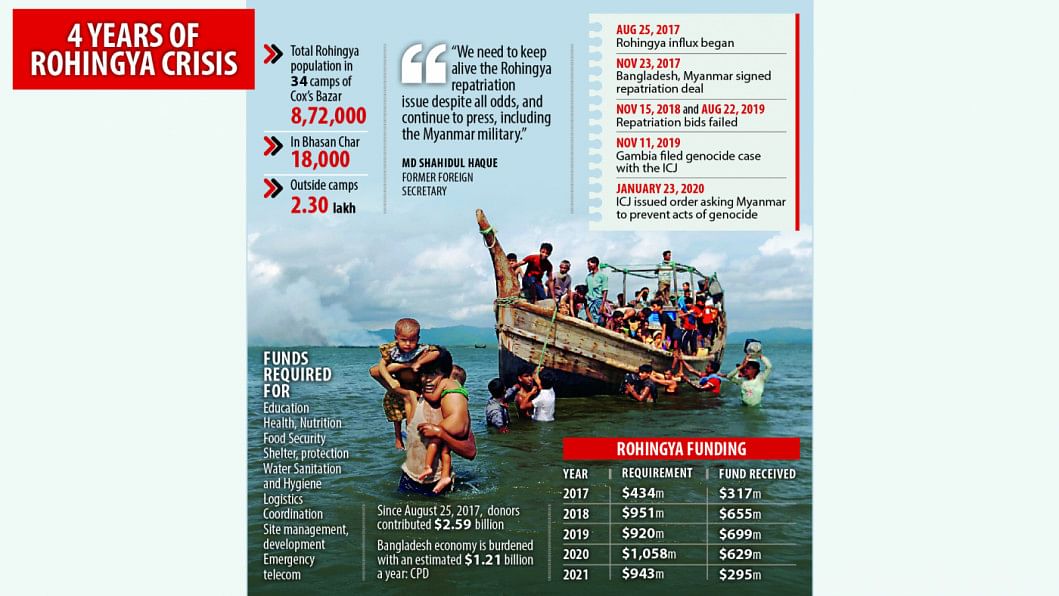

Nowhere to go

Rohingya repatriation has become even more uncertain following the military takeover in Myanmar while the displaced people find it riskier to go back to their motherland where there is no legitimate government right now.

"We need to keep alive the Rohingya repatriation issue despite all odds, and continue to press, including the Myanmar military."

To make things worse, the global focus has shifted to the Afghanistan crisis very recently with the Taliban seizing control of the South Asian country, analysts have said.

The Rohingyas, who had fled a brutal military crackdown since August 25, 2017, say there is no guarantee of citizenship, fundamental rights and safety in Myanmar at present.

"We do want to go back to Myanmar. That's our motherland. But there is no legitimate government there. So, who will take care of us? Who will take responsibility if we face a crackdown again?" said Khin Maung, coordinator of Free Rohingya Coalition in Bangladesh.

The Myanmar military, which seized power after overthrowing Aung San Suu Kyi's NLD-led government on February 1 this year, formed a caretaker government, but it has been largely criticised for killing over 1,000 civilians who demonstrated against the military coup.

On the other hand, the elected MPs of the National League of Democracy (NLD), representatives from different ethnic minority groups, including Karen, Kachin, Mon, Karenni, Chin, Kayan, and independent MPs, formed the National Unity Government (NUG) in hiding. It also formed an armed wing named "People's Defence Force" to launch a revolution against the military junta.

Fighting and killings in various parts of Myanmar are now a regular event. The NUG, however, is yet to make a headway in regaining control of the country. Meanwhile, representatives of neither of the sides are recognised at the UN -- a situation that is puzzling to the Rohingyas.

"The UN will fix which government is legitimate in October. So, everything is now fuzzy," said Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights Chairman Mohib Ullah from the Rohingya camp in Cox's Bazar.

Uncertainty over the repatriation is not new. Following the 2017 influx of about 750,000 Rohingyas, who joined about 300,000 others who had fled earlier waves of violence, Bangladesh government signed a repatriation deal with Myanmar.

Myanmar also signed a tripartite deal with UNHCR and UNDP on improving conditions in Rakhine State, home to majority of Rohingyas.

The meeting of Joint Working Group -- comprised of officials from Myanmar and Bangladesh -- has not taken place since May 2019 while two meetings are scheduled a year. Myanmar showed coronavirus pandemic as a reason for not holding the meetings and there has been no move at all after the military takeover, officials concerned said.

Even a trilateral initiative led by China involving Bangladesh and Myanmar could make no headway despite several meetings. Two repatriation attempts -- one on November 15 in 2018 and the second on August 22, 2019 -- fell flat.

A provisional order issued by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in January last year also failed to help make any progress.

SHIFT IN FOCUS

Foreign relations analysts and officials say the international communities -- especially of the Western powers -- have become more concerned about Myanmar's democracy than Rohingya repatriation.

In recent days, China, Russia and India, alongside the Western world, have become busy with Afghanistan crisis unfolding every day since the August 15 Taliban takeover that many say is leading to a serious instability and causing a refugee influx.

"After the military coup in Myanmar, the US and European countries have imposed some sanctions on military and businesses. However, they have not stopped doing business. On the other hand, Myanmar's engagement with China and Russia has increased, and this means Myanmar is on a strong footing," said M Humayun Kabir, president of Bangladesh Enterprise Institute (BEI).

Myanmar's military can be hurt if the Western countries stop importing from Myanmar, or Japan, India and ASEAN can put pressurise on them. That, however, is unlikely for now, he said.

Kabir, a former ambassador of Bangladesh, said the NUG has issued a statement saying it would amend laws to give citizenship and basic rights to the Rohingyas and ensure justice for the genocide, blaming the military for it. This goes in line with what Bangladesh wants.

Analysts said in the wake of the military coup, there has been some sympathy among the Myanmar's people for the Rohingyas. The issue, however, is dependent on the restoration of democracy led by the NUG.

Former foreign secretary Md Shahidul Haque also agrees and adds that Myanmar military has little interest in Rohingya repatriation, though they said they would honour the bilateral deals signed by the previous government.

WHAT'S NEXT?

Dhaka University International Relations Prof Dr Imtiaz Ahmed thinks that all the Rohingya repatriations in the past took place during the military regimes. Now, the military in power will be easier to be negotiated on Rohingya repatriation as they are under pressure domestically.

Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen also had spoken in similar line after the military takeover.

However, no effective communication has been made with the Myanmar military, officials say.

M Humayun Kabir and Md Shahidul Haque too think that theoretically this could be right that military government would be easier to be negotiated, but they say the ground reality is very different. Given the NUG's efforts to wage armed struggle, the military's main goal now is to consolidate power, not addressing Rohingya crisis, they say.

Md Shahidul Haque, also a senior fellow at the South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance (SIPG), North South University, added that Rohingya repatriation would now depend much on the restoration of democracy in Myanmar.

So, Bangladesh should consider establishing contacts informally with the NUG, which has in its policy incorporated granting citizenship and fundamental rights.

"We need to keep alive the Rohingya repatriation issue despite all odds and continue to press it upon, including with the Myanmar military," he said.

M Humayun Kabir said though ASEAN has not played any strong role in the past, it can still be useful in terms of addressing the crisis.

Some countries like Malaysia and Indonesia are quite vocal on the issue, and Dhaka needs to strengthen the engagement with them, he said.

Prof Imtiaz Ahmed said India and Japan have national interest in Myanmar but they should separate the Rohingya issue from it. "As Bangladesh's trusted allies, they should tell Myanmar to end the Rohingya crisis."

Prof Imtiaz further said the Rohingya voice globally has not been very strong as of now. There should be an initiative to create leadership and unity among the Rohingyas all over the world.

"Ultimately, the problem is between Myanmar and Rohingyas. We should facilitate their negotiating capacity," he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments