Responding to development challenges

Notable progress has been made on the development front, but important challenges remain and new challenges have emerged

Although Bangladesh was referred to as an “international basket case” and a “test case of development” during the 1970s and there was not much of progress during the 1980s to warrant a change in those descriptions, things started changing in the positive direction since the 1990s. Achievements on the economic and social fronts during the past two decades enabled the country to not only overcome those negative images but also to appear at the threshold of being an emerging economy. Inclusion of the country in the list of the next generation of emerging countries and in international credit rating, and acknowledgement of the country's achievement on the social side created a new sense of confidence and aspiration amongst the people of the country. Discussions started on the time frame for the country to get out of the not-so-distinguished club of least developed countries. All of the above, however, did not remove the challenges that the country continued to face. Formidable challenges were still there in terms of sustaining economic growth and raising it to a level needed for take-off as well as making it more inclusive.

As we started to prepare for saying good bye to 2013 and for welcoming 2014, the political situation of the country (which has always been marked by conflicts, and tension was brewing) came to a boiling point and a crisis situation arose. That, in turn, has created additional challenges of a short as well as medium term nature.

In addition to vulnerability to natural disasters, the country is now vulnerable to man-made crisis

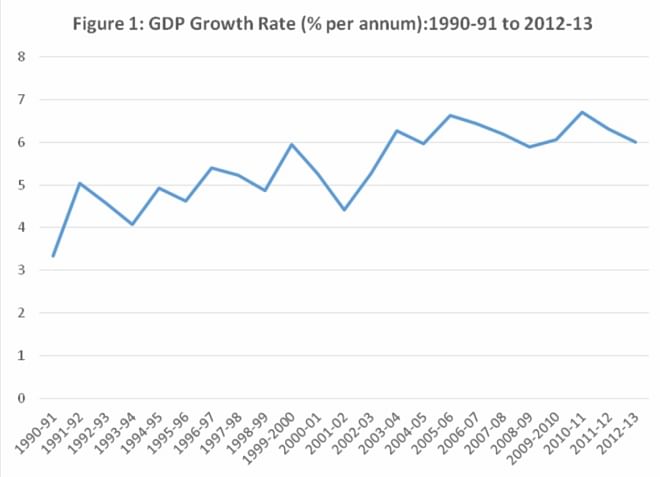

Bangladesh is known for its vulnerability to natural disasters like floods, droughts and cyclones. Over the years, the country of course developed a degree of capability to cope with the adverse effects of such crises. But the crisis of 2013-14 has been caused by political conflict; and despite the country's long history of such conflicts, the ability to cope with such crises remains limited. More importantly, this kind of crisis creates not just short term shocks but also medium term uncertainties that are inimical to investment and economic growth. The adverse effect of such uncertain environment on economic growth can be gauged from a comparison of GDP growth in Bangladesh during the pre-1991 and the post-1991 periods (1991 being the year of transition to “democracy”). Between 1970 and 1990, the average annual GDP growth remained below 4%, and it started to rise gradually since 1991.

Although there have been changes in the party in power during the two decades after that, there has been a good degree of stability in terms of economic and social policies. Apart from minor differences, the two major parties have maintained a policy of encouraging the private sector. On the social side also, there has been a degree of consistency in policies pursued, albeit with some differences in details. And that helped the country achieve notable results in the areas of education and health.

The adverse effects of uncertainty on the economy became clear during the transition of 2007-08 also when GDP growth fell below the 6% mark after a few years. Of course, it is difficult to isolate the effect of political uncertainty on economic growth. Moreover, during 2007-08, the economy of Bangladesh was affected by natural calamities as well as an external shock resulting from the global economic crisis. Anyway, it may be noted that (i) the political uncertainty of that period did create adverse effects on economic activities and on private investment decisions, and (ii) no decision was taken by the then interim government on major investment projects, especially in the field of infrastructure like power and roads.

During 2014, the country is again faced with a political crisis that is inflicting a shock on the economy, although there are important differences between the nature of the current shock and the earlier ones. The earlier crises were either short-duration in nature or the effects were limited to certain segments of the economy. For example, the uncertainty during the transition of 2007-08 mostly affected the formal sectors of the economy. Agriculture received special attention due to the adverse effect of natural calamities and the sharp rise in prices of food grains during the early part of 2008. On the other hand, the crisis of 2013-14 is affecting the entire economy. Moreover, the uncertainties surrounding the transition of 2013-14 started in the early part of 2013 and is in danger of being prolonged. An important question now is whether 2013-14 will be a “lost year”, and a major challenge before the country is to cope with the shock that is being inflicted by the political crisis and to bring back stability.

Development progress in Bangladesh is not a surprise: you reap as you sow

As mentioned already, Bangladesh has made notable progress in the area of economic and social development. Against the backdrop of descriptions like basket case and test case, the country is sometimes referred to as a case of “development surprise”. But if one looks carefully at what lies behind the story of the country's development progress, it will be clear that there is no surprise. The country has reaped the fruits of efforts made over more than two decades by its people and a broad cross-section of institutions.

In a nutshell, the success story of development in Bangladesh has the following broad elements: satisfactory performance of agriculture (with occasional dips due to natural calamities like floods and cyclones), a degree of industrialization (albeit partial) with impressive growth of labour intensive export oriented ready-made garment industry, a vibrant service sector, and international migration of labour serving as an alternative source of employment and foreign exchange. In all the above, the people's struggle for survival and their entrepreneurial ability combined with a conducive environment has played a key role.

Macroeconomic stability on the external front is provided by foreign exchange earned (mainly) through the export of RMG and remittances sent by those working abroad. On the domestic front, it has been possible to maintain fiscal balance mainly because of a cautious approach to spending combined with the government's inability to spend allocations under development budgets.

To put a little meat on the bones of the story provided above, look at agriculture first. Soon after the crop sector suffered a setback due to natural calamity in 2007, there was a very impressive turnaround in 2008. A combination of price incentive arising out of the sharp increases in the prices of food grains in the latter part of 2007 and early 2008 and incentives provided by the then Government contributed to this success. The present government has been able to ensure continuity to that success, and the country is now almost self-sufficient in food grains. That, in turn, has enabled the country to save the foreign exchange that would otherwise have been needed to import food grains.

A solvent agriculture provides the foundation for a vibrant rural economy by creating linkage effects for a variety of economic activities ranging from rural industries to trade and transport. With a reasonable extent of connectivity attained during earlier decades, the countryside of Bangladesh is well prepared to respond to the positive effects of satisfactory growth in agriculture.

In the manufacturing sector, while economic reforms and trade liberalization led to the decline of traditional industries like jute textiles, the country has seen the emergence of new industries like ready- made garments, pharmaceuticals, ceramics, etc. The success story of RMG is well known and provides a good example of how the private sector and entrepreneurs respond to the incentive structure that prevails in an economy. It must, however, be noted that the growth of this industry is based primarily on opportunities to earn profits at high rates due to a variety of incentives provided by the government and demonstrates how “primitive capital accumulation” can take place at the initial stages of industrialization through the exploitation of cheap labour. The darker side of the industry is reflected in poor working conditions, frequent hazards at work place as well as low wages, vulnerable terms of work, and absence of basic workers' rights in terms of freedom to form associations and bargain collectively.

The trade and service sector is quite heterogeneous, with some activities thriving from the linkage effects of the growing sectors like agriculture and industry and many others providing the poor people with merely a refuge where they can eke out a living. Levels pf productivity and returns naturally vary substantially between these various segments; but on the whole, growth of this sector forms an important part of the story of development success in Bangladesh.

Despite successes on various fronts mentioned above, employment remains a major weak link in the economy, and international migration acts an important source of jobs for many Bangladeshis. On that front as well,

the performance has varied a great deal, depending on a variety of factors like the country's image and the government's ability to negotiate deals with labour importing countries, management of the flow of workers, etc. While the years 2007, 2008 and 2012 showed good performance in this regard, 2013 has been a disappointing year. The flow of remittances reached US Dollars 23 billion in 2012, thus providing a major boost to the country's foreign exchange reserve.

On the social front, the first success, viz., a reduction in the rate of population growth, was attained even before the transition to democracy in 1991. That was followed by important achievements in areas like education, especially of girl children, and health. Successes in these areas may be ascribed to a combination of policies pursued by successive governments, e.g., free education up to high school, stipends for girl children, reforms in health sector, etc. and interventions by NGOs.

The brief outline of development success attained by Bangladesh during the past decades is basically meant to argue that sustained and untiring efforts of millions of people over several decades have yielded fruits that we see today and are being admired for. It may appear surprising in view of the daunting challenges at the initial stages and the bad start that the country had, but there is no real surprise in it.

There is no room for complacency: serious challenges lie ahead

However, the achievements mentioned above need to be strengthened and sustained for some more time in order for the country to really take off on a path of sustained development. And that's where major challenges lie. Starting with economic growth, it is clear that the country has remained stuck at a level of around 6% GDP growth per year. The economy's ability to sustain that in the face of shocks (be it from natural disasters, internal political crises or external factors like the global economic crisis) has been tested several times during the past decade or so, and every time the growth rate has slipped below that mark. Even during 2012-13, when the current political impasse started, growth rate declined to just 6% (see Figure 1). There is a tendency for policy makers to express satisfaction in this, citing the difficult global environment and dip in growth rates in other developing countries (e.g., India and China. But it needs to be remembered that Bangladesh is at a much lower level of development and average income compared to such countries; in order to narrow the gap with those countries and to reduce poverty at a faster rate, the country needs to grow at much higher rates than theirs. It simply cannot afford to falter on growth.

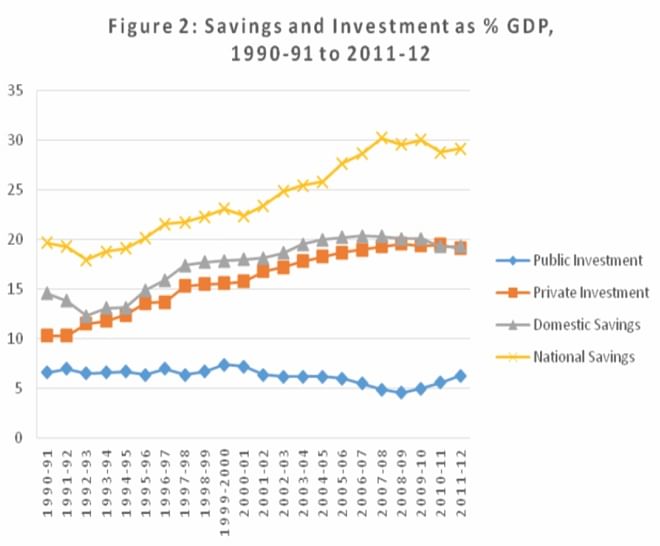

The mirror image of stagnation of GDP growth is found in the stagnation of investment rate (as % of GDP) around 24-25% (Figure 2). Several points are worth noting in this regard. First, overall investment as percentage of GDP increased from below 20% in the early 1990s to over 24% in 2003-04. But there has not been any significant improvement since then, and the figure crossed the 25% mark only in 2010-11. In recent years, the corresponding figures for China, India, and Vietnam have been around 45%, 35 %, and 35% respectively.

Second, private investment has stagnated in recent years, indicating a deterioration in the environment for such investment. Third, after years of decline in public investment there has been an increase since 2008-09. This is a welcome change from the point of view of development of infrastructure. But it should have happened in a way as to create a “crowding in” effect on private investment which has not been the case. In fact the state of infrastructure, especially of roads, is in a pathetic condition, and is not at all commensurate with an economy aspiring to graduate out of the club of LDCs.

Foreign direct investment is an area where the record of Bangladesh is very disappointing. The annual inflow has exceeded one billion US Dollars only in some years. In Vietnam, for example, the annual inflow exceeded US$14 billion in 2013 (which alone amounted to over 25% of GDP).

Pattern of growth is important and structural transformation is needed at a faster rate

From the point of view of moving an economy to a higher level of development and transferring its labour force from employment characterized low productivity and low incomes to those with higher productivity and incomes, structural transformation from agriculture to industry and eventually to services is important. There has been a degree of shift in the structure of the economy, but in terms of employment, the shift has been rather slow. If the historical experience of the developed countries and the recent experience of successful developing countries like the Republic of Korea and Malaysia are any guide, manufacturing industries have to play the role of the engine of growth at an early stage of economic growth. In Korea and Malaysia for example, at the early stages of their growth, growth of output in manufacturing has been double (or nearly so) that of overall GDP growth. This has not yet happened in Bangladesh. In fact, only in some years, growth of manufacturing has been more than one and a half times that of GDP growth.

Within manufacturing, labour intensive industries need to grow at high rates in order to absorb the surplus labour that is available in agriculture and other traditional sectors. In Bangladesh, this has happened to some extent through the growth of the RMG industry. And there is good potential for further growth at similar rates for some more time. But that will not be adequate to absorb all the surplus labour within a short period. This can be gauged from the fact that even after more than two decades of growth of the industry, there is no shortage of unskilled workers for ensuring its expansion at low wages. For transformation of the structure of employment at a faster rate, a few more labour intensive industries need to grow. Unfortunately that has not happened.

Apart from RMG, growth of other labour intensive industries with good growth potential (e.g., leather products, footwear, electronics, furniture, etc.) has not been anywhere near that of RMG. In fact, the share in total employment of an important industry like leather products has declined. This is so despite the demonstrated ability of Bangladeshi companies to export footwear to the global market. Quite clearly, there are features in the prevailing incentive structure of the economy that favour the growth of RMG industry much more than other industries in which the country has comparative advantage. This needs to be looked at carefully and corrective measures taken urgently.

In order to make economic growth more inclusive, the challenges of income inequality, productive employment and social protection will have to be addressed

From the point of view making economic growth truly inclusive, it would be necessary to address a number of challenges, including those of growing income inequality and of ensuring productive employment and decent work for all. Bangladesh is now a country of high income inequality, and concerted efforts are needed to reverse the trend. The present author has already written on this subject (in the 2013 annual supplement of the Daily Star), and the mechanisms and policy instruments that can be used to pursue this goal should not be unknown to policy makers. Non-adoption of such policies has to be taken as a lack of political will to address the challenge.

Likewise, the issue of productive employment and decent work has been in public discourse for a while, and policy measures are by now well known. For generating productive employment at a higher rate, a faster rate of structural transformation of the economy is essential _ a topic that has been discussed above. Several more industries like the garment industry are needed in order to provide productive employment to those who join the labour force every year (nearly two million per year) and those who need to move to jobs with higher productivity and incomes.

However, any job is not good enough. Recent experiences with

low wages, unacceptable working conditions and disasters at places of work in the RMG industry have already created an awareness about the importance of bringing about improvements in the quality of jobs. Absence of basic rights of workers is also an important issue. Serious commitment and appropriate action would be needed to pursue these goals.

Growth rate of productive employment within the country falls short of requirements, and international migration provides a major source of employment. Every year, the country needs to find about half a million jobs abroad for Bangladeshis. The number that has gone out with jobs has varied during the past few years. While 2012 was a good year with over 600,000 finding jobs abroad, 2013 has been a disappointing year, with the number plummeting to below 400,000 which is much less than what is required.

The pressure on the labour market is getting intensified with the worsening of the political crisis. While larger enterprises are threatening to lay off workers, the smaller ones (especially those who are self- employed) are finding it difficult to stay afloat.

One way of meeting the employment challenge (at least partially and in the short term) would be for the government to assume the role of the employer of last resort which in turn can be done through an employment guarantee programme. The latter was included in the present government's election manifesto through which it came to power in 2009. But since then, there has not been any real effort to fulfill that commitment.

Basic social protection floor needs to be created for all citizens

Every individual needs to have provision for old age, and should have protection against unemployment, sickness, child birth, and disability caused by accidents in work place, At the international level, there is a growing recognition of the importance of a “basic social floor” below which the poor and the vulnerable should not be allowed to slip. No country is so poor that it cannot afford to provide a basic social protection floor to its people. And certainly, for a country like Bangladesh that aspires to leave the club of least developed countries, it is time to give serious consideration to the building up of a “basic social floor” for its citizens.

From the point of view of accelerating the rate of poverty reduction on a sustained basis, it should be noted that a large segment of the population (many of whom may not be poor) in Bangladesh remain vulnerable to external shocks caused by natural calamities and economic crises of various types, e.g., sharp increases in food prices, economic downturns (which in turn may be due to external factors like the global economic crisis). To these have been added a man-made crisis through political conflict. Such shocks affect not only the poor; they often cause what is known as transient poverty _ non-poor people near the borderline falling into poverty. Measures of social protection can play an important role in tackling such transient poverty as well as in helping the poor.

There is of course a plethora of social protection measures (over 80 different programmes) in Bangladesh on which the country spends about 2.5% of its GDP every year. However, a careful look at them would show that most of them are minuscule programmes with limited coverage and small benefits. Many of them are designed with political goals. The government needs to understand that even from the point of view of electoral politics, a better strategy would be to adopt a more strategic approach of creating a basic social protection floor for all citizens (at least for the poor and the vulnerable) rather than appeasing small groups. And the budgetary implications of that may not be much more onerous than what is spent currently _ assuming that a bold decision can be taken to streamline and restructure the existing programmes.

More attention needs to be given to human capital formation

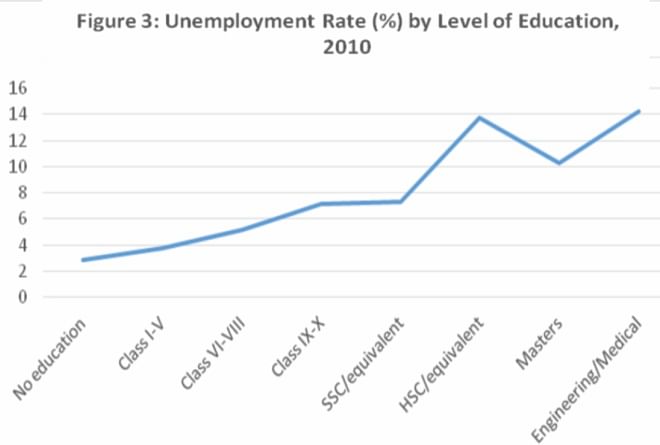

Labour is an important factor of production, but uneducated and unskilled labour is not of much help, especially as an economy moves to higher level of development. Investment in education and skill development plays an important role in that respect. Bangladesh has made the initial breakthrough in terms of enrolment (especially of girls) in primary education. But several challenges remain to be addressed. First, the quality of education is a major concern. Second, differences in quality between rural and urban areas and between schools of various types is also a critical issue. The issues relating to quality are important not only from the point of view of growth but also because of their implication for equity. Unless lower income people have access to good quality education, more education may accentuate the already high inequality.

As an economy experiences structural change, the types of education and skills that are required also change. For most jobs at the early stages of economic development (when traditional sectors like agriculture and simple manufacturing predominate), primary and secondary education may be adequate. For example, farmers with basic education may be able to adopt new technologies and farming methods. Likewise, for production workers in simple manufacturing like textiles and garment making, food processing, etc. primary or secondary education may be adequate for them to be able to undergo necessary skill training.

As for skills, in economies at early stages of development, most jobs involve routine manual work that require more of cognitive skills and less of thinking and creativity. But as an economy grows into higher levels of development, the proportion of jobs that require some thinking and higher level skills starts rising. As a result, the need for workers with post-secondary education and vocational and technical skills grows. The experiences of developed countries as well as those who have recently developed (e.g., Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan) corroborates this. Bangladesh must also take a long term view on this and prepare to meet its human capital needs at higher level of development.

However, simple expansion of higher education and general skill training may not be the answer to the challenge mentioned above. An important issue in this respect is the mismatch between education and skill offered by the education system and what is demanded in the labour market. That, in turn, results in unemployment of the educated (see Figure 3) _ a problem that is not limited to general education but also plagues technical and vocational education. Hence, planning higher education and skill training has to be approached with care.

The list of challenges is long, but return to stability is most urgent

For a country like Bangladesh, the list of challenges can be long. But the most important challenge at this time is to bring back political stability. It would not only be arrogant but also foolish to think that Bangladesh is no longer dependent on external assistance and hence can ignore the international environment. The country still needs external assistance and foreign direct investment, not least for large scale development projects and programmes. For exports and jobs abroad also, relations with the international community is critical.

The global economy and environment is tough and competitive. It took Bangladesh nearly two decades to come out of the basket case and test case images; and now it has quickly been included in the club of countries in crisis due to political conflict. We must get out of that soonest possible not only because of the stigma associated with such an image but also because it would be critical for pursuing our development agenda. Needless to mention, it will not be easy; and the starting point has to be the resolution of the current political crisis.

The author, an economist, is former Special Advisor, ILO, Geneva.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments