the mistaken belief that the inflationary pressures were transitory – another example closer to home. Bangladesh Bank, banking regulators, and the government ministries wait too long before taking action on bad actors. One can only caution them to be vigilant, practice due diligence, and enhance quarterly review and monitoring. Currently, the oversight is too weak, and reliance on a public-sector bailout to prop up failing banks creates a "moral hazard".

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and works for Change Healthcare, Inc., an information technology company. He also serves as senior research fellow at the US-based International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments