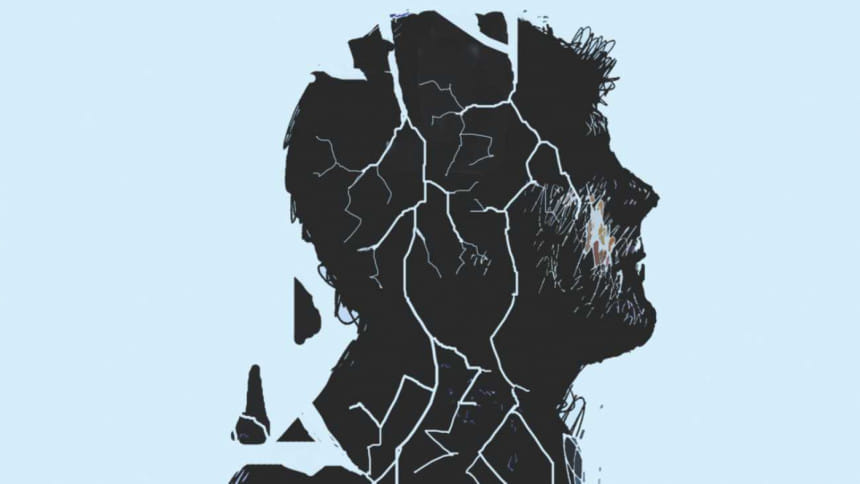

Suicide and irresponsible speech

In the aftermath of someone's suicide it is inevitable that those left behind will comment. The business of life is to do all we can to prevent death from being thrust upon us and those we hold dear. Self-preservation is a natural instinct. What could be more alien to our thinking than the idea of someone abandoning this instinct, and in fact being the instrument of their own demise? It is no wonder that cultures have historically seen suicide as an unusually significant cause of death—to be condemned or even required but never ignored.

This week two musicians have taken their lives, sending shockwaves throughout Bangladeshi social media. Chester Bennington was for many the voice that guided them through adolescence. Zeheen Ahmed was someone people knew and loved personally. Their untimely ends have produced a natural outpouring of love, remembrance and genuine grief. This is natural, it speaks for itself, and it is unnecessary to comment further. However, that they died through suicide has produced a range of specific reactions that would never have appeared for most other causes of death.

The first, and most benign, is the offer of help and support. Many of us know people who struggle with depression, feelings of inadequacy or self-loathing that we fear may lead them to consider suicide. Many of us have had suicidal thoughts also. These recent deaths have produced a moment of clarity and fear in many: they don't want their loved ones, and even acquaintances, to suffer the same fate. Hence "I'm always ready to listen", "You're not alone", and the setting up of a series of suicide helplines. If this sounds like a dismissive description, in truth it is. I have personally been far down the dark road that these messages of solidarity seek to guide people out of. In my experience they achieve little even when people genuinely mean that a suicidal person can message them at odd times to pour out their souls—and, let's face it, very few people actually mean that. However, it is still a fundamentally positive reaction. More importantly, it is a necessary reaction. Even if some words prove ineffectual when it comes to the moment of truth, that people care enough to even express the sentiment can make all the difference in stopping someone's downward spiral.

"Despite the sense of alienation or worthlessness that at times instigates suicide—and there are many, many reasons why people kill themselves—only a vanishingly small number of people leave this world with no one who will miss them or need them.

What is problematic is the question of the suicide's courage.

Despite the sense of alienation or worthlessness that at times instigates suicide—and there are many, many reasons why people kill themselves—only a vanishingly small number of people leave this world with no one who will miss them or need them. There are parents who find themselves outliving their child. Siblings who lose a role model. Lovers who are left alone. People who fell out with them, who are left wondering if they were culpable. And there are responsibilities: co-workers who have to carry on without them, creditors who will never get what they were owed, people who counted on the person now gone. To think of the sum of people hurt, scarred or even inconvenienced by a suicide, we often judge harshly. We condemn. How selfish, no, to put one's misery over the pain of so many others? And so the word "coward" is thrown around.

Understand this: to call the dead cowardly is an act of disrespect. It is a valueless comment that only adds salt to the wound. They are gone beyond your criticism of their actions. Only those left behind will see your condemnation of someone important to them. Do you imagine that a father wants to be told that his dead son was a coward? That a daughter wants to know her parent took the easy way out? Perhaps you will say that you are speaking for them, that your harshness is motivated by your sympathy for their pain and loss. That is presumptuous. If you are one of the many, many people whose lives have been truly worsened by a suicide—if you are someone who really needed them to stay on in this world—you earn the right to insult. Call them whatever you desire. Most of us are not affected. We are bystanders in the peanut gallery. We must show respect in consideration of those bereaved. We must offer love and company where appropriate.

And for heaven's sake, be careful when accusing a potential suicide of cowardice. You don't want to add that ingredient of shame and self-loathing to an unpredictable and volatile cocktail. This is just as bad as the flipside, those who try to glorify and support the act of suicide itself. I have seen this. It's natural to try and sympathise with those who are gone, but sentiments such as "Suicide is the bravest thing you can do" do not help. Yes, the act requires a perfect loss of self-preservation, however momentary, and these are the traits our languages and cultures do glorify as "selflessness" and "bravery". But merely disregarding the value of your own life is not a commendable thing in itself. We cannot afford to romanticise this. Vulnerable people can be highly susceptible to influence.

These are tragedies that victimise more people than just the deceased. We must exercise discretion in what we say and to whom. To do otherwise invites consequences we may not be prepared to take responsibility for.

Zoheb Mashiur is an artist who graduated in economics from BRAC University, and is a columnist for SHOUT Magazine, The Daily Star.

E-mail: [email protected]

Comments