In search of a happier Bangladesh

Once, the Greek conqueror Alexander the Great met the great philosopher Diogenes and asked if he could do anything for the sage. Diogenes didn't ask anything of the king; rather he tartly told the commander not to block the sunlight which the philosopher was basking in. The hermit conveyed to the ruler that he shouldn't take away anything from the public which he can't deliver to his citizens.

Enjoying basic natural rights is the first principle of happiness, and that instantly justifies why Afghanistan turned out to be the unhappiest nation on the planet. It also tells us why Finland, Denmark, and Iceland – the three most reputed welfare states – occupied the first three places in the happiness index devised by a pool of experts under the guidelines of the United Nations.

The World Happiness Report 2023 has placed Bangladesh in the 118th position out of 137 countries. Surprisingly, Bangladesh's ranking was 94 in last year's report and has been downgraded by as many as 24 places, sparking both curiosity and concern as to why it happened. Some critics are labelling it as the government's failure, while some others are trashing the report outright as "a Western plot to malign Bangladesh."

Some discard it by arguing that happiness is a personal aspect and it can't be measured as a social indicator. That's not true. The price behaviour, which is measured at the individual level in microeconomics, can also be quantified at the state level in macroeconomics. We measure social psychology while it is initially studied at the individual level.

That is why the UN panel of experts has outlined six criteria to measure happiness at the national level: 1) per capita income; 2) social support; 3) healthy life expectancy; 4) freedom to make life choices; 5) generosity; and 6) corruption. Hence, the yardstick is the combination of both quantitative and qualitative aspects. For example, income and health indicators can be expressed in numbers, while elements like freedom, social connectedness, generosity, and corruption are perception-based, leaving some room for argument. But the UN social scientists have explained the methodology of how they handled each of the qualitative factors. Yet, blaming the ranking as an act of conspiracy against any nation won't convince the audience by any chance.

Highly corrupt nations are highly unhappy, a conclusion we can make by comparing the World Happiness Report 2023 and the Corruption Perception Index 2022, where Pakistan ranked 140th and Bangladesh 147th.

Of course, some rankings may seem anomalous to some readers. Seeing Pakistan (108th) ahead of Bangladesh (118th) in the World Happiness Report at a time when Pakistan is grappling with an acute reserve shortage as well as food and fuel crises may seem odd to many. But these recent phenomena are likely to be reflected in the next report. In last year's report, Pakistan ranked much below at 121st, while Bangladesh's position was 94th, creating no doubt to any critics or sceptics. This year's positions for these two countries are not statistically too different. Any position beyond 100 requires the respective governments to address why social happiness scores are so poor. And the single most dominant factor is the level of corruption.

Highly corrupt nations are highly unhappy, a conclusion we can make by comparing the World Happiness Report 2023 and the Corruption Perception Index 2022, where Pakistan ranked 140th and Bangladesh 147th. The happiest countries like Denmark, Finland, and Iceland have the least amount of corruption as they rank 1st, 2nd, and 14th in the Corruption Perception Index. So, it would be a wake-up call for the government to crusade against those public officials involved in rent-seeking tasks, lawmakers engaged in bribes, police members involved in unethical practices, businessmen turned wilful defaulters, high-scale money launderers, and political pollutants. The outgoing president acknowledged corruption as the main obstacle to progress.

The government is engaged in development projects one after another. But the positive sentiment is outweighed when people can sense the presence of massive corruption in most public works. People feel unhappy when they see that no big-scale money launderers and wilful defaulters have even been touched at all. The criminals who victimise children, girls, women or minorities are sometimes arrested, but rarely followed up with exemplary punishments. The drivers with fake permits and unfit vehicles keep on committing murders on the streets and highways, but are rarely caught or sent behind bars.

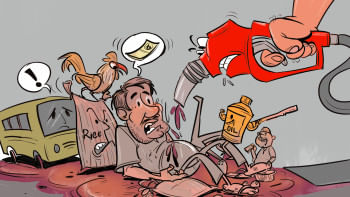

The spectacle of the tardiest possible judiciary, the drought of law enforcement, and the culture of massive impunity for the powerful make the helpless majority frustrated, demoralised, and disdainful. In this situation, the enthusiastic claim of a spike in per capita income by the finance ministry can't make the ordinary people cheer at this creditworthy message. That's why economic achievements on the one hand and the ever-growing financial turpitude on the other hand can't make people smile unconditionally. If a UN official approach them by asking, "Are you happy?" they say, "No." Corruption damages any gain in happiness, throwing the country into a lower rung of the ladder, and thus defaming the nation.

Some may argue that Bangladesh's position at 118th seems to be a mistake while Nepal's position in happiness is 78th, because Bangladesh is more prosperous than Nepal. Herein comes the question of rational expectations originally proposed in the early 1960s by the American economist John Muth. Given the differences in historical perspectives, geopolitical settings, and economic advancements between them, the level of expectations by Bangladeshi people are likely to be higher than that in Nepal, whose per capita income is less than half of Bangladesh's. Also, the low level of corruption in Nepal is a factor why it's happier than Bangladesh.

The Bangladesh government has to devise ways to make the country advance on the ladder of happiness because it is the ultimate objective of any ruler serving the country. Bangabandhu embarked on his second revolution in search for a happier Bangladesh. Anyone believing in his ideals must be serious to research on how to make citizens happier. The unemployment rate is now higher than at any time in the past. Megacities like Dhaka and Chattogram are simply unliveable. They are surcharged with sound pollution, toxic air, uncouth landscape cluttered by political posters, and one of the highest levels of congestion in the world. When the residents of these cities are interviewed on happiness by surveyors, saying that "they are happy" would be a parody of truth and travesty of justice. Those in power can do a lot to address these issues towards the task of making a happier Bangladesh.

Dr Birupaksha Paul is a professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland in the US.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments