Accelerating gender-inclusive urban WASH: A call for action

In collaboration with The Daily Star, WaterAid organised a roundtable on March 11, 2025, titled 'Accelerating Gender-Inclusive Urban WASH: A Call for Action.' The roundtable aimed to bring together experts, practitioners, and stakeholders to discuss the challenges and proposed solutions for gender-inclusive WASH in Dhaka. Below is a summary of the discussion and the key outcomes.

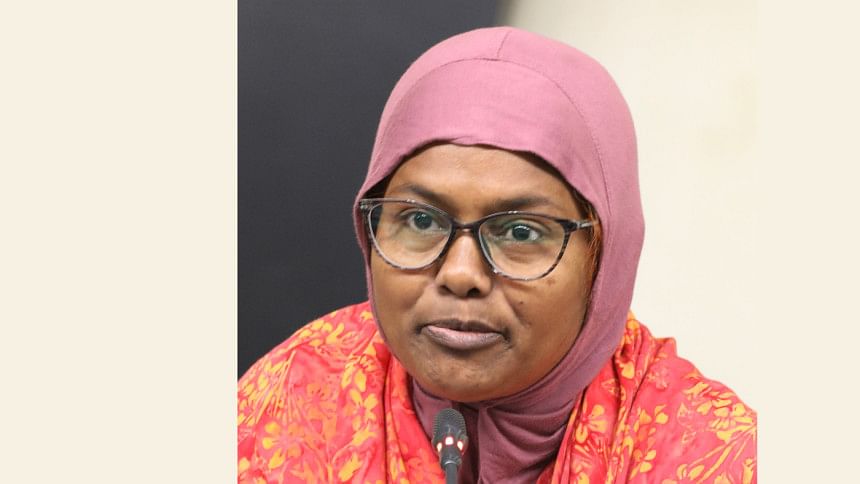

Hasin Jahan, Country Director, WaterAid Bangladesh (Keynote Presentation)

The situation of Dhaka's WASH facilities is dire, especially for vulnerable groups. Consider the plight of flower sellers, beggars, female traffic police officers, or female construction workers who spend 10–12 hours outside daily. How do they access WASH facilities? And what about the 300,000 street vendors in Dhaka who need clean water and toilets while serving food? These pressing concerns demand immediate attention.

The city sees approximately 400,000 daily commuters, while over four million LIC dwellers live in 5,000 LICs—half of them women. Yet, there are only 641 public toilets, with just 116 managed by the city corporation. Some areas have water ATMs, but access remains insufficient. While Dhaka WASA supplies legal water connections to these areas through its Low-Income Community (LIC) unit for community-based organisations (CBOs) formed by LIC dwellers, there is no systematic toilet infrastructure. NGOs attempt to fill this gap, but coverage remains limited to 400–500 LICs, even with joint efforts.

To tackle this issue, we, a group of experts and practitioners, are developing a set of planning principles for an action plan to ensure WASH facilities in public spaces and low-income communities (LICs) for RAJUK. We initiated a WASH plan for Ward 20, Zone 3, of the Dhaka North City Corporation, which includes Sattala LIC. Despite having 18 public toilets and two WASA water ATMs, only six toilets are functional. Our analysis revealed that 13 toilets would be sufficient, yet 18 exist in ineffective locations. Since six toilets are already functional, we need seven new ones to address this. However, restoring all 18 toilets could be a practical solution. With limited government resources and tax constraints, optimising their use is crucial for maximum impact.

To achieve this, we recommend that city corporations adopt four key steps. First, they should set minimum standards for public WASH facilities, ensuring they are clean, functional, safe and accessible. Second, implementing a management model with tariffs and a safety net for low-income users would help sustain operations while maintaining affordability. Existing models by WaterAid and Bhumijo provide successful examples of efficient operation and maintenance, ensuring proper management that can be replicated.

Public engagement is not just crucial, it's a game-changer. Introducing a user rating system for lease renewals, focusing mainly on women's feedback, would encourage better service quality and accountability among facility operators. Lastly, utilising existing spaces, such as mosques and fuel stations, to develop gender-inclusive toilet facilities under proper management would create safe and accessible sanitation options for all users.

We propose several key initiatives that have the potential to significantly transform the WASH situation in Dhaka. By installing water ATMs in LICs, we can provide residents with reliable access to clean water, reducing dependency on unsafe sources. Creating a low-cost blue-pink toilet model for both men and women would ensure safe sanitation, particularly for women and girls, while also serving as an alternative to open bathing. Lastly, encouraging corporate investment in sanitation infrastructure could significantly improve living conditions in LICs while enhancing corporate branding. These initiatives offer a beacon of hope for a better future.

A unified strategy among all authorities and institutions is not just important; it's crucial. Additionally, interim WASH solutions should be ensured for LIC dwellers until long-term housing plans are implemented. Ward 20 can serve as a scalable model, demonstrating that only through coordinated efforts can clean water and sanitation be established as universal rights.

Recommendations from the presentation:

- Set minimum standards for public WASH facilities, including those in markets, fuel stations, mosques, and other public spaces, to ensure they are clean, functional, safe, and accessible.

- Implement a management model with tariffs and a safety net for low-income users to sustain operations and maintenance while retaining affordability.

- Introduce a user rating system for lease renewals of public toilets, prioritising women's and other marginalised people's feedback to improve service quality and accountability among facility operators.

- Utilise existing spaces such as markets, mosques and fuel stations to develop gender-inclusive toilet facilities under proper management, ensuring wider accessibility.

- Expand access to water in LICs by installing water ATMs. This will provide residents with a reliable and affordable supply, reducing dependency on unsafe sources.

- Encourage corporate investment in sanitation infrastructure to improve living conditions in LICs and enhance corporate social responsibility and brand image.

- Ensure coordination among institutions by aligning RAJUK's DAP and Dhaka WASA's master plan while implementing interim WASH solutions for LIC dwellers until long-term housing plans are in place.

Farhana Rashid, Chief Executive Officer, Bhumijo

When Bhumijo began working on public sanitation in 2016, we approached the Nur Mansion section of Gawsia Market, a women-centric space. We proposed to the market committee that we renovate and manage an existing toilet, choosing Gawsia for its significance to women.

Despite data showing 40 female salespersons and up to 400,000 female visitors daily during Eid, the committee initially claimed that no women used the facilities. After negotiations, we were given 15 days for renovation and another 15 days for operation. If no women use the facility, we will restore it to its original state. Within months, the same committee requested upgrades for the men's toilets.

Policymakers must take sanitation seriously. Government institutions often resist opening facilities to the public. Additionally, we are not just service providers—we are deeply committed to a customer-centric approach. At the same time, we prioritise affordability and leverage digital collaboration to enhance accessibility and efficiency. Those of us on the ground will continue pushing for change, but policymakers must engage to make public sanitation genuinely inclusive.

Shamim Ara Shammi, Programme Manager, Operations, Ultra-Poor Graduation Programme, BRAC

Over the past three months, a recurring issue in urban LIC community meetings has been the frequent damage of water and sanitation lines. As a result, residents often receive contaminated water instead of safe drinking water. Last month, I visited a LIC behind Pangu Hospital, which houses around 400 households. The water there had a foul odour, and many residents suffered from diarrhoea and other diseases.

Essential services are often taken for granted, but LIC residents—who sell vegetables, work in homes, and provide critical services—are deprived of basic needs. LICs exist within affluent areas like Banani and Dhanmondi, yet their residents remain invisible in policy and infrastructure planning. Our policies, infrastructure strategies, and review mechanisms must be more practical and inclusive.

Alauddin Ahmed, Project Manager, International Training Network at Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology (ITN-BUET)

In Bangladesh, 18% of women fetch water, compared to only 4-5% of men, highlighting an apparent gender disparity. Similarly, sanitation responsibilities disproportionately fall on women, who are also concentrated in lower-paying sanitation jobs, while higher-paid roles remain male-dominated.

True gender inclusivity means equal decision-making and access to resources. Yet, how often are women consulted when designing sanitation facilities? Their voices remain secondary at both institutional and household levels. Without addressing these disparities, discussions on gender-friendly policies remain empty promises.

Gender safety in WASH has two key dimensions: technological aspects such as functional toilet locks and broader community WASH initiatives. Sustainable and inclusive solutions require active involvement from all stakeholders.

Falguni Tripura, Member, Bangladesh Adivasi Forum

Urban sanitation challenges in Dhaka and beyond must address accessibility for marginalised communities, including indigenous women, transgender individuals, and hijra communities. In the Chittagong Hill Tracts, water scarcity worsens due to climate change, and inadequate school facilities often force young girls to skip school during menstruation. Poor housing designs further fail to consider hygiene needs.

Public sanitation remains inaccessible mainly to marginalised groups, such as disabled women and street vendors, who struggle to find WASH facilities. Beyond access, the lack of proper sanitation leads to violence—many indigenous women face assault simply while trying to use a toilet. This is not just a policy failure but a failure of social justice.

Fatema Begum, General Secretary, Nagar Daridra Basteebashir Unnayan Sangstha (NDBUS)

During menstruation, inadequate sanitation exacerbates the situation, with makeshift toilets offering no privacy, exposing women to further danger. Teenage girls are often forced to bathe in semi-open spaces, making them vulnerable to harassment or worse. Victims are usually blamed, while perpetrators evade accountability.

As a representative of the Korail LIC, I am committed to securing legal water access for disadvantaged groups. With 80% of the poor suffering from waterborne diseases, we need well-planned, sustained strategies to address these challenges.

Salma Mahbub, General Secretary & Executive Director, Bangladesh Society for the Change and Advocacy Nexus (B-SCAN)

Since 2009, we have worked to improve sanitation facilities in key locations such as the National Museum, Dhaka University, and Mirpur Cricket Stadium. Since 2011, our collaboration with WaterAid has prioritised accessibility in public toilets, yet the broader issue remains largely unaddressed. Many public toilets fail to meet the needs of disabled individuals, despite policies mandating universal accessibility.

Inconsistent standards across authorities and a lack of enforcement further hinder progress. Authorities and NGOs must involve us early to ensure public toilets are accessible. The Ministry of Social Welfare and other relevant ministries should also lead in this area.

Md. Fazlul Hoque, Deputy Chief Executive Officer, Sajida Foundation

City corporations are responsible for sanitation, yet there is no clear accountability when restaurants, fuel stations, or workplaces fail to provide usable toilets. Although the High Court recently ruled that individuals must receive at least 7.5 litres of water daily in emergencies, enforcement remains challenging.

Financial institutions can play a role by incorporating sanitation compliance into financing agreements for entrepreneurs, especially in the restaurant and street food sectors. Ensuring access to sanitation requires urgent, multi-sector collaboration. Our microfinance institution (MFI) focuses on inclusive WASH, with plans to bring at least 1,000 restaurants into the sanitation programme for sustained hygiene and public health improvements.

Partha Shankar Saha, Assistant News Editor, Prothom Alo

When we discuss urban issues, our focus is often disproportionately centred on Dhaka. However, new cities are emerging across Bangladesh. Are we considering sanitation and hygiene challenges in these newly developing urban centres?

From a media perspective, I have noticed that discussions on gender-inclusive sanitation tend to peak around specific occasions, such as International Women's Day or World Water Day. Why do we only highlight these problems on special days? Do people not need clean water and sanitation every day? This raises a significant concern.

Mostafizur Rahman, National Programme Officer - Climate and Environment, Embassy of Sweden

The term 'accelerating' implies that we need to intensify our efforts. However, we need to examine the existing gaps before focusing on acceleration. The fact that we still have to advocate for these basic facilities demonstrates that gender and inclusivity are not yet embedded in urban planning.

Water and sanitation are not just women's issues—they affect everyone. WaterAid conducted a study revealing that women face significant harassment and violence when trying to access WASH facilities. Yet, these concerns are consistently overlooked. When sanitation facilities are designed, little thought is given to whether they will be genuinely accessible. We continue to design facilities without fully considering the diverse needs of all users.

We must assess whether existing policies truly serve everyone and require a fundamental shift in mindset. Gender inclusivity cannot be an isolated discussion—it must be part of a broader, more holistic approach to urban planning and public service design.

Meaningful private sector engagement depends on recognising how WASH aligns with business models. We are committed to reviewing existing laws and ensuring proper budget allocation to support this mission.

Sumaiya T. Ahmed, Head of Sustainability, PRAN-RFL Group

The private sector can tailor market policies to address fundamental challenges by analysing local needs. We seek your input to understand the situation on the ground. We continuously invest in innovation, keeping consumers at the centre.

We are eager to collaborate with WASH and hygiene projects to drive meaningful impact. Achieving more requires collaboration, not individual effort, and I commit to being a partner in developing innovative, gender-inclusive WASH facilities.

Peter Maes, Chief of WASH, UNICEF Bangladesh

It is crucial to recognise that one-third of children in urban LICs lack access to a proper water supply, and half do not have adequate sanitation facilities. Children living in LICs face a 30% higher health risk than their peers.

These issues are deeply interconnected—when a child contracts diseases like diarrhoea, their nutritional intake suffers, leading to stunted growth and impaired cognitive development. This, in turn, affects their education, future economic prospects, and, ultimately, the nation's overall development.

Additionally, poor WASH conditions contribute to anxiety, stress, and increased risks of gender-based violence. Young girls are particularly vulnerable, as many toilets lack menstrual hygiene facilities, making it difficult for them to attend school regularly. Studies have shown that improving WASH infrastructure can reduce school absenteeism by up to 15%, which is a significant impact.

Md. Manir Hossain, Additional Director (Deputy Secretary), Department of Women Affairs, Ministry of Women and Children Affairs (MoWCA)

The Department of Women's Affairs, operating under MoWCA, is key in providing programmes and facilities for women nationwide. The draft action plan for WASH, currently focused on Dhaka's two city corporations, should be expanded to all city corporations and pourashavas.

Public sanitation facilities are inadequate, and expanding them requires public-private collaboration. Infrastructure development alone is not enough; participation from local governments, city corporations, and stakeholders is essential, ideally through public-private partnerships.

Partha Hefaz Shaikh, Director – Programmes and Policy Advocacy, WaterAid Bangladesh

In 2003, we launched a sanitation movement. After that, the government and local authorities took ownership of the programme, engaging with NGOs and the private sector. While NGOs and private entities are still involved, ensuring that the government leads the programme with strong political will and prioritises awareness is crucial.

The government must actively participate as a key player in executing these programmes in coordination with the local government institutions. At the same time, NGOs and the private sector should also contribute significantly to accelerating gender-inclusive urban WASH initiatives. We must reconsider how to make community engagement more meaningful and effective.

Dr. Mohammed Helal Uddin, Executive Vice Chairman, Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA)

In Dhaka, rickshaw pullers and other disadvantaged groups lack access to proper toilets, highlighting a significant gap in development efforts. Similar challenges extend beyond the two city corporations to poverty-stricken areas nationwide.

Beyond WASH, women's safety remains a critical concern. Introducing facilities such as ATM-style water dispensers and community bathing spaces for women, managed by the community with private sector support, could improve access, hygiene, and income generation.

We must adopt innovative strategies to ensure the safety of women and children accessing WASH facilities. Regarding financing, our Microfinance Institution (MFI) window has the potential to offer subsidised loans for this purpose. However, despite the availability of funds, investments in WASH remain limited due to a lack of clear policy direction.

Upon receiving initial reports from MFIs, I thoroughly assess the necessary funding and its intended use before granting final approval. I am committed to approving funding requests for WASH facilities, provided that MFIs submit formal proposals. Therefore, the demand must come from the MFIs to facilitate resource allocation for WASH.

Rasheda K. Chowdhury, Charge of Coordination, CSO Alliance

The issue of WASH facilities must be continuously advocated as the current situation remains unsatisfactory, despite the efforts of numerous organisations over the years. WASH is not just a gender issue but a fundamental development priority.

Several successful models of inclusive WASH exist in Dhaka and should be replicated in all LIC areas. We need robust, evidence-based data to guide policy to achieve sustainable solutions. I urge ITN-BUET to provide scientific research on this issue. Additionally, collaborative efforts must be leveraged to scale up these solutions.

Due to the vulnerability and mobility of LIC dwellers, many initiatives fail to reach their full potential. Influential platforms like The Daily Star can play a crucial role by highlighting and disseminating stories of successful WASH models. Like stories of a village boy excelling in cricket inspire people, similar narratives about effective WASH models in LICs could create a widespread impact. Social media and e-papers offer tremendous potential to amplify these stories.

Shireen Pervin Huq, Chief, Women's Affairs Reform Commission

The WASH programme must extend beyond urban centres to suburban areas. In cities like Dhaka, RAJUK should mandate that public buildings make their toilet facilities accessible to everyone. Gonoshasthaya Nagar Hospital, a non-profit institution, provides toilet facilities for nearby traffic police on its first floor. Under its management, the hospital built two public toilets, setting an example for profit-driven hospitals, particularly in Dhanmondi and other urban centres. These institutions should be required to adopt similar gender-inclusive WASH initiatives to benefit urban communities.

Beyond sanitation, access to clean water must also be a priority. In Gulshan, I observed a household placing jars and mugs outside their home for rickshaw pullers and passersby to drink from—a simple yet impactful initiative that should be replicated in other areas.

City Corporations and other authorities, especially RAJUK and WASA, must adopt a practical, results-driven approach to urban planning and WASH solutions. These authorities must make commitments and ensure these commitments translate into tangible initiatives, directly improving the living conditions of residents, particularly in underserved communities.

Tanjim Ferdous, In-Charge, NGO & Foreign Missions, Business Development Team, The Daily Star (Moderator)

Despite progress, women and marginalised groups face barriers. Gender-sensitive WASH solutions improve health, dignity, and economic opportunities, requiring collaboration, innovation, and strong policies to ensure inclusive, accessible, and sustainable services for all.

Recommendations

- Implement gender sensitive and inclusive WASH programmes with genuine political commitment by integrating sanitation into national policies and practices.

- Enforce mandatory public access to sanitation facilities in all public buildings, hospitals, markets and other spaces, ensuring they provide and manage well-maintained, accessible toilets for everyone.

- Implement gender-sensitive infrastructure, including separate, safe and well-maintained toilets in public spaces, to ensure women's safety and health security in sanitation facilities.

- Increase women's and marginalised groups' representation in decision-making and leadership roles to create inclusive and effective policies, particularly in the WASH sector.

- Ensure sanitation for marginalised communities by addressing the needs of disabled individuals, indigenous communities and transgender people in WASH planning and infrastructure.

- Prioritise affordability and utilise digital collaboration to enhance WASH access and service efficiency. Invest in space-efficient innovations like basement toilets to address congestion in urban areas.

- Scale up successful inclusive WASH models from Dhaka to all LIC areas, adapting them to local needs for broader accessibility and impact.

Enact necessary policy and legal reforms to establish WASH as a fundamental right and hold authorities accountable for its provision and accessibility.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments