Anti-rumour campaign for Rohingyas

As aid workers rushed to vaccinate Rohingya refugees against measles earlier this year, rumours swirled through the overcrowded camps in Bangladesh - the injections would make women sterile and convert children into Christians.

The anecdote, included in an August report from the United Nations children's agency, UNICEF, illustrates how the refugees, who have fled Myanmar, are vulnerable to misinformation, "with little or no access to television, radio, or other media".

In response, humanitarians are trying innovative projects to counter rumours - translated as "flying news" in the Rohingya language - and to let refugees know how to access healthcare and bolster their shelters against storms, among other advice.

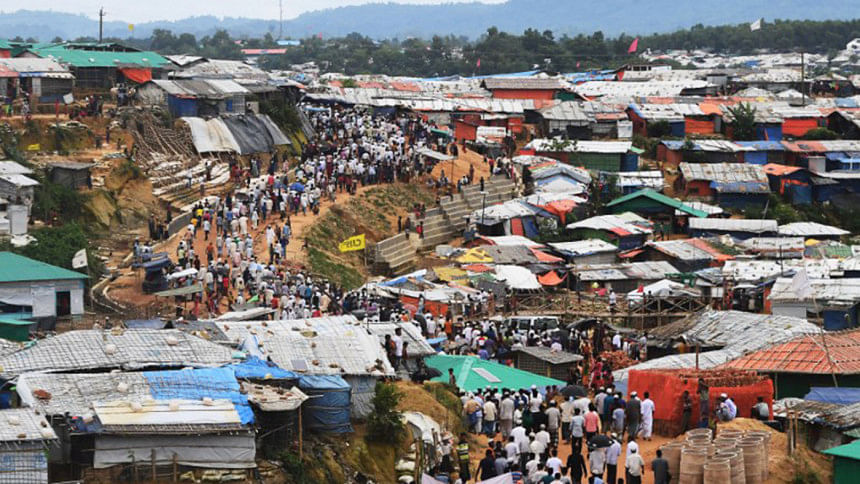

More than 900,000 Rohingya, an ethnic and religious Muslim minority in Myanmar, live in Bangladesh's Cox's Bazar district, the vast majority in camps, according to UNICEF.

About 700,000 of them arrived in the four months after deadly attacks by Rohingya insurgents on Myanmar security forces in August 2017, which were followed by military operations that the United Nations and rights groups said targeted civilians.

Myanmar has denied most of the allegations.

Aid agencies struggled to accommodate the influx of people, and a year on, the densely-populated camps remain vulnerable to storms that could strike during the cyclone season in October and November, bringing floods and disease.

"Life in the camps is hard and full of hazards," Fiona MacGregor, a spokeswoman for the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Cox's Bazar, said by email.

"In such circumstances, it is very easy for rumours and misinformation to spread - and it is vitally important people get timely, accurate information about everything from health issues to weather dangers."

Radio is a key tool for giving out that information, said MacGregor, especially as there is no formal written version of the Rohingya language.

But there are challenges, she added, as very few Rohingya used radios in their homeland across the border in Myanmar's Rakhine state.

The IOM is distributing 60,000 radios that can be powered with a hand crank, and is setting up "listening groups" in partnership with organisations including BBC Media Action.

'TENSION IS HIGH'

In the 300 or so groups of about 25 people each, one person leads discussions after listening to programmes that are usually stored on a memory stick, said Richard Lace, Bangladesh director for BBC Media Action.

The UK-based development charity coordinates with the Bangladesh state broadcaster to produce three shows a week, mostly offering practical information on issues like accessing services and preventing violence against women, said Lace.

BBC Media Action also works with a local station, Radio Naf, to produce two programmes a week, as well as a panel discussion each month with a live audience of about 75 people that focuses on topics affecting both refugees and local residents.

Past panels have tackled the perception that refugees are taking jobs and undercutting wages for day labour, and the mistaken impression their arrival has been accompanied by a big jump in drug smuggling and other crimes, Lace said.

"Tension is relatively high right now, so it's an interesting way to blow off steam," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by Skype from Cox's Bazar.

INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Information flows both ways, as aid agencies also receive feedback from refugees about their concerns via listening group sessions and surveys.

The international media development agency Internews produces the written "Flying News" bulletin, which helps alert aid workers to rumours in the camps as well as dispelling them.

A July bulletin, for example, tackled inaccurate information going around that rice and oil distributed to refugees had expired and was making them sick.

How to prevent human trafficking and extortion also featured, alongside contact details for trafficking hotlines run by the IOM and the UN refugee agency.

"You do not have to give money, sex or other favours in exchange for land, goods, food or services," the bulletin advised.

"Refugees have the right to complain about this, and should report incidents to the agency directly or to another agency they trust."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments