The price we pay with each deleted word

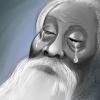

There are few things as draining—or as depressing, I imagine—as being the op-ed editor of a newspaper under constant scrutiny of an authoritarian regime.

Not least because I had to rewrite the first sentence three times to make it palatable for print. When you do that often enough—or rather, when self-censorship becomes your default setting—words eventually start to melt and evaporate into each other until they lose meaning altogether. And your life, built around those deleted sentences, becomes a burden from which you desperately want—but know not how—to escape. Every so often, I fool myself into believing that what we say after scraping off all that cannot be said will still serve some purpose, as if people will be moved to revolutionary actions by words that we do not have the courage to say out loud.

Whenever I ask someone to write, they tease me: can you publish what I say? I smile sheepishly. They smirk knowingly. Sometimes I retort: will you really say what you want to say, though? In fact, will you say anything at all?

It's incredible how little there is to say about the national election anymore despite the overwhelming urge to say and do something. Let's face it. We all seem to have grudgingly accepted our extended sentence under this regime. Whatever frustration and anger—but also excitement and anticipation—that could be felt in the beginning and middle of 2023 somehow turned into a disquieting resignation at the end of it. Even the ordinary people, whose anger reverberated through the streets earlier in the year, now just want to move on from the tragicomedy the election has been reduced to, and figure out what lies ahead with the inevitability of another term of Sheikh Hasina's government.

There can be little doubt that the space for dissent will shrink even further in the days to come, with the rebranded Digital Security Act (DSA)—now the Cyber Security Act (CSA)—yet to claim its first victim. During its five-year stint, the DSA has been strategically and systematically deployed to criminalise any sort of criticism of the government under vague provisions that can be arbitrarily (mis)used. The DSA's greatest success, if seen from the government's perspective, is not the cases against and subsequent harassment of thousands of dissenters, including 464 politicians and 442 journalists (the biggest victims of the DSA, as per the analysis of The Centre for Governance Studies), but the fear it has been able to generate among the common people about the imaginary lines one may not cross—lines that have been drawn and redrawn many times over the past 15 years of AL rule. We now know that one does not need any merit to persecute and prosecute people under the DSA—the sheer act of suing a person under it, the many irregularities in procedures and the denial of bail for months on end, if not years, are harassment enough for a lifetime. It's no surprise, then, that an overwhelming 72 percent of the youth feel too afraid to speak out and nearly half of those surveyed want to get out of the country the first chance they can get.

While we were all busy with the election preparations, the cabinet approved the draft Data Protection Act (DPA) in principle on November 27, without addressing any of the key concerns raised by various stakeholders since the bill was first introduced in 2022. The DPA will essentially legalise surveillance of the citizens' private data, allowing law enforcement agencies the right to "intercept, record or collect information" of any person on "national security" or "public order" grounds. Without any regulatory oversight over government agencies, we can well imagine how the DPA will be deployed in the days to come to keep track of our online and offline lives, and to "manage" dissent before it takes a dangerous turn.

There appears to be a lull in CSA arrests, likely because the state machinery is now preoccupied with harassing, arresting and sentencing opposition leaders and activists, many on "ghost" or trumped-up charges, since the infamous "khela" of October 28. Many RMG workers and labour leaders, targeted and arrested for their participation in the minimum wage protests, now languish in jail, denied bail for the past month(s). Meanwhile, with the legal harassment and subsequent sentencing of Dr Muhammad Yunus ahead of the election, the government seems to have sent a clear message to those it considers a threat: international condemnation be damned, the AL will do as it pleases.

As the ruling party looks to consolidate power for the fourth consecutive term, the question one would rather not ask is: who's next? Once the political opposition is silenced, the powers that be will likely redirect their attention to gagging free media (or what's left of it) and eventually the populace at large, whose frustrations with the cost-of-living crisis and rampant corruption are unlikely to simply disappear with the staging of the election. Dissent and disappointment in an authoritarian regime must be contained under any cost, and no one knows this better than the ruling party.

While we were all busy with the election preparations, the cabinet approved the draft Data Protection Act (DPA) in principle on November 27, without addressing any of the key concerns raised by various stakeholders since the bill was first introduced in 2022. The DPA will essentially legalise surveillance of the citizens' private data, allowing law enforcement agencies the right to "intercept, record or collect information" of any person on "national security" or "public order" grounds. Without any regulatory oversight over government agencies, we can well imagine how the DPA will be deployed in the days to come to keep track of our online and offline lives, and to "manage" dissent before it takes a dangerous turn.

The most depressing aspect in all of this is that we, the people, seem to have resigned to our fate. With each new term of the ruling regime, and each new provision or law, we have learnt a bit more of self-censorship; we have learnt to behave ourselves, to not cross the line no matter the temptation—in short, we have learnt to accommodate the powers that be and live by their rules.

But there's a price we pay for such subservience; every time I swallow a thought, delete a word, or tone down someone's anger, I kill a little bit of myself and all that I desire for myself and for the country I love. With every nail in the coffin of democracy, we lose who we were and who we had wanted to be when we fought for freedom in 1971.

Sushmita S Preetha is op-ed editor at The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments