Inclusion, cultural integrity and land rights of the Indigenous Peoples in Asia

Shamsul Huda, Executive Director, ALRD

Solidarity and coordination among the indigenous peoples (IPs) in different countries of Asia are very important. In Bangladesh, about two percent of the population consists of IPs. Almost everywhere in the world, this community is facing various political, social, and economic challenges. But, in Bangladesh, there are some additional challenges due to the deliberate policy of denial of the existence of the IPs.

IPs have been living in Bangladesh for hundreds of years. Historically, they are part of the existence of Bangladesh. In recent years, certain agencies within the government are saying that Bangladesh does not have any IPs. At the same time, we are happy that the current government signed the historical Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord (CHT Accord) in the late nineties. The CHT Accord has been implemented partly but the issue related to land rights is yet to be addressed. We are facing numerous problems concerning the IPs residing in the hills and plains. There is systemic discrimination and indifference of the administration.

The current pandemic has aggravated the sufferings of the IPs in terms of food security and availability of healthcare services. Their needs mostly go unaddressed, ignored, or denied. The objective of this roundtable discussion is to learn from each other through the sharing of experiences and come up with some action plans to move forward towards land rights and human rights for the IPs across Asia and the world.

Gam A. Shimray, Secretary-General, Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP)

The global environmental crisis calls for urgent action to prevent the collapse of biodiversity across the planet. Governments, organisations, and conservationists have put forward proposals for bringing 30 percent and up to 50 percent of the planet's terrestrial areas under formal protection and conservation regimes by 2030 and 2050 respectively, to address the biodiversity and climate change crisis. However, the danger with such ambitious global targets is that they are often used against IPs and local communities as a justification for taking away their lands, territories, and resources. Globally, it has been estimated that up to 136 million people were displaced in protecting half of the currently protected areas which make up 8.5 million square kilometres.

A recent study released by the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), shows that a transformative human rights-based conservation method offers a way forward. The study shows that up to 1.87 billion people live in the world's most critical conservation areas. If these people gain ownership rights to their lands and if the governments become protectors of their rights to reside in those territories, there would be no need to take these lands into state ownership.

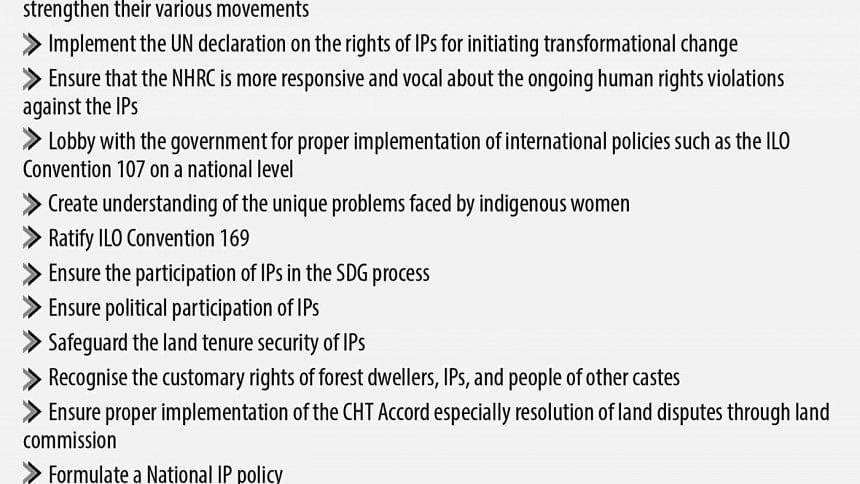

It is imperative that the United Nations (UN) declaration on the rights of IPs is enacted by governments to initiate transformational change. After all, Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change. As the world has begun to recognise the significance of indigenous leadership, we appeal to the people of Bangladesh to join the community in Asia in initiating the turning point for transformational change for the common growth of all.

Pallab Chakma, Executive Director, Kapaeeng Foundation

In Bangladesh, only 50 indigenous communities are formally recognised by the government. 13 of these communities reside in CHT and more than 40 in the plains. It is estimated that more than three million IPs live in Bangladesh.

Various state and non-state actors participate in evicting IPs from their lands in the name of building forest reserves, national parks, tourism sites, and many others. The non-state actors occupying indigenous lands include political elites, influential individuals, or corporate/business groups. IPs have fought time and again in response to these forced evictions. During such protests, they become subjected to further violence.

The various development projects such as the Modhupur Eco Park Project in 1966 or the Sajek Tourism Complex created in 2012, forcefully evicted the IPs from their traditional lands without proper compensations.

Overall, there seems to be a culture of impunity surrounding the human rights violations against the indigenous community and criminalisation of the rights defenders seems to be the trend. There is also a shrinking democratic space for rights activists. Currently, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is not vocal enough about the ongoing human rights violations. This needs to change.

We want to ensure and protect the land rights of the IPs and we want to live with dignity in our own country.

Professor Dr. Sadeka Halim,

Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

We still do not have clear statistics about the actual number of IPs in the country. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), approximately 1.8 percent of the total households in the country consist of IPs.

In CHT, hard-core poverty rate among IPs is 36 percent and in the plains the rate is 25 percent. Whereas, the national rate for hard-core poverty is 18 percent.

In our constitution, customary land rights of the IPs are not recognised. But, the government has amended the constitution although it still does not give fundamental rights to the IPs.

The major cause of displacement in CHT is the forest department's development projects used as a strategy to acquire the lands of the IPs.

Bangladesh is signatory to International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 107 but there is no implementation of such international policies at the national level. We need to lobby with the government to implement these policies effectively.

Democratic spaces and civil society are no longer that vocal in establishing the fundamental rights of the IPs and protesting the violence occurring against indigenous women. We cannot lump indigenous women's issues with mainstream women's issues. We must look into the unique problems faced by indigenous women. For instance, when indigenous women get raped, they have issues reporting to the police or communicating with the doctor because they cannot speak Bangla properly.

Mai Thin Yumon,

Asia Focal Person, Global Indigenous Youth Caucus

Even though the IPs comprise only five percent of the world's population, we protect 80 percent of the planet's biodiversity. This is a result of the historical stewardship of the IPs in the sustainable management of land and forest resources. There has been increasing recognition of land rights of IP so that they can contribute their knowledge to find solutions to the world's problems. However, the IPs continue to be marginalised in many countries, resulting in discriminatory policies and legislation, especially when it comes to land and access to natural resources. Part of this legislation which has had dire consequences for their livelihood and socio-cultural practices is directly connected to environmental protection, biodiversity conservation, and climate action. For IPs, land is not just a source of food and income but also cultural identity.

Many Asian countries have criminalised IPs' traditional practices. Policy instruments seeking to mitigate climate change tend to be developed in a hurry, with zero to minimal participation from IP. Mitigation actions such as renewable energy projects can cause displacement and violation of IPs' rights when the projects do not comply with international rights standards such as ILO Convention 169. Even though legal frameworks exist, implementation is incredibly weak or non-existent. IPs' land is often perceived as "empty" or "unused" by the state in countries like Laos, Malaysia and Myanmar. Measures to engage youth in protecting our land need to be innovative and the narratives around traditional farming need to change.

Mayfereen Ryntathiang, President, Grassroots, Shillong, India

In India, the word "indigenous" is alien to the government. Unfortunately, we are still being called "tribals" or "scheduled tribes." In Meghalaya, we are very much indigenous in terms of our land ownership, identity, and self-determination. The ongoing development work on indigenous land is usually done without the consent of the IP since none of these communities has ever consented to give up their land and forests to corporates. Now that we are aware of how much of our indigenous rights are violated, it is time to fight back. We have the intellectual tools needed to reclaim our dignity, lands, and resources.

The human rights knowledge that the state of India and the UN hold is not being passed on to the indigenous communities. India has agreed to most of the UN's policies regarding indigenous rights, but there is no implementation. The government should look into how many UN documents they have signed but not acted upon. We also need to acknowledge that there are written or unwritten cultural laws that protect our knowledge, land, and people. These customary laws should be approved as the immediate state laws for IPs. These laws have protected 70 percent of the natural biodiversity of the state of Meghalaya.

Sanjeeb Drong, General Secretary, Bangladesh IP Forum

The main issue is the denial of the identity as IPs in the constitution, law, and many government documents. There are a few exceptions. The majority of IPs in Bangladesh live in the plain lands. However, there are no laws in the government mechanism for the plain land IPs. There exists only one law for them, called the State Acquisition and Tenancy Act. The seventh five-year plan at least included indigenous issues and promised to implement the UN declaration of the rights of IPs in Bangladesh. The plan also committed to ratifying the ILO Convention 169. The government committed to forming a new land commission for plain land IPs in 2008, but nothing has been implemented.

The government has major publications on sustainable development goal implementation, yet IPs are fully excluded from this implementation. The participation of IPs' organisations in the SDG process is the most important.

We should have a national policy for IPs in Bangladesh. Political participation of IPs should be ensured. IPs and IPs' organisations should be actors in their own development, and their capacity should be built for this.

Shankar Limbu, Secretary-General, Lawyers Association for Human Rights of Nepalese Indigenous peoples (LAHURNIP), Nepal

Acquiring land rights is the prime agenda of the IPs because land rights are fundamental. Regardless of the country, we have lost our territories and our ancestral domain. We don't have political power and are considered second-class citizens. Every decision made by the political actors overlooks and adversely affects our land rights. The government still applies the principle of eminent domain when it comes to land. The principle of eminent domain applies to the development process mainly to dispossess the IPs' land territories and natural resources. The primary effect is that we are losing our identity, culture, the customary land tenure system, and spiritual values. This means our existence is under threat.

We can rectify the political issues through self-government and self-rule, which is quite common in indigenous communities. How do we correct doctrines which are against IPs? IPs have a pre-existing, customary right which cannot be overturned by subsequent state policy. The IPs' permanent sovereignty over land territories and natural resources, which has been recognised by customary law and practices, is stronger than state law, and we must stick to it. Another critical factor is self-determination in development. Development processes must be sustainable for IPs.

Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is a way to negotiate and bring forward our land rights. International financial institutions like World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and European Investment Bank have safeguard policies on IP's rights, and they recognise FPIC of the peoples if they invest in indigenous territories.

Professor Dr Meghna Guha Thakurta,

Advisor, International CHT Commission, Bangladesh

Jhum cultivation is being entrenched by mainstream discourses, especially in CHT. Jhum cultivation also existed in the plain lands, in the Garo community, but it was almost erased. It still exists in a small scale thanks to the 1900 manual which has protected the land. However, the manual has been amended many times to make jhum cultivation marginal, even in CHT. There are many indigenous techniques which are beneficial to all of us in this regard. Jhum cultivators have shared that jhum cultivation leads to the land becoming scarce and so sufficient production for the entire year is not possible for the growing population. Therefore, they need supplementary activities.

Many development plans have been created in CHT for orchard farming, but the orchards are run by the state or UN bodies because they claim that IPs do not have the capacity to run these orchards. So, the UN bodies or state become the managers of the orchards while the IPs become the labourers. The IPs only demand a small piece of land where they can carry out cultivation and regrow the forests they are losing. In CHT, many women's livelihoods depend on producing textiles. They previously used dyes from their own trees to dye the clothes, but these trees are disappearing since nobody is replanting them. The women are losing their livelihoods due to this loss of ecology.

Signe Leth, Senior Advisor, Indigenous Women & Land Rights, Asia, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA)

To IPs, land and natural resources are not just commodities, but part of their identity, spirituality, and life. IPs must be included in decisions affecting their lives, their territories, and natural resources. Not only is it a need, but a right that must be respected.

On the contrary, IPs are being criminalised, harassed, and even killed for attempting to protect their land and territories. The global rush for economic growth has led to an increased demand for land and natural resources, with IPs' land being a primary target for illicit accusations. With countries looking to cushion economic recession after COVID-19, this tendency is only increasing. The land-grabbing is driven by several forces, including mega development projects, extractive industries, logging, agribusiness, green-energy projects, and large-scale conservation activities. IPs' territories are also invaded by settlers and other dominant groups, migrant communities, or armed groups. The land-grabbing and invasion lead to mass forced evictions of IPs from their traditional lands and territories, and numerous forms of other gross human rights abuses, violations, and conflicts. The invasion and grabbing of IPs' lands are accelerated by the fact that many IPs suffer from weak legal protection of their community lands and, therefore, are vulnerable to land-grabbing and the associated human rights violations. Safeguarding the land tenure security of IPs is critical for their future and is one of the fundamental rights and demands of the global indigenous movement.

Barrister Raja Devasish Roy, Chakma Chief and Former Member (Vice-Chairperson), United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

The issue with the tripartite relationship of governments, trade unions, and employers' associations is that the trade unions have been bullied into not supporting the indigenous cause. How can we have a convention if the tripartite bodies that run ILO cannot look at the committee of expert reports and recommendations and try to push it in the conferences of the International Labour Conference?

We are following a European pre-colonialist model of the legal system currently. There are good examples of land laws, such as the Indian 2013 Land Acquisition Act which recognises FPIC and the Forest Rights Act of India, 2006. Bangladesh and other countries can learn from these legislations where customary rights of forest dwellers, IPs, and people of other castes are recognised.

Self-determination is a part of the right of people to freely determine their political status and pursue their economic, social, and cultural development. FPIC, in a way, is an expression of self-determination. The UN recognises that IPs have something to contribute to environmental and sustainable development. On a parallel level, we have the convention of biological diversity that has opened up for signing and ratification.

Shamsuddoza Sajen,

Commercial Supplements Editor, The Daily Star & Moderator of the session

25 percent of the world's surface is owned, occupied, or used by IPs and they are the custodian of 80 percent of the world's diversity. However, they account for 15 percent of the total extreme poor in the world and in Asia, the average poverty of the IP is three times higher than the Asian average. A major contributing factor for this is a lack of land rights. In many countries, their land rights are not given formal recognition. We believe that strong political will recognising their rights to their ancestral lands can protect the community along with protecting the entire civilisation from the adverse effects of climate change.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments