Iran-Saudi détente: Has a major shifting of the sands begun?

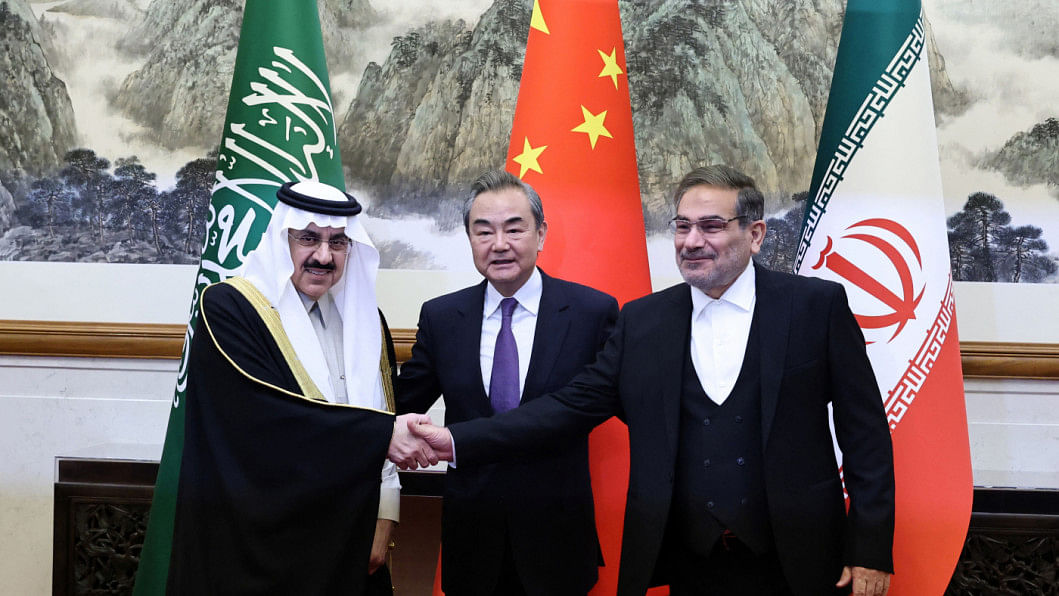

On March 10, Iran and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia announced a landmark deal – brokered by China in Beijing – to restore ties and reopen embassies seven years after severing relations with each other. In its most optimistic reading, the deal can be seen as a historic agreement, reflecting major changes happening in the region and in the world at large.

Sources familiar with the negotiations revealed to The Cradle that regional and domestic security and stability were the primary reasons for this deal, particularly for Saudi Arabia. And that was quite easy to spot, as the deal was struck between the Supreme National Security Council of Iran and Saudi Arabia, with the intelligence services from both countries in attendance. As such, confidential clauses were inserted in the agreement to assure that their security requirements would be met, including an understanding between the two countries that they would not engage in any activity that destabilised either of them at security, military, or media levels.

Saudi Arabia pledged not to fund media outlets that seek to destabilise Iran, such as Iran International. The Saudis also pledged not to fund organisations designated as terrorists by Iran, such as the People's Mojahedin Organization (MEK), Kurdish groups based in Iraq, or militants operating out of Pakistan. Iran pledged to ensure that its allied organisations would not violate Saudi territory from inside Iraq. There were discussions during negotiations about the targeting of Saudi Arabia's Aramco facilities in 2019, and Iran guaranteed that there would be no similar strikes from Iraqi territory.

Hostility between the two sectarian rivals – predominantly Shia Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia – has dominated Middle Eastern politics in recent years, spreading into Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen.

So, the final confidential clause includes the two sides agreeing to exert all possible efforts to resolve conflicts in the region, particularly the one raging in Yemen – although no details were agreed upon. And this, perhaps, is the most important part of the agreement, as it has the potential to bring some peace and stability to a region plagued by conflict and chaos.

The two countries that will clearly be unhappiest with the Saudi-Iran détente are the United States and Israel. According to The Guardian, the agreement has "potentially wide implications for the Iran nuclear deal" and "shows the new determination of Saudi Arabia to conduct a foreign policy independent of the west." To add to such concerns, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan Al-Saud recently said that he believed the Iran nuclear talks in their current form were moribund, and that it would be better to change the format so that other currently excluded regional powers were included in them. Additionally, the deal might also throw a wrench in the US-Israel plans to expand the so-called Abraham Accords introduced by former US President Donald Trump to include Saudi Arabia.

Why did China, which has historically always stayed away from mediating negotiations – partly not to lose any credibility should the negotiations or agreements not work out – put its neck on the line for this one?

China's role as the deal's mediator is another major red flag for the US, particularly because, according to inside sources, Chinese President Xi Jinping did not merely aid an agreement that was already going on between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The Chinese leader apparently personally paved the way for it to materialise, delving deep into the details of it since his visit to Saudi Arabia in December 2022, and then later during Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi's visit to Beijing last month.

And this is what is most interesting about the process of this agreement. Why did China, which has historically always stayed away from mediating negotiations – partly not to lose any credibility should the negotiations or agreements not work out – put its neck on the line for this one? Is it because it strongly believes that this agreement will be implemented properly? Is it because of its massive economic and energy interests in the oil-rich Middle East? Is it because China finally sees itself ready to exert its influence in a region predominantly considered as the United States' sphere of influence, particularly with the US authority dwindling after Russia took a stand against it in Syria, where Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, backed by Iran and Russia, is now clearly winning? Or is it a combination of all of the above, and then some?

Given the increasingly multipolar world and rising China-US tensions, the Iran-Saudi agreement illustrates how the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – especially Saudi Arabia, which earlier slashed oil production by two million barrels per day, despite a request by US President Joe Biden to increase output – are manoeuvring to balance multiple interests and partnerships. And there are legitimate geostrategic reasons for it.

After the 1973 war between Egypt and Israel, the then Egyptian President Muhammad Anwar Sadat unceremoniously dumped his Soviet military and political backers and started looking towards US President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to get the occupied Sinai back from Israel and to get Egypt out of the cycle of disastrous Arab-Israeli wars. While explaining why he was flying to Washington all of a sudden instead of heading towards Moscow, Sadat said the US "has 99 percent of the cards." What he meant was that it was the US alone which could conclude a peace between Cairo and Tel Aviv, as the Soviets did not have the same trust from the Israelis as the Americans did.

Fifty years later, it seems to be the Chinese who now hold most of the cards when it comes to relations across the Gulf region.

The extremely hard line taken by the US against Iran, with a de facto global financial and trade embargo against its oil exports, has meant that the US basically has no influence over Iran. Its unconditional support for Israel, invasion of Iraq, and support for armed groups against the Syrian government means that it has also alienated them.

With Saudi Arabia now pursuing a more independent foreign policy, this agreement with Iran, mediated by China, might signal a sea change in the global political order, originating, ironically, from the deserts of the Middle East.

Eresh Omar Jamal is assistant editor at The Daily Star. His Twitter handle is @EreshOmarJamal

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments